Paris - La Belle Époque

- Past Imperfect -PLBE- Paris - 1933 -PLBE- Paris

Contents

- 1 Quote

- 2 Paris during the Belle Époque

- 3 Appearance

- 4 City Device

- 5 Climate

- 6 Demonym

- 7 Economy

- 8 Geography

- 9 Population

- 10 Arenas

- 11 Attractions

- 12 Bars and Clubs

- 13 Cemeteries

- 14 City Government

- 15 Crime

- 16 Citizens of the City

- 17 Corax of Paris

- 18 Current Events

- 19 Fortifications

- 20 Galleries

- 21 Gallû of Paris

- 22 Holy Ground

- 23 Hospitals

- 24 Hotels & Hostels

- 25 Landmarks

- 26 Law Enforcement

- 27 Lupines of Paris

- 28 Mages of Paris

- 29 Mass Media

- 30 Monuments

- 31 Museums

- 32 Parks

- 33 Private Residences

- 34 Restaurants

- 35 Ruins

- 36 Schools

- 37 Shopping

- 38 Telecommunications

- 39 Theaters

- 40 Transportation

- 41 Vampires of the City

- 42 Websites

Quote

In Paris, everybody wants to be an actor; nobody is content to be a spectator. -- Jean Cocteau

Paris during the Belle Époque

In Short

Paris in the Belle Époque, between 1871 and 1914, from the beginning of the Third French Republic until the First World War, saw the construction of the Eiffel Tower, the Paris Métro, the completion of the Paris Opera, and the beginning of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on Montmartre. Three universal expositions in 1878, 1889 and 1900 brought millions of visitors to Paris to see the latest in commerce, art and technology. Paris was the scene of the first public projection of a motion picture, and the birthplace of the Ballets Russes, Impressionism and Modern Art.

The expression Belle Époque came into use after the First World War, a nostalgic term for what seemed a simpler time of optimism, elegance and progress.

Paris 1900: La Belle Époque, l'Exposition Universelle, l'Art Nouveau (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8MZGusqwKPo)

Rebuilding after the Commune

After the violent end of the Paris Commune in May 1871, the city was governed by martial law, under the strict surveillance of the national government. The government and parliament did not return to the city from Versailles until 1879, though the Senate returned earlier to its home in the Luxembourg Palace.

The end of the Commune also left the city's population deeply divided. Gustave Flaubert described the atmosphere in the city in early June 1871: "One half of the population of Paris wants to strangle the other half, and the other half has the same idea; you can read it in the eyes of people passing by." But that sentiment soon became secondary to the need to reconstruct the buildings that had been destroyed in the last days of the Commune. The Communards had burned the Hôtel de Ville (including all the city archives), the Tuileries Palace, the Palais de Justice, the Prefecture of Police, the Ministry of Finances, the Cour des Comptes, the State Council building at the Palais-Royal, and many others. Several streets, particularly the rue de Rivoli, had also been badly damaged by the fighting. The column in Place Vendôme had been toppled, on a suggestion from Gustave Courbet, a supporter of the Commune. On top of the reconstruction, the new government was obliged to pay 210 million francs in gold to the victorious German Empire as reparations for the disastrous Franco-Prussian War of 1870. On August 4, 1871, at the first meeting of the city council after the Commune, the new Prefect of the Seine, Léon Say, put forward a plan to borrow 350 million francs for reconstruction and to pay Germany. The city's bankers and businessmen quickly raised the money, and the reconstruction was soon underway.

The Conseil d'État and Palais de la Légion d'Honneur (Hôtel de Salm) were rebuilt in their original style. The new Hôtel de Ville was given a more picturesque Renaissance style than the original, borrowed from the Château de Chambord in the Loire Valley, with a facade decorated with statues of outstanding personages who contributed to the history and fame of Paris. The destroyed Ministry of Finance on the rue de Rivoli was replaced by a grand hotel, while the Ministry moved into the Richelieu wing of the Louvre, where it remained until 1989. The ruined Cour des Comptes on the left bank was replaced by the gare d'Orléans, also known under the name gare d'Orsay, now the Museé d'Orsay. The one difficult decision was the Tuileries Palace; built in the 16th century by Marie de' Medici, a royal and imperial residence. The interior had been entirely destroyed by the fire, but the walls were still largely intact, and remained standing for ten years, while the fate of the ruins was debated. Baron Haussmann, in retirement, appealed for a restoration of the building as an historic monument, and it was proposed to turn it into a new museum of modern art. But, in 1881, the new Chamber of Deputies, more sympathetic to the Commune than previous governments, decided that it was too much a symbol of the monarchy, and had the walls pulled down.

