New Orleans

Despite the innumerable hardships placed in its path, New Orleans always seems to rise from the very ashes of destruction -- indeed, to transcend its former glory.

Despite the fires that have nearly reduced her Gothic splendor to memory, she still survives. Despite the power struggles that threaten to tear the city apart, she prospers under the almost feudal rule of her prince and his council. Despite laws that bar certain vampires from the city, still New Orleans draws refugees as a beacon in the darkness.

Despite all these obstacles and more, the city endures, as immortal as the Kindred who reside within. Perhaps, when even they have passed into memory, the city they called home will yet still survive.

Contents

- 1 Quote

- 2 Appearance

- 3 Location

- 4 Climate

- 5 Geography

- 6 History

- 7 Population

- 8 Economy

- 9 Arenas

- 10 Attractions

- 11 Bars and Clubs

- 12 Cemeteries

- 13 City Government

- 14 Crime

- 15 Citizens of New Orleans

- 16 Current Events

- 17 Festivals

- 18 Galleries

- 19 Haunted Houses

- 20 Holy Ground

- 21 Hospitals

- 22 Hotels & Hostels

- 23 Landmarks

- 24 Les Gens Des Ténèbres

- 25 Monasteries

- 26 Monuments

- 27 Museums

- 28 Parks

- 29 Periodicals

- 30 Private Residences

- 31 Restaurants

- 32 Schools

- 33 Shops

- 34 Theatres

- 35 Transportation

- 36 The Kithain of the City that Care Forgot

- 37 Crescent City Mages

- 38 Les Gens Des Ténèbres: The Kindred of Nawlins

- 39 La poubelle sans y être invité: The Uninvited Few

- 40 Werewolves of the Local Bayous

- 41 The Wraiths of the NOLA Necropolis

- 42 Websites

Quote

"It is the most congenial city in America that I know of and it"

"is due in large part, I believe, to the fact that here at last on this bleak"

"continent that sensual pleasures assume the importance which they deserve..."

- -- Henry Miller, The Air-Conditioned Nightmare

- -- Henry Miller, The Air-Conditioned Nightmare

Appearance

Location

New Orleans is located at 29°57′53″N 90°4′14″W (29.964722, −90.070556) on the banks of the Mississippi River, approximately 105 miles (169 km) upriver from the Gulf of Mexico. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 350.2 square miles (907 km2), of which 180.56 square miles (467.6 km2), or 51.55%, is land. The city is located in the Mississippi River Delta on the east and west banks of the Mississippi River and south of Lake Pontchartrain. The area along the river is characterized by ridges and hollows.

Climate

The climate of New Orleans is humid subtropical with short, generally mild winters and hot, humid summers. The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 53.4 °F (11.9 °C) in January to 83.3 °F (28.5 °C) in July and August. The lowest recorded temperature was 6 °F (−14 °C) on February 13, 1899. The highest recorded temperature was 104 °F (40 °C) on June 24, 2009. The average precipitation is 62.7 inches (1,590 mm) annually; the summer months are the wettest, while October is the driest month. Precipitation in winter usually accompanies the passing of a cold front. On average, there are 77 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs, 8.1 days per winter where the high does not exceed 50 °F (10 °C), and 8.0 nights with freezing lows annually; in a typical year the coldest night will be around 30 °F (−1 °C).[62] It is rare for the temperature to reach 100 °F (38 °C) or dip below 25 °F (−4 °C).

Hurricanes pose a severe threat to the area, and the city is particularly at risk because of its low elevation, and because it is surrounded by water from the north, east, and south, and Louisiana's sinking coast. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, New Orleans is the nation's most vulnerable city to hurricanes. Indeed, portions of Greater New Orleans have been flooded by: the Grand Isle Hurricane of 1909, the New Orleans Hurricane of 1915, 1947 Fort Lauderdale Hurricane, Hurricane Flossy in 1956, Hurricane Betsy in 1965, Hurricane Georges in 1998, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, and Hurricane Gustav in 2008, with the flooding in Betsy being significant and in a few neighborhoods severe, and that in Katrina being disastrous in the majority of the city.

New Orleans experiences snowfall only on rare occasions. A small amount of snow fell during the 2004 Christmas Eve Snowstorm and again on Christmas (December 25) when a combination of rain, sleet, and snow fell on the city, leaving some bridges icy. Before that, the last White Christmas was in 1964 and brought 4.5 inches (11 cm). Snow fell again on December 22, 1989, when most of the city received 1–2 inches (2.5–5.1 cm).

The last significant snow fall in New Orleans was on the morning of December 11, 2008.

Geography

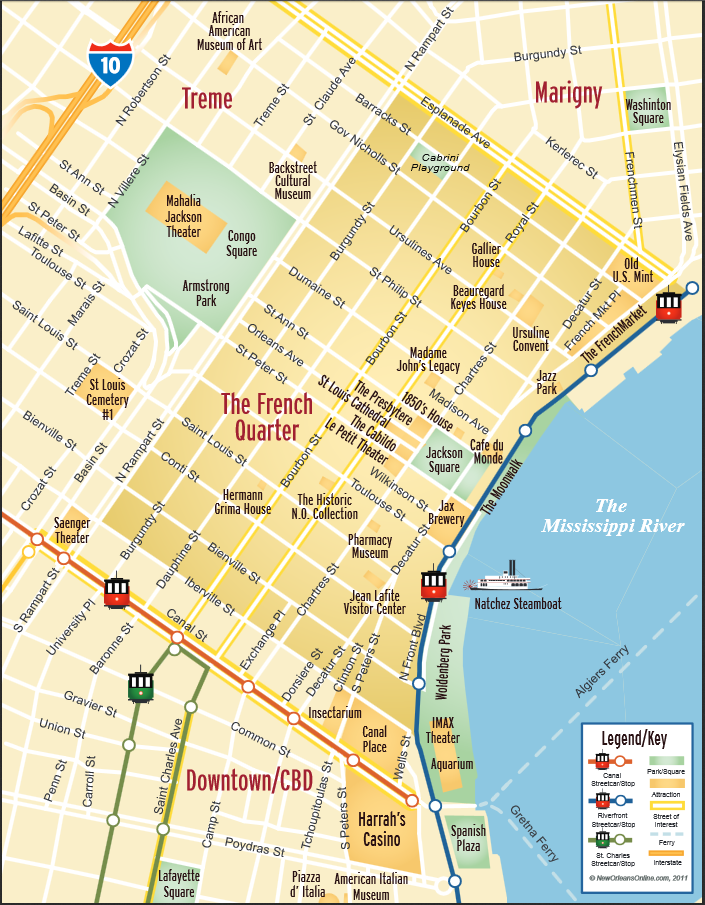

http://www.neworleansonline.com/tools/transportation/maps.html

French Quarter

History

New Orleans' history began long before Jean Baptiste le Moyne founded the city on the banks of the Mississippi River in 1718. It began in the second century B.C.E., when the majestic city of Carthage was destroyed by Roman legions under the control of Ventrue and Malkavian vampires. What became New Orleans started as the dream of a young tribune in the Roman army.

An Ancient Dream

The tribune, Gaius Marcellus, was 23 years old when he was fatally wounded during the assault on Carthage. He had already attracted the attention of a Ventrue leader, however, and this Ventrue did not let him die. Impressed by Gaius' ability, intelligence and abilities as an orator and writer, he Embraced the tribune, keeping the neonate by his side to record the events of the war.

Gaius soon realized that the war involved more than mortal goals. During lulls in the battles, the Ventrue elder told his newly created childe of the Jyhad fought by the Kindred. The young tribune saw the Ventrue role in the war being waged on Carthage; he did not, however, understand why Rome's Kindred waged such a senseless war on their brethren. Gaius felt that vampires who had build such a city as Carthage and established it with such noble ideals should be supported, not attacked.

For several decades the neonate stayed with his sire and served well in his post, but the senselessness of the Jyhad and his sire's role in it caused him to leave Rome. Heading north, Gaius settled finally in Gaul, which would later become France.

During the centuries Gaius lived in the French territory, he never forgot the city that he had helped to destroy. In his journals he chronicled what he could remember of Carthage: its ideals, policies, and the beliefs and dreams of those who had lived there. He kept these books with him, and when he Embraced his first childe, he showed him these books and taught him all he could recall of the noble city.

The childe was Doran, a young philosopher studying the desires and drives of mortal life. After the Embrace he turned his interests to Kindred social structures. Doran found special interest in his sire's stories of Carthage. Although the city defied his understanding of vampiric society, Doran believed the city could be reborn. Europe, however, was too corrupt to support so noble a city.