On 23 July 1873, the National Assembly endorsed the project of building a basilica at the site where the uprising of the Paris Commune had begun; it was intended to atone for the sufferings of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune. The Basilica of Sacré-Cœur was built in the neo-Byzantine style, and paid for by public subscription. It was not finished until 1919, and quickly became one of the most recognizable landmarks in Paris.

The Parisians

The population of Paris was 1,851,792 in 1872, at the beginning the Belle Époque. By 1911, it reached 2,888,107, higher than today's (2015) population. At the end of the Second Empire and the beginning of the Belle Époque, between 1866 and 1872, the population of Paris grew only 1.5 percent. The population surged by 14.09 percent between 1876 and 1881, then slowed down again to 3.3 percent between 1881 and 1886. After that it grew very slowly until the end of the Belle Époque, reaching its historic high of almost three million persons in 1921, before beginning a long decline until the early 21st century.

In 1886, about one-third of the population of Paris (35.7 percent) had been born in Paris. More than half 56.3 percent) had been born in other departments of France, and about eight-percent outside France. In 1891, Paris was the most cosmopolitan of European capital cities, with seventy-five foreign-born residents for every thousand inhabitants, compared with twenty-four for Saint-Petersburg, twenty-two for London and Vienna, and eleven for Berlin. The largest communities of immigrants were Belgians, Germans, Italians and Swiss, with between twenty and twenty-eight thousand persons from each country, followed by about ten thousand from Great Britain and equal number from Russia; eight thousand from Luxembourg; six thousand South Americans; and five thousand Austrians. There were 445 Africans, 439 Danes, 328 Portuguese and 298 Norwegians. Certain nationalities were concentrated in specific professions; Italians in the businesses of making ceramics, shoes, sugar and conserves; Germans in leather-working, brewing, baking and charcuterie. The Swiss and Germans were predominant in businesses making watches and clocks, and also accounted for a large proportion of the domestic servants.

The remnants of old Paris aristocracy and the new aristocracy of bankers, financiers and entrepreneurs mostly had their residences in the 8th arrondissement, from the Champs-Élysées to the Madeleine), in the quartier de l'Europe and butte Chaillot; the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, the quartier Saint-Georges, from rue Vivienne and the Palais-Royal to Roule and the plain of Monceau. On the right bank, they lived in Le Marais; on the left bank, on the south of the Latin quarter, at N(Notre-Dame-des-Champs and Odéon; near Les Invalides and at the École Militaire. The less affluent shop owners lived from porte Saint-Denis to Les Halles, to the west of boulevard de Sébastopol. The middle class employees of enterprises, small businesses and government lived closer to the center, along the Grands boulevards, in the 10th arrondissement, in the 1st and 2nd arrondissements near the Bourse (Stock Exchange), in the Sentier quarter near Les Halles, and in Le Marais.

Under Napoleon III, Haussmann had demolished the poorest, most crowded and historical neighborhoods in the center of the city to make room for the new boulevards and squares. The working-class Parisians had moved out of the center toward the edges of the city; particularly to Belleville and Ménilmontant in the east, to Clignancourt and Grandes Carrières to the north, and on the left bank to the area around the Gare d'Austerlitz, Javel and Grenelle, usually to neighborhoods that were close to their places of work. Small quarters of working-class Parisians still remained in the center of the city, on the sides of the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève in the Latin Quarter, near the Sorbonne and the Jardin des Plantes, and along the covered Bièvre River, where the tanneries had been located for centuries.

Paris was both the richest and poorest city in France. Twenty-four percent of the wealth in France was found in the Seine department, but fifty-five percent of burials of Parisians were made in the section for those unable to pay. In 1878, two-thirds of Parisians paid less than 300 francs a year for their lodging, a very small amount at the time. An 1882 study of Parisians, based on funeral costs, concluded that twenty-seven percent of Parisians were upper or middle class, while seventy-three percent were poor or indigent. Incomes varied greatly according to the neighborhood: in the 8th arrondissement, there were eight poor persons for ten upper or middle class residents; in the 13th, 19th and 20th arrondissements, there were seven or eight poor for every well-off resident.

The Political Scene

The French national government concluded, after the Commune, that Paris was too important to be run by the Parisians alone; on April 14, 1871, just before the end of the Commune, the National Assembly, meeting in Versailles, passed a new law giving Paris a special status different from other French cities, and subordinate to the national government. All male Parisians could vote. The city was given a municipal council of eighty members, four from each arrondissement, for a term of three years. The council could meet for four sessions a year, none longer than ten days, except when considering the budget, when six weeks were allowed. There was no elected mayor. The real powers in the city remained the Prefect of the Seine and the Prefect of Police, both appointed by the national government.

The first legislative elections after the Commune, on January 7, 1872, were won by the conservative candidates; Victor Hugo, running as an independent candidate on the side of the radical republicans, was soundly defeated. However, the radical Republicans dominated the Paris municipal elections of 1878, winning 75 of the 80 municipal council seats. In 1879, they changed the name of many of the Paris streets and squares; Place du Château-d’Eau became Place de la République, and a statue of the Republic was placed in the center in 1883. The avenues de la Reine-Hortense, Joséphine and Roi-de-Rome were renamed Hoche, Marceau and Kléber, after generals of Napoleon I.

The burning of the Tuileries Palace by the Commune meant there was no longer a residence for the French head of state. The Élysée Palace was chosen as the new residence in 1873. It had been built between 1718 and 1722 by the architect Armand-Claude Mollet for Louis Henri de La Tour d'Auvergne, comte d'Évreux, then had been purchased in 1753 by Lous XV for his mistress, the Marquise de Pompadour. During the Consulate, it was owned by Joachim Murat, one of Napoleon's marshals. In 1805, Napoleon made it one of his imperial residences, and it became the official presidential residence when his nephew, Louis-Napoléon, future emperor, became President of the Second Republic, and remained so to this day. During the Bourbon Restoration the Élysée gardens were a popular amusement park. The Élysée palace had no large room for ceremonial events, so a large ballroom was added during Third Republic.

The most memorable Parisian civic event during the period was the funeral of Victor Hugo in 1885. Hundreds of thousands of Parisians lined the Champs Élysées to see the passage of his coffin. The Arc de Triomphe was draped in black. The remains of the writer were placed in the Panthéon, formerly the Church of Saint-Geneviève, which had been turned into a mausoleum for great Frenchmen during the Revolution of 1789, then turned back into a church in April 1816, during the Bourbon Restoration. After several changes during the 19th century, it was secularized again in 1885 on the occasion of Victor Hugo's funeral.

Social Unrest

The Belle Époque was spared the violent uprisings which had brought down two French regimes in the 19th century, but it had its share of political and social conflict and occasional violence. Labor unions and strikes had been legalized during the regime of Napoleon III. The first labor union congress in Paris took place in October 1876, and the socialist party had recruited many members among the Paris workers. On May 1, 1890, the socialists organized the first and unauthorized celebration of May Day, the international day of labor, leading to confrontations between police and demonstrators.

The majority of political violence came from the anarchist movement of the 1890s. The first attack was organized by an anarchist named Ravachol who set off bombs at three residences of wealthy Parisians. On April 25, he set off a bomb at the restaurant Véry at the Palais-Royal, and was arrested. On November 8, anarchists planted a bomb in the office of the Compagnie Minière et Métallurgique, a mining company, on the Avenue de l'Opéra. The police found the bomb, but when it was taken to the police headquarters it exploded, killing six persons. On December 6, an anarchist named Auguste Vaillant set off a bomb in the building of the National Assembly, wounding forty-six persons. On February 12, 1894, an anarchist named Émile Henry set off a bomb at the café of the Hôtel Terminus next to the Gare Saint-Lazare, killing one person and wounding seventy-nine.