Doran had heard stories of a new world across the great ocean, where mortals had traveled to start a new civilization, free from the restrictions and laws of oppressive rulers. In the early 1600s, Doran made the dangerous journey across the Atlantic Ocean to the New World. Gaius stayed in France, though he told his childe he shared and supported the dream of resurrecting Carthage.

Arriving on the northeastern coast, Doran soon found things were not as he had been told. The laws and oppression of the old continent stretched across the waters, and the old tyrants still held the new land within their grasp. During the early 1700s, Doran migrated with the other Kindred who followed the flow of the mortal herd over the mountains, ever seeking their elusive freedoms.

Most went north to Canada, but Doran journeyed south. He settled in the northern Louisiana territory, having heard tales of strange and dangerous creatures that inhabited the swamps to the south.

The Colonial Era

Before the founding of what would become known as the city of New Orleans, the area was inhabited by Native Americans for thousands of years. The Mississippian culture peoples built mounds and earthworks in the area. Later Native Americans created a portage between the headwaters of Bayou St. John (known to the natives as Bayouk Choupique) and the Mississippi River. The bayou flowed into Lake Pontchartrain. This became an important trade route. Archaeological evidence has shown settlement here dated back to at least 400 C.E.

French explorers, fur trappers and traders arrived in the area by the 1690s, some making settlements amid the Native American village of thatched huts along the bayou. By the end of the decade, the French made an encampment called "Port Bayou St. Jean" near the head of the bayou. They built a small fort "St. Jean" at the mouth of the bayou in 1701, used as a large Native American shell midden dating back to the Marksville culture. These early European settlements were then within the limits of the city of New Orleans, though predating its official date of founding.

The War Begins

The arrival of a second vampire in the territory caught Doran unaware, but the newcomer did not keep his presence a secret for long. Simon de Cosa, a Spanish Brujah, attacked Doran one night in 1713. Doran fought back with all the powers at his disposal and managed to escape his savage assailant. Returning to his haven, he ordered his servants into action, and for the next several years skirmishes between the vampires' mortal followers became all too common.

Early in their fighting, Doran made Jean Baptiste le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, the young governor of the territory, his ghoul. Outraged that Doran had gained control of Bienville, Cosa began establishing his own power, gaining control over many of the town's other influential men. Manipulating his new pawns, Cosa began to extert pressure on Bienville's office. Kindred allies across the sea assisted both vampires in their feud.

Cosa finally managed to instigate enough of an outcry to have Doran's ghoul removed from office. Acting quickly, Cosa soon had his own servant, Antoine Cadillac, appointed as governor of the Louisiana Territory.

In order to rid himself completely of Bienville's threat, Cosa called into play his pawns among the American Indians, ordering them on raids of small settlements. As soon as the attacks started, Cosa had Cadillac outfit Bienville with a small army and sent the former governor to handle the Indian uprisings. It was Cosa's firm hope that Doran's ghoul would die in one of the battles, but in 1716 Bienville defeated the fiercest of Cosa's Indian tribes, the Natchez. The unexpected victory destroyed many of Cosa's plans and led to Bienville's reinstatement as governor of Louisiana.

New Orleans

New Orleans was founded in 1718 by the French as Nouvelle-Orléans, under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville. The site was selected because it was relatively high ground along the flood-prone banks of the lower Mississippi, and was adjacent to the trading route and portage between the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain via Bayou St. John. From its founding, the French intended it to be an important colonial city. The city was named in honor of the then Regent of France, Philip II, Duke of Orléans.

In 1718, after two years had passed with no sign of Cosa, Bienville formally established the city of New Orleans. Although Cosa did attempt to regain his territory in 1720, he had little support and was defeated. Forced to retreat, Cosa and his followers escaped into the swamplands.

The priest-chronicler Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix described it in 1721 as a place of a hundred wretched hovels in a malarious wet thicket of willows and dwarf palmettos, infested by serpents and alligators; he seems to have been the first, however, to predict for it an imperial future. In 1722, Nouvelle-Orléans was made the capital of French Louisiana, replacing Biloxi in that role. In September of that year, a hurricane struck the city, blowing most of the structures down. After this, the administrators enforced the grid pattern dictated by Bienville but hitherto previously mostly ignored by the colonists. This grid is still seen today in the streets of the city's "French Quarter".

For the next forty years, Cosa continued his war against Doran. While trying to protect the city and simultaneously establishing what would become an extremely effective intelligence network, Doran also tried to reason with his adversary, hoping to make Cosa share his dream for New Orleans. Doran hoped that by relating stories of the great city of Carthage, as well as his own plans for New Orleans, he could win the Brujah's support rather than his opposition.

Cosa, however, showed no interest int he Ventrue's visions and continued to try to unseat his rival. Though he came close several times, Cosa never managed to take the territory. Many of Cosa's attacks were made through Native American followers. Under Cosa's direction, native tribes raided the city and other settlements. In 1736, the Chickasaws defeated Bienville. The tribe continued to menace the area for the next quarter century, but never managed to gain much power for Cosa.

The closest Cosa came to success was in 1743, when Doran lost his hold over Bienville. The ghoul freed himself with the help of a mage and returned to Europe. Cosa, feeling that Doran would be severely handicapped without his ghoul, struck with his small band of followers. What Cosa had not anticipated, however, was exactly how many mortals Doran now had under his control. Defeated in his attempt, Cosa and his followers retreated from the area.

Much of the population in the early days was of the wildest and, in part, of the most undesirable character: deported galley slaves, trappers, gold-hunters and city scourings; and the governors' letters are full of complaints regarding the riffraff sent as soldiers as late as Kerlerec's administration from 1753 to 1763. Two lakes in the vicinity, Lake Pontchartrain and Maurepas, commemorate respectively Louis Phelypeaux, Count Pontchartrain, minister and chancellor of France, and Jean Frederic Phelypeaux, Count Maurepas, minister and secretary of state; a third is really a landlocked inlet of the sea, and its name (Lake Borgne) has reference to its incomplete or defective character.

The Lupines

Another attempt that nearly succeeded for Cosa came in 1755 when England took possession of Arcadia, which is today Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. All in the territory were required to take an oath of allegiance to England. Six thousand people refused and were deported from the territory. A small band of these displaced refugees settled in New Orleans and the surrounding area. These people became known as Cajuns.

A small tribe of Lupines followed their Cajun kinfolk to the Louisiana bayous. There they discovered the Uktena tribe, as well as a caern. Battles soon broke out between the newcomers and the Uktena. Cosa chose this time to attack Doran, believing that the Lupines would cause trouble for the Ventrue in their attempts to reestablish their territory. Again, however, Cosa underestimated Doran's forces. During the short-lived battle, Cosa learned the lengths to which Doran was willing to go to see his dream realized.

Doran could not help but see the war between the Lupine tribes as an unsolicited opportunity to further his ambitions for New Orleans. After the old Uktena chief died, Doran, with the help of a recently arrived Gangrel, arranged a meeting with the new leader, Lucius Jackson. Doran offered to help Jackson's tribe drive the newcomers from the area and to help the Uktena should they try to return. In exchange for this help, Doran asked Jackson to assist him in the fight against Cosa and to respect the city's boundaries. Jackson agreed to Doran's proposal, though he privately expressed contempt for the offer. He told other tribe members the vampires would be their next foes after the newcomers were defeated.

Much to Jackson's surprise, the tide of the battle quickly shifted when the vampires entered the fighting. The newcomers, who Jackson said were called Black Spiral Dancers, were soon driven from the territory and into the swamplands west of the city.

Cosa was not ready to deal with the Uktena as well as Doran, and the vampire-werewolf alliance forced him to the western swamps as well. With both of their enemies defeated, Doran and Jackson devised a mutually satisfactory treaty. Its tenets were simple enough, though the passing of but a few decades proved them overly vague. Essentially, the land treaty gave control of the bayous and swamplands to the Lupines, while the territory and affairs of the city and the mortal population within it were left to the Kindred. While not all were satisfied, most Kindred and Lupines agreed to abide by the treaty.

Spanish Rule

In 1763 following Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War, the French colony west of the Mississippi River—plus New Orleans—was ceded to the Spanish Empire as a secret provision of the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau, confirmed the following year in the Treaty of Paris. This was to compensate Spain for the loss of Florida to the British, who also took the remainder of the formerly French territory east of the River.

No Spanish governor came to take control until 1766. French and German settlers, hoping to restore New Orleans to French control, forced the Spanish governor to flee to Spain in the bloodless Rebellion of 1768. A year later, the Spanish reasserted control, executing five ringleaders and sending five plotters to a prison in Cuba, and formally instituting Spanish law. Other members of the rebellion were forgiven as long as they pledged loyalty to Spain. Although a Spanish governor was in New Orleans, it was under the jurisdiction of the Spanish garrison in Cuba.

In the final third of the Spanish period, two massive fires burned the great majority of the city's buildings. The Great New Orleans Fire of 1788 destroyed 856 buildings in the city on Good Friday, March 21 of that year. In December 1794 another fire destroyed 212 buildings. After the fires, the city was rebuilt with bricks, replacing the simpler wooden buildings constructed in the early colonial period. Much of the 18th-century architecture still present in the French Quarter was built during this time, including three of the most impressive structures in New Orleans—St. Louis Cathedral, the Cabildo and the Presbytere. While the architecture from this period is commonly attributed to French influence, characteristics of the French Quarter, such as multi-storied buildings centered around inner courtyards, large arched doorways, and the use of decorative wrought-iron, were most ubiquitous in parts of Spain and the Spanish colonies. This influence may be attributed to the fact that the period of Spanish rule saw a great deal of immigration from all over the Atlantic, including Spain and the Canary Islands, and the Spanish colonies. In addition, it should be noted that while the architectural style of New Orleans, with its wrought iron balconies and full-height windows may remind one of Paris, many of New Orleans's oldest buildings actually predate the Haussman Projects that later renovated large areas of Paris in this same style.

In 1795 and 1796, the sugar processing industry was first put upon a firm basis. The last twenty years of the 18th century were especially characterized by the growth of commerce on the Mississippi, and the development of those international interests, commercial and political, of which New Orleans was the center. Within the city, the Carondelet Canal, connecting the back of the city along the river levee with Lake Pontchartrain via Bayou St. John, opened in 1794, which was a boost to commerce.

Through Pinckney's Treaty signed on October 27, 1795, Spain granted the United States "Right of Deposit" in New Orleans, allowing Americans to use the city's port facilities.

The 19th Century

Retrocession to France and Louisiana Purchase

In 1800 Spain and France signed the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso stipulating that Spain give Louisiana back to France, although it had to remain under Spanish control as long as France wished to postpone the transfer of power. There was another relevant treaty in 1801, the Treaty of Aranjuez, and later a royal bill issued by King Charles IV of Spain in 1802; these confirmed and finalized the retrocession of Spanish Louisiana to France.

In April 1803, Napoleon sold Louisiana (New France) (which then included portions of more than a dozen present-day states) to the U.S. in the Louisiana Purchase. A French prefect, Pierre Clément de Laussat, who had only arrived in New Orleans on March 23, 1803, formally took control of Louisiana for France on November 30, only to hand it over to the U.S. on December 20, 1803. In the meantime he created New Orleans' first city council, abolishing the Spanish cabildo.

In 1805, a census showed a heterogeneous population of 8,500, comprising 3,551 whites, 1,556 free blacks, and 3,105 slaves. Observers at the time and historians since believe there was an undercount and the true population was about 10,000.

Early 19th Century Commercial Growth

The next dozen years were marked by the beginnings of self-government in city and state; by the excitement attending the Aaron Burr conspiracy (in the course of which, in 1806–1807, General James Wilkinson practically put New Orleans under martial law); by the immigration from Cuba of French planters; and by the American War of 1812. From early days it was noted for its cosmopolitan polyglot population and mixture of cultures. The city grew rapidly, with influxes of Americans, African, French and Creole French (people of French descent born in the Americas) and Creoles of Color (people of mixed European and African ancestry), many of the latter two groups fleeing from the revolution in Haiti.

The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) established the second republic in the Western Hemisphere and the first led by blacks. Haitian refugees, both white and free people of color (affranchis or gens de couleur libres), arrived in New Orleans, often bringing slaves with them. While Governor Claiborne and other officials wanted to keep out more free black men, French Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking population. As more refugees were allowed in Louisiana, Haitian émigrés who had gone to Cuba also arrived. Nearly 90 percent of the new immigrants settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites; 3,102 free persons of African descent; and 3,226 additional enslaved individuals to the city, doubling its French-speaking population. In addition, an 1809-1810 migration brought thousands of white francophone refugees from Saint-Domingue (deported by officials in Cuba in response to Bonapartist schemes in Spain).

1811 German Coast Uprising (Slave Revolt)

The Haitian Revolution also increased ideas of resistance among the slaves of New Orleans. Early in 1811, hundreds of slaves revolted in what became known as the 1811 German Coast Uprising. The uprising occurred on the east bank of the Mississippi River in St. John the Baptist and St. Charles Parishes, Louisiana. While the slave insurgency was the largest in U.S. history, the rebels killed only two white men. Confrontations with militia and executions after so-called trials killed ninety-five black people.

Between 64 and 125 enslaved men marched from sugar plantations near present-day LaPlace on the German Coast toward the city of New Orleans. They collected more men along the way. Some accounts claimed a total of 200-500 slaves participated. During their two-day, twenty-mile march, the men burned five plantation houses (three completely), several sugar houses (small sugar mills), and crops. They were armed mostly with hand tools.

White men led by officials of the territory formed militia companies to hunt down and kill the insurgents, backed up by the United States Army under the command of Brigadier General Wade Hampton I, a slaveholder himself. Over the next two weeks, white planters and officials interrogated, sentenced, and carried out summary executions of an additional 44 insurgents who had been captured. The tribunals were held in three locations, in the two parishes involved and in Orleans Parish (New Orleans). Executions were by hanging, decapitation, or firing squad (St. Charles Parish). Whites displayed the bodies as a warning to intimidate slaves. The heads of some were put on pikes and displayed along the River Road and at the Place d'Armes in New Orleans.

Since 1995 the African American History Alliance of Louisiana has led an annual commemoration in January of the uprising, in which they have been joined by some descendants of participants in the revolt.

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, the British sent a large force to conquer the city, but they were defeated early in 1815 by Andrew Jackson's combined forces some miles downriver from the city at Chalmette's plantation, during the Battle of New Orleans. The American government managed to obtain early information of the enterprise and prepared to meet it with forces (regular, militia, and naval) under the command of Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson. Privateers led by Jean Lafitte were also recruited for the battle.

The British advance was made by way of Lake Borgne, and the troops landed at a fisherman's village on December 23, 1814, Major-General Sir Edward Pakenham taking command there two days later (Christmas). An immediate advance on the still insufficiently-prepared defenses of the Americans might have led to the capture of the city; but this was not attempted, and both sides limited themselves to relatively small skirmishes and a naval battle while awaiting reinforcements. At last in the early morning of January 8, 1815 (after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed but before the news had reached across the Atlantic), a direct attack was made on the now strongly-entrenched line of defenders at Chalmette, near the Mississippi River. It failed disastrously with a loss of 2,000 out of 9,000 British troops engaged, among the dead being Pakenham and Major-General Gibbs. The expedition was soon afterwards abandoned and the troops embarked, under the command of John Lambert. Another engagement followed: a ten-day artillery battle at Fort St. Philip on the lower Mississippi River. The British fleet set sail on January 18 and went on to capture Fort Bowyer at the entrance to Mobile Bay.

General Jackson had arrived in New Orleans in early December 1814, having marched overland from Mobile in the Mississippi Territory. His final departure was not until mid-March 1815. Martial law was maintained in the city throughout the period of three and a half months.

Antebellum New Orleans

The population of the city doubled in the 1830s with an influx of settlers. A few newcomers to the city were friends of the Marquis de Lafayette who had settled in the newly founded city of Tallahassee, Florida, but due to legalities had lost their deeds. One new settler who was not displaced but chose to move to New Orleans to practice law was Prince Achille Murat, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. According to historian Paul Lachance, “the addition of white immigrants to the white creole population enabled French-speakers to remain a majority of the white population until almost 1830. If a substantial proportion of free persons of color and slaves had not also spoken French, however, the Gallic community would have become a minority of the total population as early as 1820.” Large numbers of German and Irish immigrants began arriving at this time. The population of the city doubled in the 1830s and by 1840 New Orleans had become the wealthiest and third-most populous city in the nation.

By 1840, the city's population was approximately 102,000 and it was now the third-largest in the U.S, the largest city away from the Atlantic seaboard as well as the largest in the South.