Another political crisis shook Paris beginning on December 2, 1887, when the President of the Republic, Jules Grévy, was forced to resign when it was discovered that he had been selling the nation's highest award, the Légion d'honneur. A popular general, Georges Ernest Boulanger, had his name put forward as a potential new leader. He became known as "the man on horseback" because of images of him on his black horse. He was supported by ardent nationalists, who wanted a war with Germany to take back Alsace and Lorraine, lost in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War. Monarchist politicians began to promote Boulanger as a potential new leader, who could dissolve the parliament, become President, bring back the lost provinces and restore the French monarchy. Boulanger was elected to parliament in 1888, and his followers urged him to go to the Élysée Palace and declare himself president; but he refused, saying that he could win the office legally in a few months. The wave of enthusiasm for Boulanger quickly faded away, he went into voluntary exile, and the government of the Third Republic remained firmly in place.

Dreyfus Affair: An Introduction

The Dreyfus Affair (French: l'affaire Dreyfus, pronounced: [la.fɛʁ dʁɛ.fys]) was a political scandal that divided the Third French Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. The affair is often seen as a modern and universal symbol of injustice, and it remains one of the most notable examples of a complex miscarriage of justice. The major role played by the press and public opinion proved influential in the lasting social conflict.

The scandal began in December 1894, with the treason conviction of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian and Jewish descent. Sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly communicating French military secrets to the German Embassy in Paris, Dreyfus was imprisoned on Devil's Island in French Guiana, where he spent nearly five years.

Evidence came to light in 1896 — primarily through an investigation instigated by Georges Picquart, head of counter-espionage — identifying a French Army major named Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy as the real culprit. After high-ranking military officials suppressed the new evidence, a military court unanimously acquitted Esterhazy after a trial lasting only two days. The Army then accused Dreyfus with additional charges based on falsified documents. Word of the military court's framing of Dreyfus and of an attempted cover-up began to spread, chiefly owing to "J'accuse", a vehement open letter published in a Paris newspaper in January 1898 by famed writer Émile Zola. Activists put pressure on the government to reopen the case.

In 1899, Dreyfus was returned to France for another trial. The intense political and judicial scandal that ensued divided French society between those who supported Dreyfus (now called "Dreyfusards"), such as Sarah Bernhardt, Anatole France, Henri Poincaré and Georges Clemenceau, and those who condemned him (the anti-Dreyfusards), such as Édouard Drumont, the director and publisher of the antisemitic newspaper La Libre Parole. The new trial resulted in another conviction and a 10-year sentence, but Dreyfus was given a pardon and set free.

Eventually all the accusations against Dreyfus were demonstrated to be baseless. In 1906 Dreyfus was exonerated and reinstated as a major in the French Army. He served during the whole of World War I, ending his service with the rank of lieutenant-colonel. He died in 1935.

The affair from 1894 to 1906 divided France deeply and lastingly into two opposing camps: the pro-Army, mostly Catholic "anti-Dreyfusards" and the anticlerical, pro-republican Dreyfusards. It embittered French politics and encouraged radicalization.

Captain Alfred Dreyfus' grandchildren donated over three thousand documents to the Musée d'art et d'histoire du judaïsme (Museum of Jewish art and history), including personal letters, photographs of the trial, legal documents, writings by Dreyfus during his time in prison, personal family photographs, and his officer stripes that were ripped out as a symbol of treason. The museum created an online platform in 2006 dedicated to the Dreyfus Affair, giving the public access to these exceptional documents.

Appearance

[[]]

City Device

Climate

Paris has a typical Western European oceanic climate which is affected by the North Atlantic Current. The overall climate throughout the year is mild and moderately wet. Summer days are usually moderately warm and pleasant with average temperatures hovering between 15 and 25 °C (59 and 77 °F), and a fair amount of sunshine. Each year, however, there are a few days where the temperature rises above 30 °C (86 °F). Some years have even witnessed some long periods of harsh summer weather, such as the heat wave of 2003 where temperatures exceeded 30 °C (86 °F) for weeks, surged up to 39 °C (102 °F) on some days and seldom cooled down at night. More recently, the average temperature for July 2011 was 17.6 °C (63.7 °F), with an average minimum temperature of 12.9 °C (55.2 °F) and an average maximum temperature of 23.7 °C (74.7 °F).

Spring and autumn have, on average, mild days and fresh nights, but are changing and unstable. Surprisingly warm or cool weather occurs frequently in both seasons. In winter, sunshine is scarce; days are cold but generally above freezing with temperatures around 7 °C (45 °F). Light night frosts are however quite common, but the temperature will dip below −5 °C (23 °F) for only a few days a year. Snowfall is uncommon, but the city sometimes sees light snow or flurries with or without accumulation.

Rain falls throughout the year. Average annual precipitation is 652 mm (25.7 in) with light rainfall fairly distributed throughout the year. The highest recorded temperature is 40.4 °C (104.7 °F) on July 28, 1948, and the lowest is a −23.9 °C (−11.0 °F) on December 10, 1879.

Demonym

Parisian

Economy

Geography

Paris is located in northern central France. By road it is 450 kilometres (280 mi) south-east of London, 287 kilometres (178 mi) south of Calais, 305 kilometres (190 mi) south-west of Brussels, 774 kilometres (481 mi) north of Marseilles, 385 kilometres (239 mi) north-east of Nantes, and 135 kilometres (84 mi) south-east of Rouen. Paris is located in the north-bending arc of the river Seine, spread widely on both banks of the river, and includes two inhabited islands, the Île Saint-Louis and the larger Île de la Cité, which forms the oldest part of the city. The river’s mouth on the English Channel (La Manche) is about 233 mi (375 km) downstream of the city. Overall, the city is relatively flat, and the lowest point is 35 m (115 ft) above sea level. Paris has several prominent hills, of which the highest is Montmartre at 130 m (427 ft). Montmartre gained its name from the martyrdom of Saint Denis, first bishop of Paris atop the "Mons Martyrum" (Martyr's mound) in 250 A.D.

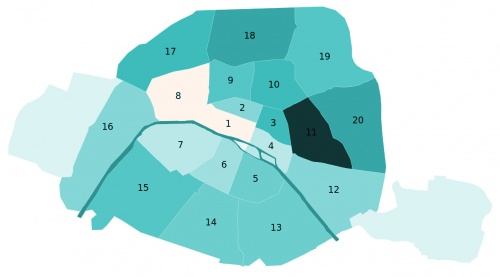

Excluding the outlying parks of Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes, Paris occupies an oval measuring about 87 km2 (34 sq mi) in area, enclosed by the 35 km (22 mi) ring road, the Boulevard Périphérique. The city's last major annexation of outlying territories in 1860 not only gave it its modern form but also created the twenty clockwise-spiralling arrondissements (municipal boroughs). From the 1860 area of 78 km2 (30 sq mi), the city limits were expanded marginally to 86.9 km2 (33.6 sq mi) in the 1920s. In 1929, the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes forest parks were officially annexed to the city, bringing its area to about 105 km2 (41 sq mi). The metropolitan area of the city is 2,300 km2 (890 sq mi).

Arrondissements

Introduction

The city of Paris is divided into twenty arrondissements municipaux, administrative districts, more simply referred to as arrondissements. These are not to be confused with departmental arrondissements, which subdivide the 101 French départements. The word "arrondissement", when applied to Paris, refers almost always to the municipal arrondissements listed below. The number of the arrondissement is indicated by the last two digits in most Parisian postal codes (75001 up to 75020).

Population

- -- City (2,714,068) - 1901 census

- -- Urban (4,000,000) - 1905 census

Arenas

Attractions

- -- Casino de Paris -- The Casino located at 16, rue de Clichy, in the 9th arrondissement, is one of the well known music halls of Paris, with a history dating back to the 18th century. Contrary to what the name might suggest, it is a performance venue, not a gambling house.

Bars and Clubs

Cemeteries

City Government

Crime

The Apaches of Paris

[[]]

Apaches was a term that was introduced by Paris newspapers in 1902 for young Parisians who engaged in petty crime and sometimes fought each other or the police. They usually lived in Belleville and Charonne. Their activities were described in lurid terms by the popular press, and they were blamed for all varieties of crime in the city. In September 1907, the newspaper Le Gaulois described an Apache as "the man who lives on the margin of society, ready to do anything, except to take a regular job, the miserable who breaks in a doorway, or stabs a passer-by for nothing, just for pleasure.