The introduction of natural gas (about 1830); the building of the Pontchartrain Rail-Road (1830–31), one of the earliest in the United States; the introduction of the first steam-powered cotton press (1832), and the beginning of the public school system (1840) marked these years; foreign exports more than doubled in the period 1831–1833. In 1838 the commercially-important New Basin Canal opened a shipping route from the Lake to uptown New Orleans. Travelers in this decade have left pictures of the animation of the river trade more congested in those days of river boats, steamers, and ocean-sailing craft than today; of the institution of slavery, the quadroon balls, the medley of Latin tongues, the disorder and carousing of the river-men and adventurers that filled the city. Altogether there was much of the wildness of a frontier town, and a seemingly boundless promise of prosperity. The crisis of 1837, indeed, was severely felt, but did not greatly retard the city's advancement, which continued unchecked until the Civil War. In 1849 Baton Rouge replaced New Orleans as the capital of the state. In 1850 telegraphic communication was established with St. Louis and New York City; in 1851 the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern railway, the first railway outlet northward, later part of the Illinois Central, and in 1854 the western outlet, now the Southern Pacific, were begun.

In 1836 the city was divided into three municipalities: the first being the French Quarter and Faubourg Tremé, the second being Uptown (then meaning all settled areas upriver from Canal Street), and the third being Downtown (the rest of the city from Esplanade Avenue on, downriver). For two decades the three Municipalities were essentially governed as separate cities, with the office of Mayor of New Orleans having only a minor role in facilitating discussions between municipal governments.

The importance of New Orleans as a commercial center was reinforced when the United States Federal Government established a branch of the United States Mint there in 1838, along with two other Southern branch mints at Charlotte, North Carolina, and Dahlonega, Georgia. Although there was an existing coin shortage, the situation became much worse because in 1836 President Andrew Jackson had issued an executive order, called a specie circular, which demanded that all land transactions in the United States be conducted in cash, thus increasing the need for minted money. In contrast to the other two Southern branch mints, which only minted gold coins, the New Orleans Mint produced both gold and silver coinage, which perhaps marked it as the most important branch mint in the country.

The mint produced coins from 1838 until 1861, when Confederate forces occupied the building and used it briefly as their own coinage facility until it was recaptured by Union forces the following year.

On May 3, 1849, a Mississippi River levee breach upriver from the city (around modern River Ridge, Louisiana) created the worst flooding the city had ever seen. The flood, known as at Sauvé's Crevasse, left 12,000 people homeless. While New Orleans has experienced numerous floods large and small in its history, the flood of 1849 was of a more disastrous scale than any save the flooding after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. New Orleans has not experienced flooding from the Mississippi River since Sauvé's Crevasse, although it came dangerously close during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.

The First American Civil War

Early in the American Civil War New Orleans was captured by the Union without a battle in the city itself, and hence was spared the destruction suffered by many other cities of the American South. It retains a historical flavor with a wealth of 19th century structures far beyond the early colonial city boundaries of the French Quarter.

The political and commercial importance of New Orleans, as well as its strategic position, marked it out as the objective of a Union expedition soon after the opening of the Civil War. Elements of the Union Blockade fleet arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi on 27 May 1861. An effort to drive them off lead to the Battle of the Head of Passes on 12 October 1861. Captain D.G. Farragut and the Western Gulf squadron sailed for New Orleans in January 1862. The main defenses of the Mississippi consisted of the two permanent forts, Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip. On April 16, after elaborate reconnaissances, the Union fleet steamed up into position below the forts and opened fire two days later. Within days, the fleet had bypassed the forts in what was known as the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip. At noon on the 25th, Farragut anchored in front of New Orleans. Forts Jackson and St. Philip, isolated and continuously bombarded by Farragut's mortar boats, surrendered on the 28th, and soon afterwards the military portion of the expedition occupied the city resulting in the Capture of New Orleans.

The commander, General Benjamin Butler, subjected New Orleans to a rigorous martial law so tactlessly administered as greatly to intensify the hostility of South and North. Butler's administration did have benefits to the city, which was kept both orderly and due to his massive cleanup efforts unusually healthy by 19th century standards. Towards the end of the war General Nathaniel Banks held the command at New Orleans.

The Era of Reconstruction

The city again served as capital of Louisiana from 1865 to 1880. Throughout the years of the Civil War and the Reconstruction period the history of the city is inseparable from that of the state. All the constitutional conventions were held here, the seat of government again was here (in 1864–1882) and New Orleans was the center of dispute and organization in the struggle between political and ethnic blocks for the control of government.

There was a major street riot of July 30, 1866, at the time of the meeting of the radical constitutional convention. Businessman Charles T. Howard began the Louisiana State Lottery Company in an arrangement which involved bribing state legislators and governors for permission to operate the highly lucrative outfit, as well as legal manipulations that at one point interfered with the passing of one version of the state constitution.

During Reconstruction, New Orleans was within the Fifth Military District of the United States. Louisiana was readmitted to the Union in 1868, and its Constitution of 1868 granted universal manhood suffrage. Both blacks and whites were elected to local and state offices. In 1872, then-lieutenant governor P.B.S. Pinchback succeeded Henry Clay Warmouth as governor of Louisiana, becoming the first non-white governor of a U.S. state, and the last African American to lead a U.S. state until Douglas Wilder's election in Virginia, 117 years later. In New Orleans, Reconstruction was marked by the Mechanics Institute race riot (1866). The city operated successfully a racially integrated public school system. Damage to levees and cities along the Mississippi River adversely affected southern crops and trade for the port city for some time, as the government tried to restore infrastructure. The nationwide Panic of 1873 also slowed economic recovery.

In the 1850s white Francophones had remained an intact and vibrant community, maintaining instruction in French in two of the city's four school districts. As the Creole elite feared, during the war, their world changed. In 1862, the Union general Ben Butler abolished French instruction in schools, and statewide measures in 1864 and 1868 further cemented the policy. By the end of the 19th century, French usage in the city had faded significantly.

New Orleans annexed the city of Algiers, Louisiana, across the Mississippi River, in 1870. The city also continued to expand upriver, annexing the town of Carrollton, Louisiana in 1874.

On September 14, 1874 armed forces led by the White League defeated the integrated Republican metropolitan police and their allies in pitched battle in the French Quarter and along Canal Street. The White League forced the temporary flight of the William P. Kellogg government, installing John McEnery as Governor of Louisiana. Kellogg and the Republican administration were reinstated in power 3 days later by United States troops. Early 20th century segregationists would celebrate the short-lived triumph of the White League as a victory for "white supremacy" and dubbed the conflict "The Battle of Liberty Place". A monument commemorating the event still stands near the foot of Canal Street, to the side of the Aquarium near the trolley tracks.

U.S. troops also blocked the White League Democrats in January 1875, after they had wrested from the Republicans the organization of the state legislature. Nevertheless, the revolution of 1874 is generally regarded as the independence day of Reconstruction, although not until President Hayes withdrew the troops in 1877 and the Packard government fell did the Democrats actually hold control of the state and city. The financial condition of the city when the whites gained control was very bad. The tax-rate had risen in 1873 to 3%. The city defaulted in 1874. On the interest of its bonded debt, it later refunded this ($22,000,000 in 1875) at a lower rate, to decrease the annual charge from $1,416,000 to $307,500.

The New Orleans Mint was reopened in 1879, minting mainly silver coinage, including the famed Morgan silver dollar from 1879 to 1904.

The city suffered flooding in 1882.

The city hosted the 1884 World's Fair, called the World Cotton Centennial. A financial failure, the event is notable as the beginnings of the city's tourist economy.

An electric lighting system was introduced to the city in 1886; limited use of electric lights in a few areas of town had preceded this by a few years.

1890s

On October 15, 1890, Chief-of-Police David C. Hennessy was shot, and reportedly his dying words informed a colleague that he was shot by "Dagos", an insulting term for Italians. On March 13, 1891, a group of Italian Americans on trial for the shooting were acquitted. However, a mob stormed the jail and lynched eleven Italian-Americans. Local historians still debate whether some of those lynched were connected to the Mafia, but most agree that a number of innocent people were lynched during the Chief Hennessy Riot. The government of Italy protested, as some of those lynched were still Italian citizens, and the government of the U.S. eventually paid reparations to Italy.

In the 1890s much of the city's public transportation system, hitherto relying on mule-drawn streetcars on most routes supplemented by a few steam locomotives on longer routes, was electrified.

With a large educated colored population that had long interacted with the white population, racial attitudes were comparatively liberal for the Deep South. Many in the city objected to the government of the State of Louisiana's attempt to enforce strict racial segregation, and hoped to overturn the law with a test case in 1892. The case found its way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896 as Plessy v. Ferguson. This resulted in upholding segregation, which would be enforced with ever-growing strictness for more than half a century.

In 1892, the New Orleans political machine, "the Ring," won a sweeping victory over the incumbent reformers. John Fitzpatrick, leader of the working class Irish, became mayor. In 1896 Mayor Fitzpatrick proposed combining existing library resources to create the city's first free public library, the Fisk Free and Public Library. This entity later became known as the New Orleans Public Library.

In the spring of 1896 Mayor Fitzpatrick, leader of the city's Bourbon Democratic organization, left office after a scandal-ridden administration, his chosen successor badly defeated by reform candidate Walter C. Flower. But Fitzpatrick and his associates quickly regrouped, organizing themselves on 29 December into the Choctaw Club, which soon received considerable patronage from Louisiana governor and Fitzpatrick ally Murphy Foster. Fitzpatrick, a power at the 1898 Louisiana Constitutional Convention, was instrumental in exempting immigrants from the new educational and property requirements designed to disenfranchise blacks. In 1899 he managed the successful mayoral campaign of Bourbon candidate Paul Capdevielle.

In 1897 the quasi-legal red light district called Storyville opened and soon became a famous attraction of the city.

The Robert Charles Riots occurred in July 1900. Well-armed African-American Robert Charles held off a group of policemen who came to arrest him for days, killing several of them. A White mob started a race riot, terrorizing and killing a number of African Americans unconnected with Charles. The riots were stopped when a group of White businessmen quickly printed and nailed up flyers saying that if the rioting continued they would start passing out firearms to the Colored population for their self-defense.

Epidemics of the Late 19th Century

The population of New Orleans and other settlements in south Louisiana suffered from epidemics of yellow fever, malaria, cholera, and smallpox, beginning in the late 18th century and periodically throughout the 19th century. Doctors did not understand how the diseases were transmitted; primitive sanitation and lack of a public water system contributed to public health problems, as did the highly transient population of sailors and immigrants. The city successfully suppressed a final outbreak of yellow fever in 1905. (See below, 20th century.)

Progressive era drainage

Much of the city is located below sea level between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, so the city is surrounded by levees.

Until the early 20th century, construction was largely limited to the slightly higher ground along old natural river levees and bayous; the largest section of this being near the Mississippi River front. This gave the 19th-century city the shape of a crescent along a bend of the Mississippi, the origin of the nickname The Crescent City. Between the developed higher ground near the Mississippi and the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, most of the area was wetlands only slightly above the level of Lake Pontchartrain and sea level. This area was commonly referred to as the "back swamp," or areas of cypress groves as "the back woods." While there had been some use of this land for cow pasture and agriculture, the land was subject to frequent flooding, making what would otherwise be valuable land on the edge of a growing city unsuitable for development. The levees protecting the city from high water events on the Mississippi and Lake compounded this problem, as they also kept rainwater in, which tended to concentrate in the lower areas. 19th century steam pumps were set up on canals to push the water out, but these early efforts proved inadequate to the task.

Following studies begun by the Drainage Advisory Board and the Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans in the 1890s, in the 1900s and 1910s engineer and inventor A. Baldwin Wood enacted his ambitious plan to drain the city, including large pumps of his own design that are still used when heavy rains hit the city. Wood's pumps and drainage allowed the city to expand greatly in area.

It only became clear decades later that the problem of subsidence had been underestimated. Much of the land in what had been the old back swamp has continued to slowly sink, and many of the neighborhoods developed after 1900 are now below sea level.

20th Century

In the early part of the 20th century the Francophone character of the city was still much in evidence, with one 1902 report describing "one-fourth of the population of the city speaks French in ordinary daily intercourse, while another two-fourths is able to understand the language perfectly." As late as 1945, one still encountered elderly Creole women who spoke no English. The last major French language newspaper in New Orleans, L’Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans, ceased publication on December 27, 1923, after ninety-six years; according to some sources Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Orleans continued until 1955.

In 1905, yellow fever was reported in the city, which had suffered under repeated epidemics of the disease in the previous century. As the role of mosquitoes in spreading the disease was newly understood, the city embarked on a massive campaign to drain, screen, or oil all cisterns and standing water (breeding ground for mosquitoes) in the city and educate the public on their vital role in preventing mosquitoes. The effort was a success and the disease was stopped before reaching epidemic proportions. President Theodore Roosevelt visited the city to demonstrate the safety of New Orleans. The city has had no cases of Yellow Fever since.

In 1909, the New Orleans Mint ceased coinage, with active coining equipment shipped to Philadelphia.

New Orleans was hit by major storms in the 1909 Atlantic hurricane season and again in the 1915 Atlantic hurricane season.

In 1917 the Department of the Navy ordered the Storyville District closed, over the opposition of Mayor Martin Behrman.

In 1923 the Industrial Canal opened, providing a direct shipping link between Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River.

In the 1920s an effort to "modernize" the look of the city removed the old cast-iron balconies from Canal Street, the city's commercial hub. In the 1960s another "modernization" effort replaced the Canal Streetcar Line with buses. Both of these moves came to be regarded as mistakes long after the fact, and the streetcars returned to a portion of Canal Street at the end of the 1990s, and construction to restore the entire line was completed in April 2004.

The city's river levees narrowly escaped being topped in the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.

In 1927 a project was begun to fill in the shoreline of Lake Pontchartrain and create levees along the lake side of the city. Previously areas along the lakefront like Milneburg were built up on stilts, often over water of the constantly shifting shallow shores of the Lake.

There have often been tensions between the city, with its desire to run its own affairs, and the government of the State of Louisiana wishing to control the city. Perhaps the situation was never worse than in the early 1930s between Louisiana Gov. Huey P. Long and New Orleans Mayor T. Semmes Walmsley, when armed city police and state troopers faced off at the Orleans Parish line and armed conflict was only narrowly avoided.

During World War II, New Orleans was the site of the development and construction of Higgins boats under the direction of Andrew Higgins. General Dwight D. Eisenhower proclaimed these landing craft vital to the Allied victory in the war.

The suburbs saw great growth in the second half of the 20th century, and it was only in the post-World War II period that a truly metropolitan New Orleans comprising the New Orleans center city and surrounding suburbs developed. The largest suburb today is Metairie, an unincorporated subdivision of Jefferson Parish that borders New Orleans to the west. In a somewhat different postwar developmental pattern than that experienced by other older American cities, New Orleans' center city population grew for the first two decades after the war. This was due to the city's ability to accommodate large amounts of new, suburban-style development within the existing city limits, in such neighborhoods as Lakeview, Gentilly, Algiers and New Orleans East. Unlike some other municipalities, notably many in Texas, New Orleans is unable to annex adjacent suburban development.

Mayor DeLesseps "Chep" Morrison was elected as a reform candidate in 1946. He served as mayor of New Orleans until 1961, shaping the city's post-World War II trajectory. His energetic administration accomplished much and received considerable national acclaim. By the end of his mayoralty, however, his political fortunes were dwindling, and he failed to effectively respond to the growing Civil Rights movement.

The 1947 Fort Lauderdale Hurricane hit the city in September 1947. The levees & pumping system succeeded in protecting the city proper from major flooding, but many areas of the new suburbs in Jefferson Parish were deluged, and Moisant Airport was shut down under 2 feet (0.61 m) of water.

In January 1961 a meeting of the city's white business leaders publicly endorsed desegregation of the city's public schools. That same year Victor H. Schiro became the city's first mayor of Italian-American ancestry.

In 1965 the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet Canal ("MR GO", pronounced mister go) was completed, connecting the Intracoastal Waterway with the Gulf of Mexico. The Canal was expected to be an economic boom that would eventually lead to the replacement of the Mississippi Riverfront as the metro area's main commercial harbor. "MR GO" failed to live up to commercial expectations, and from its early days it was blamed for freshwater marsh-killing saltwater intrusion and coastal erosion, increasing the area's risk of hurricane storm surge.

In September 1965 the city was hit by Hurricane Betsy. Windows blew out of television station WWL while it was broadcasting. In an effort to prevent panic, mayor Vic Schiro memorably told TV and radio audiences "Don't believe any false rumors, unless you hear them from me." A breach in the Industrial Canal produced catastrophic flooding of the city's Lower 9th Ward as well as the neighboring towns of Arabi and Chalmette in St. Bernard parish. President Lyndon Johnson quickly flew to the city to promise federal aid.

In 1978, City Councilman Ernest N. Morial became the first person of African-American ancestry to be elected mayor of New Orleans.

While long one of the United States' most visited cities, tourism boomed in the last quarter of the 20th century, becoming a major force in the local economy. Areas of the French Quarter and Central Business District, which were long oriented towards local residential and business uses, increasingly catered to the tourist industry.