Citizens of the City

Corax of Paris

Current Events

Fortifications

Galleries

Gallû of Paris

Cleaners

Vultures

Holy Ground

Religion and the Secular Society

Paris in the Belle Époque saw a long and sometimes bitter dispute between the Catholic Church and governments of the Third Republic. During the Commune, the Church had been particularly targeted for attack; 24 priests and the Archbishop of Paris had been taken hostages and were shot by firing squads in the final days of the Commune. The new government after 1871 was conservative and Catholic, and, through the Ministère des Cultes, provided substantial funding for the Church establishment, and approved the building (without government funds) of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on Montmartre as an act of expiation for the events of 1870-1871. The anti-clerical Republicans took power in 1879, and one of their leaders, Jules Ferry, declared: "My objective is to organize humanity without God and without kings." In March 1880, the Assembly outlawed religious congregations not authorized by the State, and on 30 June had the police expel the Jesuits from their building at 33 rue de Sèvres. 260 monasteries and convents were closed in Paris and the rest of France. A new law was passed declaring that all public education should be non-religious (laïque) and obligatory. In 1883, new laws were passed forbidding public prayers, and forbidding soldiers to attend religious services in uniform. In 1881, twenty-seven cadets from the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr (Military Academy of Saint-Cyr) were expelled for attending a mass at church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The law against working on Sunday was repealed in 1880 (it was reinstated in 1906 to assure workers a day of rest), and in 1885 divorce was authorized.

The new Municipal Council of Paris, also dominated by radical republicans, had little formal power, but it took many symbolic measures against the Church. Nuns and other religious figures were forbidden to have official positions in hospitals, statues were put up to honor Voltaire and Diderot, and the Panthéon was secularized in 1885 to receive the remains of Victor Hugo. Several of the streets of Paris were renamed for republican and socialist heroes, including Auguste Comte (1885), François-Vincent Raspail (1887 ); Armand Barbès (1882); and Louis Blanc (1885). Specifically forbidden by the Catholic Church, cremation was authorized at the Père Lachaise cemetery. In 1899, the Dreyfus Affair divided Parisians (and the whole of France) even more; the Catholic newspaper La Croix published virulent anti-Semitic articles against the army officer.

The new National Assembly of 1901 had a strongly anti-clerical majority. At the urging of the socialist members, the Assembly officially voted the separation of Church and State on December 9, 1905. The budget of 35 million francs a year given to the Church was cut off, and disputes took place over the official residences of the clergy. On December 17, the police evicted the Archbishop of Paris from his official residence at 127 rue de Grenelle; the Church responded by banning midnight masses in the city. A law of 1907 finally resolved the issue of property; churches built before that date, including the cathedral of Notre Dame, became the property of the French state, while the Catholic Church was given the right to use them for religious purposes. Despite the cutoff of government assistance, the Catholic Church was able to build 24 new churches, including 15 in the suburbs of Paris between 1906 and 1914. Official relations between Church and State were almost non-existent to the end of the Belle Époque.

The Jewish community in Paris had grown from 500 in 1789, or one percent of the Jewish community in France, to 30,000 in 1869, or 40 percent. Beginning in 1881, there were new waves of immigration from Eastern Europe, bringing 7 to 9,000 new arrivals each year, and French-born Jews in the 3rd and 4th arrondissements were soon outnumbered by new arrivals, whose numbers increased from 16 percent of the population in those arrondissements to 61 percent. The pogroms in the Russian Empire between 1905 and 1914 provoked a new wave of immigrants arriving in Paris. The community faced a strong current of antisemitism, exemplified by the Dreyfus Affair. With the arrival of the great number of Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe and Russia, the Paris community became more and more secular and less religious.

There was no mosque in Paris until after the First World War. In 1920, the National Assembly voted to honor the memory of the estimated one hundred thousand Muslims from the French colonies in the Maghreb and black Africa who died for France during the war, and gave a credit of 500,000 francs to build the Grand Mosque of Paris.