A century after the Cotton Centennial Exhibition, New Orleans hosted another World's Fair, the 1984 Louisiana World Exposition.

In 1986, Sidney Barthelemy was elected mayor of the Crescent City; he was re-elected in spring of 1990, serving two terms.

In 1994 and 1998, Marc Morial, the son of "Dutch" Morial, was elected to two consecutive terms as mayor.

The city experienced severe flooding in the May 8, 1995, Louisiana Flood when heavy rains suddenly dumped over a foot of water on parts of town faster than the pumps could remove the water. Water filled up the streets, especially in lower-lying parts of the city. Insurance companies declared more automobiles totaled than in any other U.S. incident up to that time. (See May 8th 1995 Louisiana Flood.)

On the afternoon of Saturday, December 14, 1996, the M/V Bright Field freightliner/bulk cargo vessel slammed into the Riverwalk mall and hotel complex on the Poydras Street Wharf along the Mississippi River. Amazingly, nobody died in the accident, although about 66 were injured. Fifteen shops and 456 hotel rooms were demolished. The freightliner was unable to be removed from the crash site until January 6, 1997, by which time the site had become something of a "must-see" tourist attraction.

21st Century

In May 2002, businessman Ray Nagin was elected mayor. A former cable television executive, Nagin was unaligned with any of the city's traditional political blocks, and many voters were attracted to his pledges to fight corruption and run the city on a more business-like basis. In 2014 Nagin was convicted on charges that he had taken more than $500,000 in payouts from businessmen in exchange for millions of dollars' worth of city contracts. He received a 10-year sentence.

On April 14, 2003, the 2003 John McDonogh High School shooting occurred at John McDonogh High School.

Hurricane Katrina

On August 29, 2005, an estimated 600,000 people were temporarily evacuated from Greater New Orleans when projected tracks of Hurricane Katrina included a possible major hit of the city. It missed, although Katrina wreaked considerable havoc on the Gulf Coast east of Louisiana.

The city suffered from the effects of a major hurricane on and after August 29, 2005, as Hurricane Katrina made landfall in the gulf coast near the city. In the aftermath of the storm, what has been called "the largest civil engineering disaster in the history of the United States" flooded the majority of the city when the levee and floodwall system protecting New Orleans failed.

On August 26, tracks which had previously indicated the hurricane was heading towards the Florida Panhandle shifted 150 miles (240 km) westward, initially centering on Gulfport/Biloxi, Mississippi and later shifted further westward to the Mississippi/Louisiana state line. The city became aware that a major hurricane hit was possible and issued voluntary evacuations on Saturday, August 27. Interstate 10 in New Orleans East and Jefferson and St. Charles parishes was converted to all-outbound lanes heading out of the city as well as Interstates 55 and 59 in the surrounding area, a maneuver known as "contraflow."

In the Gulf of Mexico, Katrina continued to gain strength as it turned northwest, then north towards southeast Louisiana and southern Mississippi. On the morning of Sunday, August 28, Katrina was upgraded to a top-notched Category 5 hurricane. Around 10 am, Mayor Nagin issued a mandatory evacuation of the entire city, the first such order ever issued in the city's history. An estimated 1 million people evacuated from Greater New Orleans and nearby areas before the storm. However, some 20% of New Orleans residents were still in the city when the storm hit. This included people who refused to leave home, those who felt their homes were adequate shelter from the storm, and people without cars or without financial means to leave. Some took refuge in the Superdome, which was designated as a "shelter of last resort" for those who could not leave.

The eye of the storm missed the heart of the city by only 20–30 miles, and strong winds ravaged the city, shattering windows, spreading debris in many areas, and bringing heavy rains and flooding to many areas of the city.

The situation worsened when levees on four of the city's canals were breached. Storm surge was funneled in via the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet, which breached in multiple places. This surge also filled the Industrial Canal which breached either from the surge or the effects of being hit by a loose barge (the ING 4727). The London Avenue Canal and the 17th Street Canal were breached by the elevated waters of Lake Pontchartrain. Some areas that initially seemed to suffer little from the storm found themselves flooded by rapidly rising water on August 30. As much as 80% of the city—parts of which are below sea level and much of which is only a few feet above—was flooded, with water reaching a depth of 25 feet (7.6 m) in some areas. Water levels were similar to those of the 1909 hurricane; but since many areas that were swamp or farmland in 1909 had become heavily settled, the effects were massively worse. The most recent estimates of the damage from the storm, by several insurance companies, are $10 to 25 billion, while the total economic loss from the disaster has been estimated at $100 billion. Hurricane Katrina surpassed Hurricane Andrew as the costliest hurricane in United States history.

The final death toll of Hurricane Katrina was 1,836 lives lost, primarily from Louisiana (1,577). Half of these were senior citizens.

On September 22, already devastated by Hurricane Katrina, the Industrial Canal in New Orleans was again flooded by Hurricane Rita as the recently-and-hurriedly-repaired levees were breached once more. Residents of Cameron Parish, Calcasieu Parish, and parts of Jefferson Davis Parish, Acadia Parish, Iberia Parish, Beauregard Parish, and Vermillion Parish were told to evacuate ahead of the storm. Cameron Parish was hit the hardest with the towns of Creole, Cameron, Grand Chenier, Johnson Bayou, and Holly Beach being totally demolished. Records around the Hackberry area show that wind gusts reached over 180 mph at a boat tied up to a dock. The people were told to be evacuated by Thursday, September 22, 2005 by 6:00 pm. Two days later, parish officials returned to the Gibbstown Bridge that crosses the Intracoastal Canal into Lower Cameron Parish. No one was known to be left in the parish as of that time on Thursday, September 22, 2005.

It only became clear with investigations in the months after Katrina that flooding in the majority of the city was not directly due to the storm being more powerful than the city's defenses. Rather, it was caused by what investigators termed "the costliest engineering mistake in American history". The United States Army Corps of Engineers designed the levee and floodwall system incorrectly, and contractors failed to build the system in places to the requirements of the Corps of Engineers' contracts. The Orleans Levee Board made only minimal perfunctory efforts in their assigned task of inspecting the city's vital defenses. Legal investigations of criminal negligence are pending.

Recovery

While many residents and businesses returned to the task of rebuilding the city, the effects of the hurricane on the economy and demographics of the city are expected to be dramatic and long term. As of March 2006, more than half of New Orleanians had yet to return to the city, and there were doubts as to how many more would. By 2008, estimated repopulation had topped 330,000.

In 2010 Louisiana Lieutenant Governor Mitch Landrieu won the mayor's race over 10 other candidates with some 66% of the vote on the first round, with widespread support across racial, demographic, and neighborhood boundaries.

Population

- -- City (343,829) - 2012 census

- -- Metro (1,167,764) - 2012 census

Economy

Arenas

- The Super Dome

Attractions

- Bourbon Street by Night

Bars and Clubs

- -- Club Ampersand

- -- Club Blue

- -- The Lamp Light -- A wild and raunchy strip club on Bourbon Street that occasionally closes its doors for Kindred only affairs.

- -- The Twilight Club -- A Kindred Gathering Place (Elysium)

- -- Tornado Strip-Club

Cemeteries

- -- Cypress Grove Cemetery

- -- Gates of Prayer Cemetery No.1

- -- Gates of Prayer Cemetery No.2

- -- Greenwood Cemetery

- -- Hebrew Rest Cemetery

- -- Holt Cemetery

- -- Lafayette Cemetery No.1

- -- Masonic Cemetery

- -- St. Louis Cemetery No.1 -- The city's most famous cemetery

- -- St. Louis Cemetery No.2

- -- St. Louis Cemetery No.3

- -- St. Patrick's Cemetery No.1

- -- St. Patrick's Cemetery No.2

- -- St. Patrick's Cemetery No.3

- -- St. Roch Cemetery

City Government

Crime

Citizens of New Orleans

- -- Diane Cloutier -- dead socialite

- -- Charlie Grisham -- (The witness to disaster)

- -- Lanee Andrin -- (bounty Hunter)

- -- Lance Pertkin - (private detective)

- -- Martin D'Richet - (mage)

- -- Michael Zyers - (petty theif)

- -- Toinette Thibault - Gallery Owner

- -- Mattie Tyler - Irish fight promoter / former fighter

- -- Anastacia Méndez

- -- Rainier Rogerson

- -- Rosalina Quigg

- -- Pedro Villaverde

- -- Lesley Verity

- -- Laurent Sims

- -- Maci Deniaud

- -- Sherwood Blue - owner of Club Blue

- -- Darcey Masson

- -- Brock Flores

- -- Lyn Winfield

- -- Amyas Mounce

- -- Thomasina Banderas

- -- Baltasar Harman

- -- Jodi Lopez

- -- Peyton Belcher - woman

- -- Laz Winter - Owner of the Tornado Strip-Club

- -- Grooveride Freenik - female hippie shop owner

- -- Newtgut Toadsmoke - warlock shop owner

- -- Flittercloud Gentleeyes - fay transgender shop owner

- -- Lucian Sammael - Goth

- -- Danger Muscles Masterson - female wrestler

- -- Notorious-D Dr Rhymes - local rapper

- -- Ke'toyaah Ryder - young black woman

- -- Tiereeque Howe - young black man

- -- Lahtifa Randal

- -- H.S. Howard - Hillbilly Crooner

- -- Steffunnie Maciver

- -- Lookus Batts - Elderly black man (Carriage Driver)

- -- Margahrette Elwin

- -- Jayrehl Faulkner - Falkner Leather Goods

- -- Joshonda Whitaker

- -- Wyleeum Wyman

- -- Betty Norton -- FAS3 Chief of Operations.

Current Events

Festivals

- -- Mardi Gras: To many people, Mardi Gras is New Orleans. The highlight of Carnival, Mardi Gras caps off almost two months of wild parties and complete abandon. Carnival refers to an entire season that begins on January 6th and ends on Mari Gras with raucous parties throughout the city and parades organized by private clubs (krewes).

Both the mortal and Kindred populations swell to incredible numbers during this time. Vampires from around the world flood the city, adding their own unique touches to the manic celebrations that grip New Orleans. This is the only time Prince Marcel looks the other way when vampires fail to Present themselves, but his spy network does overtime keeping track of the newcomers. None are allowed to stay after Mardi Gras is over. Still, there are few parties in the world like Mardi Gras, and the Kindred take full advantage of this time. Marcel himself hosts several parties, some open to any vampire. Elders and anarchs alike roam the streets, mingling freely with the multitudes of kine and feeling more alive than they do at any other time.

Galleries

- -- Thibault Studio -- A famous art gallery.

Haunted Houses

Holy Ground

Academy Of The Sacred Heart Chapel

Annunciation Catholic Church

Annunciation Episcopal Church

Baptist Theological Seminary Chapel

Berean Presbyterian Church

Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church

Blessed Seelos Catholic Church (formerly called St. Vincent dePaul)

Broad Street Mission Church

Cabrini High School and Chapel

Canal Street Presbyterian Church

Carrollton Avenue Church Of Christ

Carrollton Presbyterian Church

Carrollton United Methodist Church

The Center For Jesus The Lord (formerly Carmelite Convent)

Chapel Of The Holy Comforter-Anglican/Episcopal

Christ Church Cathedral

Christian Bible Fellowship (Building was formerly Redeemer Lutheran Church)

Church Of Christ in Eastern New Orleans

Church Of The Annunciation (Episcopal)

Coliseum Place Baptist Church

Congregation Agudath Achim Anshe Sfard

Congregation Beth Israel

Corpus Christi Catholic Church

Edgewater Baptist Church

Epiphany, Church Of The (Catholic)

Felicity United Methodist Church

Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church

First African Baptist Church

First African Baptist Church-Sixth District

First Baptist Church, New Orleans, LA.

First Church Of Christ Scientist

First Emanuel Baptist Church

First English Lutheran Church

First United Methodist Church (merged with Grace United Methodist Church 2008)

First Presbyterian Church

First Street United Methodist Church

First Universalist Unitarian Church

Fourth Church Of Christ Scientist

Gentilly Baptist Church

Gentilly Presbyterian Church

Gloria Dei Lutheran Church

Grace Episcopal Church

Grace Lutheran Church (present location)

Grace United Methodist Church (merged with First United Methodist Church effective 2008)

Greater Saint Stephen Full Gospel Church

Greek Orthodox Cathedral Of The Holy Trinity

Holy Angels Academy Chapel (Now converted to senior housing center)

Holy Ghost Catholic Church, New Orleans

Holy Name Of Jesus Catholic Church

Holy Rosary (Our Lady of the Holy Rosary) Catholic Church

Holy Trinity Catholic Church (closed)

Immaculate Conception (known locally as 'Jesuits' on Baronne')

Immanuel Evangelical Lutheran Church (building now owned by Victory Fellowship

Incarnate Word Catholic Church

Jah Center for Positive Change (see Mt. Calvary Lutheran Church below)

Korean Presbyterian Church of New Orleans

LaHarpe Community United Methodist Church

Lakeview Baptist Church (NOW CALLED SOJOURN)

Lakeview Presbyterian Church

Lake Vista United Methodist Church

Mater Dolorosa Catholic Church

Milne Boys Home Chapel

Mount Calvary Fellowship

Mount Calvary Lutheran Church (see Jah Center For Positive Change)

Mount Tabor Baptist Church

Mount Zion United Methodist Church

Napoleon Avenue Methodist Church

New Orleans Community Church

Norwegian Seamen's Church

Notre Dame Catholic Seminary

Our Lady of Good Counsel Catholic Church

Our Lady of Guadeloupe Catholic Church

Our Lady of Lavang Catholic Church

Our Lady Of Lourdes Catholic Church

Our Lady Of Prompt Succor

Our Lady Of The Sacred Heart /St. Boniface

Our Lady Star Of The Sea Catholic Church

Original Saint Ann's Church and Shrine

Original Saint Joseph Academy and Convent

Parker Memorial Methodist Church

Payne Memorial AME Church

Peace Church (Presbyterian)

Pilgrim Progress Missionary Baptist Church

Prince Of Peace Lutheran Church

Rayne Memorial United Methodist Church

Redeemer Presbyterian Church (sharing space with St. Charles Ave. Baptist Church)

Resurrection Of Our Lord Catholic Church

Sacred Heart of Jesus Church

Saint Alphonsus Community Center

Saint Andrew Episcopal Church

Saint Anna's Episcopal Church

Saint. Anthony Of Padua Catholic Church

Saint. Augustine Catholic Church

Saint Cecilia Church (Now closed)

Saint Charles Avenue Baptist Church

Saint Charles Avenue Church Of Christ

Saint Charles Presbyterian Church

Saint Clare's Monastery

Saint David Catholic Church

Saint. Dominic Catholic Church

Saint Francis de Sales Catholic Church

Saint. Francis Of Assisi Catholic Church

Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini Catholic Church

Saint Gabriel The Archangel Catholic Church

Saint George's Episcopal Church

Saint Henry's Catholic Church

Saint James African Methodist Church

Saint James Major Catholic Church

Saint Joan Of Arc Catholic Church

Saint John Lutheran Church

Saint John The Baptist Catholic Church

Saint. Joseph's Catholic Church (Tulane Avenue)

Saint. Leo The Great Catholic Church

Saint Louis Cathedral, New Orleans

Saint Luke Anglican Episcopal Church (Original Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church)

Saint Luke United Methodist Church

Saint Maria Goretti Catholic Church

Saint Mark Coptic Orthodox Church

Saint Mark's Methodist Church of the Vieux Carre

Saint Mary Of The Angels Catholic Church

Saint Mary's Assumption Catholic Church

Saint Mary's Catholic Chapel

Saint Mary's Italian Church (Old Ursuline Chapel)

Saint Mathew Evangelical Lutheran Church

Saint Matthew United Church Of Christ

Saint Matthias Catholic Church

Saint Maurice Catholic Church

Saint Monica Catholic Church

Saint. Patrick Catholic Church

Saint Paul's Episcopal Church

Saint Paul Lutheran Church

Saint Paul The Apostle Catholic Church

Saint Peter A.M.E.

Saint Peter Baptist Church

Saint Peter and Paul Catholic Church (Closed 2001)

Saint Peter Claver Catholic Church

Saint Pius X Catholic Church

Saint Raphael The Archangel Catholic Church (see also Transfiguration Catholic Church below)

Saint Rita of Cascia Catholic Church

Saint. Roch Cemetery Chapel

Saint. Rose Of Lima Catholic Church

Saint. Stephen Catholic Church

Saint Theresa Of Avila Catholic Church

Saint Theresa Little Flower of the Child Jesus Catholic Church

Saint Vincent De Paul Catholic Church (Renamed St. Francis Seelos Church)

Salem United Church Of Christ

Second Baptist Church Sixth District

Second Free Mission Baptist Church

Second Mount Olive Baptist Church

Sixth Baptist Church

Sojourn Church (formerly Lakeview Baptist Church)

Suburban Baptist Church

Temple Sinai Jewish Reform Congregation

The Way Christian Church

Third Presbyterian Church, New Orleans (closed August 1, 2004)

Transfiguration Catholic Church, New Orleans (this parish replaces St. Raphael the Archangel and also St. Francis Xavier Cabrini)

Trinity Episcopal Church

Trinity United Methodist Church

Touro Synagogue

Union Bethel AME Church

Unitarian Universalist Church and Community Center

Valence Street Baptist Church

Watson Memorial Teaching Ministries (building was Napoleon Ave Presbyterian Church)

Zion Lutheran Church

Hospitals

Hotels & Hostels

- -- Hotel St.Germaine -- This nineteenth century hotel on Bourbon St is Kindred friendly and is frequently visited by transient vampires.