Hospitals

Hotels & Hostels

Landmarks

Law Enforcement

The Paris police force was completely re-organized after the fall of Napoleon III and the Commune; the sergents de ville were replaced by the 'Gardiens de la paix publique (Guardians of the Public Peace), which by June 1871 had 7,756 men, under the authority of the Prefect of Police, named by the national government. Following a series of anarchist bombings in 1892, the number was increased to 7,000 guardians, 950 sous-brigadiers and 80 brigadiers. In 1901, under the prefect Louis Lépine, in order to keep up with the technology of the time, a unit of policemen on bicycles (called the hirondelles after the brand of the bicycles), was formed, numbering 18 per arrondissement, and reaching 600 by 1906 for the whole city. A unit of river police, the Brigade fluviale, was organized in 1900 for the Universal Exposition, as well as a unit of traffic police, who wore a symbol of a Roman chariot embroidered on the sleeve of their uniform. The first six motorcycle policemen appeared on the streets in 1906.

In addition to the Gardiens de la paix publique (Gardiens de la paix, for short), Paris was guarded by the Garde républicaine (Republican Guard), under the military command of the Gendarmerie nationale. Gendarmes had been a particular target of the Commune; 33 had been taken hostages and were executed by a (Communard) firing squad on rue Haxo on May 23, 1871, in the last days of the Commune. In June 1871, they provided security in the damaged city. They numbered 6,500 men in two regiments, plus a unit of cavalry and a dozen cannon. The number was reduced in 1873 to 4,000 men in a single regiment, called the Légion de la Garde républicaine (Legion of the Republican Guard), with its headquarters on the quai de Bourbon, and the troops quartered in several barracks around the city. The Republican Guard was given the duty of providing security for the President of the Republic at the Élysée Palace, the National Assembly and the Senate, at the prefecture of police, and also at the Opéra, theaters, public balls, racetracks, and other public places. A unit of bicyclists was formed on June 6, 1907. When World War I began, the entire unit of Paris gendarmes was mobilized and fought at the front during war; 222 of them lost their lives.

By a decree of 29 June 1912, to assure the sûreté (security) of Paris by fighting organized crime (Apaches, bande à Bonnot), a criminal section called the Brigade criminelle was created.

Lupines of Paris

Bone Gnawers

Get of Fenris

Glass Walkers

Shadow Lords

Mages of Paris

Technocracy

Tradition

Celestial Chorus

Cult of Ecstasy

Electrodyne Engineers

Order of Hermes

Verbena

Mass Media

- Le Petit Journal

- Le Jounal

- Le Petit Parisian

- Le Matin

Monuments

Museums

Parks

Private Residences

Restaurants

Ruins

Schools

Shopping

Telecommunications

Theaters

Transportation

Vampires of the City

The Legacy of Villon: The Edicts

"The Edicts are written in English for understanding, and in French for mood purpose."

L'Art / The Art

Vous ne devrez ni voler, ni détruire, ni altérer un Objet d'Art sans l'Autorisation de l'Ancien parmi les Anciens. Aucun

Objet d'Art ne doit sortir du Territoire de France sans l'Autorisation de l'Ancien parmi les Anciens.

You must not steal, destroy, or alter an Object of Art without the Authorization of the Eldest among you.

No Object of Art is to exit the domain of France without the Authorization of the Eldest among you.

L'Elysée / The Elysium

Les Lieux protégé par l'Elysée ne pourront être le théatre de violence, ni de la Chasse. Provoquer la violence ou Chasser

dans l'Elysée sans l'Autorisation de l'Ancien parmi les Anciens est passible d'une Chasse de Sang. Par mesure de sécurité,

l'accès de certains Elysées sera réglementé.

Grounds protected by the Elysium will not be sullied by violence of hunt. Provoke violence or hunting in an Elysium

without the authorization of the Eldest among you can be punished by the Blood Hunt. For security reasons, the access to

some Elysiums will be limited.

L'Ordre / Order

L'ordre doit être garanti par le Prince, qui s'approprie donc de manière exclusive les moyens d'assurer

l'ordre et le bien-être de la Famille comme du Bétail. Il est par consécquent formellement interdit d'influencer

les forces de polices et les forces armées.