Landmarks

Les Gens Des Ténèbres

Monasteries

Monuments

Museums

- -- New Orleans Museum of Art - {NOMA}

- -- New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum

Parks

Periodicals

- -- The Times Picayune (newspaper)

Private Residences

- -- Rubis d'le Nuit -- The plantation home of the Prince Marcel Guilbeau.

- -- Chantry of New Orleans -- Located in the Garden District.

Restaurants

Schools

Shops

Theatres

Transportation

The Kithain of the City that Care Forgot

Crescent City Mages

New Orleans is home to two factions of mages: the De Sauveterre family of witches and the various Covens of the Quadroon Legacies. Both groups of mages claim sovereign rights over the significant mystical resources of the most occult city in North America. The histories of the covens and the witch family date back to the founding of the city and their struggles over the magically rich environment of New Orleans have played out against the historically rich backdrop of the city's past. Indeed, the history of New Orleans is tightly interwoven with the struggle between these two groups of mages and their successes and failures have set the tone for each era of the city's history.

To say that these two factions are the only mages in New Orleans would be fatuous, but they have dominated the occult scene in New Orleans since the city's founding in 1718. The mages of the Traditions certainly visit the city on a regular basis and the Technocracy has established at least a foothold within the financial district of New Orleans. For reasons unknown, the city occasionally attracts the unwholesome attentions of the occasional Marauder and the infernal influences of the Nephandi can occasionally be felt by the city's more sensitive residents. Perhaps the most powerful competition that the De Sauveterre Family and the Quadroon Legacy face are the growing numbers of Hollow Ones who seem to be drawn to the city like flies to a bloated corpse.

Covens of the Quadroon Legacy

- -- Benoîte Glaisyer -- Voodoo Queen of the Quadroon Legacy.

- -- Honorine Mariette --

- -- Rémy de Lyon --

The De Sauveterre Family

- -- Jeannot Philippe De Sauveterre --

- -- Madame Prudence De Sauveterre --

- -- Lucette De Sauveterre --

Les Gens Des Ténèbres: The Kindred of Nawlins

"Take me in your arms"

"Forgetting all you couldn't do today"

"Black celebration"

"I'll drink to that"

"Black celebration"

"Tonight."

-- Depeche Mode, "Black Celebration"

Introduction: New Orleans' Kindred population is never stable. At any given time, members of any given clan or bloodline may be in the city; vampires journey from around the world to enjoy "The City That Care Forgot." While the city does not normally suffer from over-population, there is some question as to the exact number of vampires who exist there. Because New Orleans is known as a refugee city, vampires regularly come and go. Some stay no more than a night or two; others stay for months without Presenting themselves to Prince Marcel.

The number depends entirely on whom one asks and can range anywhere from 20 to 200 during Mardi Gras. The vast majority of the Kindred population are "short-timers," staying the city for a week or so to a few months at most before moving on. As in any society, however, New Orleans has its mainstays. In New Orleans these are mostly elders or clan leaders, though there are a few others who seem to have gone out of their way to make their presence known.

Another reason the Kindred population fluctuates so much is the regular disappearances of newcomers. Most vampires do not speak of these disappearances, whether from ignorance, good taste or fear. Still, the disappearances continue to haunt the community. Some blame witch-hunters; others blame anarchs. The true answer includes both of these and more.

The Damned: Because of New Orleans status as a city open to almost any vampire, it is impossible to know exactly how many vampires reside in the city at any one time.

However, Prince Marcel's sophisticated espionage network allows him to keep a reasonably current census of the vampire population.

Almost twenty make the city their permanent home, at least that many more maintain havens there, and dozens more pass through as tourists or refugees.

Power Structures: Many outsiders have been impressed by the prince's nonchalant self-confidence. Indeed, he seems so sure of himself that he lets almost any vampires, with the exceptions of the Sabbat and the Followers of Set, into the city. Others see this trait as a weakness, suggesting that Marcel cannot bar these visitors. Cainites who subscribe to this view believe that Prince Marcel's nights are numbered, for too many factions currently struggle for control of the city. The most obvious ones are the Prince's Council, the anarchs, the mages, the Brujah and the Followers of Set; there are undoubtedly many others.

Several groups of were-creatures exist outside the city, amid the bayous and cypress forests. More knowledgeable Kindred are aware that at least two of these groups are at war, but few know any particulars. These vampires know that Lupines contests the city's boundaries and fight vampiric control of outlying areas. The fact that Black Spiral Dancers control much of the land outside the city means nothing to them.

Brujah

Brujah

New Orleans' Brujah follow a far more rigid hierarchy than do members of the clan in other cities. In the early 1950s, Dutch came to the city and established himself as the leading Brujah in New Orleans.

While few other Brujah have established themselves in the city, there are always at least a few transients.

Indeed, only Clan Toreador sends more visitors to New Orleans.

- -- Dutch -- Dutch is an Idealistic Brujah who leads his clan in the city of New Orleans. He is childer to the famous Anarch Jeremy MacNeil. - {Primogen}

- -- Jake Almerson -- Local Rabble-rouser

Caitiff

Caitiff

Innumerable Caitiff come to New Orleans, but few make the city their home. Most Caitiff soon realize that the city suffers under an even more rigid hierarchy than most cities do, and they seek greener pastures elsewhere.

- -- Raymond Carson -- Slaver & Refugee of New Orleans

Gangrel

Gangrel

Once one of the most powerful clans in the city, the Gangrel have been out of favor since the middle 1950s, and no new Gangrel has made her home in or near the city since 1955, when Doran was slain and and a Gangrel named as the assassin.

Indeed, even the clan's most significant accomplishment -- the treaty with the Lupines -- now seems suspect.

While Gangrel still visit the city, many do not present themselves to Marcel, and others leave shortly after arriving. Only Xaviar, the Gangrel Justicar, seems free from the associated guilt, but he has done little for the clan in New Orleans.

Giovanni

Giovanni

- -- Bernardino Marco Giovanni -- Local Capo

- -- Santuzza Ghiberti -- Recent necromantic expert assigned to New Orleans.

- -- Flaviano Putanesca -- Pretty boy enforcer.

Malkavian

Malkavian

Malkavians rarely stay in New Orleans for more than a few years. One was known to joke that New Orleans was already crazy enough, so why stay there?

Still, New Orleans attracts a good number of transient Malkavians, who stay for a little while until they tire of the city.

- -- Father Iago -- Father Iago currently known as Lazarus James. {Primogen}

- -- Uriah Travers -- Outcast Abomination

Nosferatu

Nosferatu

Nosferatu do not find New Orleans the most inviting of cities. It lacks subways, sewers, and all the other dank and moldy places clan members find most accommodating.

Those who have stayed in the city for any length of time have found it in their best interests to side with Prince Marcel, serving him as spies and lookouts.

Even newcomers quickly discover the advantages of doing so.

- -- Avery Meeks -- {Primogen} -- Sewer-rat Orphan

- -- Roger Meeks -- Confederate Spy & Mercenary Information Broker

- -- Martin Meeks -- Head of Prince Marcel's Spy Network

Toreador

Toreador

To outside observers, New Orleans is Toreador heaven, and this accounts for the large number of Toreador who come to the city for a short time. While few seek permanent havens in the city, Toreador often visit it, if only for a few nights at a time.

Many Toreador can be found sitting in with the jazz bands or among the crowds in the French Quarter. The clan is loosely organized in the city, but newcomers always seem to have a fairly good idea of where other clan members can be found.

- -- Morgaine -- {Primogen}

- -- Julia Cammeron -- Runaway Pet

- -- Josua Cambridge -- Neonate Artiste

Tremere

Tremere

The Tremere of New Orleans make up one of the most powerful, yet least respected chantries in North America. An odd collection of misfits have settled here, and the Kindred of New Orleans debate their effectiveness.