Les Masques et les Veilleurs, étant les representants du Prince, ne sont pas soumis à cet Edit.

Order is to be guarranteed by the Prince, who thus gather exclusively for himself the means to warrant the order and well

being of Kindred and Kine. Thus it is strictly forbidden to influence the police and army forces.

The Masques, being the representatives of the Prince, are not submitted to this Edict.

Diablerie / Diablerie

La Diablerie est un acte infâme indigne de notre Condition. Tout Caïnite convaincu de Diablerie sera passible d'une Chasse

de Sang, et ce, quel qu'ait été le Calice, ou l'endroit du crime.

Diablerie is an atrocious action under our condition. Any Kindred guilty of Diablerie can be Blood Hunted,

no matter who was the victim and where it happened.

L'Amaranthe / The Amaranth

Ceux qui se seront montré particulièrement indigne de leur Sang pourront voir leur Sang arraché par l'Amaranthe. Seuls

ceux qui auront été dignes des Traditions et Edits de Paris pourront se voir peut-être accordé par l'Ancien parmis les

Anciens, l'Amaranthe.

Those who acted in ways unworthy of their Blood can be subject to the Amaranth. Those who acted in ways worthy of their

Blood and of the Traditions and Edicts can be given the right of Amaranth by the Eldest among you.

La Magye / The Magick

Pratiquer les rituels magiques en présence d'un Mage est strictement interdit, tout comme tout contact avec eux.

Leur guerre d'ascension n'est pas la nôtre. Clan Tremere Le retour à Paris est conditionné par le comportement de leurs membres.

Les Veilleurs ne sont pas soumis à cet édit.

Praticing magic rituals in presence of a Mage is strictly forbidden, as is any contact with them. Their Ascensíon war is not our own. Clan Tremere Returning to

Paris is conditioned by the behaviour of their members.

The Veilleurs are not submitted to this Edict.

Assamites

Brujah

- -- Benedicte Dalouche -- Currently in Berlin...but wanting to return.

- -- L'Homme de Peu de Foi

- -- Saint Just 8th Generation, childe of Robin Leeland, sire of Karl.

- -- Thomas Frère(Thomas, Brother); 6th Generation Duc of the Brujah.

The Bâtards/ Catiff

Daughters of Cacophony

Followers of Set

- -- Theti-Sheri

- -- Samson Aersenns

Gangrel

- -- Niels Frank; - Progeny of Lord William Harper

- -- Jaques La Pul; - Childe of Niels Frank

- -- Jean-Luc Laupier - Progeny of Lord William Harper

Malkavian

- -- João Henrique

- -- Rochelle Dalmar

- -- Pierre Lavosh

Nosferatu

Toreador

- - Francois Villon -- Domain: The Louvre {Location: Right Bank of the Seine in the 1st arrondissement.}

- - Arnaud -- Domain: Club Elysée {Location: 8th Arrondissement}

- - Carla Gagnon -- Domain: Église de Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet {Location: 5th Arrondissement}

- - Maxime -- Domain: Saint-Georges -- A neighborhood of Pigalle -- Maxime has a loft above the vaunted SACEM building that he uses as his haven. {Location: 9th Arrondissement}

- - Bernard -- Domain: The Louvre {Location: Right Bank of the Seine in the 1st arrondissement.} -- As the Seneschal of Paris, Bernard resides with his sire in the Louvre.

- - Chevalier d'Eglantine -- Domain: Les Invalides {Location: 7th Arrondissement}

- Merevith

- - Elle Emilie Nicoline

- - Lazlo Guerin -- Domain: Palais Bourbon {Location: 7th Arrondissement}

- - Florient (Deceased)

- - Versancia

- - Violetta Desjardins

- - Arnaud -- Domain: Club Elysée {Location: 8th Arrondissement}

Tremere

- -- Lazare Monet -- Creator of La Transsubstantiation de la Cuisine.

- -- Czere Ubireg -- Turkish Apprentice

True Brujah

Ventrue

Websites

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_between_the_Wars_(1919%E2%80%931939)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belle_%C3%89poque

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_in_the_Belle_%C3%89poque