Rome -- medieval

Quote

Appearance

Climate

Rome has a Mediterranean climate, with cool, humid winters and warm, dry summers.

Its average annual temperature is above (68 °F) during the day and (50 °F) at night. In the coldest month – January, the average temperature is (54 °F) during the day and (37 °F) at night. In the warmest months – July and August, the average temperature is (86 °F) during the day and (64 °F) at night.

December, January and February are the coldest months, with a daily mean temperature of (46 °F). Temperatures during these months generally vary between (50 and 59 °F) during the day and between (37 and 41 °F) at night, with colder or warmer spells occurring frequently. Snowfall is rare but not unheard of, with light snow or flurries occurring almost every winter, generally without accumulation, and major snowfalls approximately once every 5 years.

The average relative humidity is 75%, varying from 72% in July to 77% in November. Sea temperatures vary from a low of (55 °F) in February and March to a high of (75 °F) in August

Economy

Pilgrimage

Rome has been a major Christian pilgrimage site since the Middle Ages. People from all over the Christian world visit Vatican City, within the city of Rome, the seat of the papacy. The Pope was the most influential figure during the Middle Ages. The city became a major pilgrimage site during the Middle Ages and the focus of struggles between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire starting with Charlemagne, who was crowned its first emperor in Rome in 800 by Pope Leo III. Apart from brief periods as an independent city during the Middle Ages, Rome kept its status as Papal capital and "holy city" for centuries, even when the Papacy briefly relocated to Avignon (1309–1377). Catholics believe that the Vatican is the last resting place of St. Peter.

Pilgrimages to Rome can involve visits to a large number of sites, both within Vatican City and in Italian territory. A popular stopping point is the Pilate's stairs: these are, according to the Christian tradition, the steps that led up to the praetorium of Pontius Pilate in Jerusalem, which Jesus Christ stood on during his Passion on his way to trial.[91] The stairs were, reputedly, brought to Rome by St. Helena in the 4th Century. For centuries, the Scala Santa has attracted Christian pilgrims who wished to honour the Passion of Jesus. Object of pilgrimage are also several catacombs built in the Roman age, in which Christians prayed, buried their dead and performed worship during periods of persecution, and various national churches (among them San Luigi dei francesi and Santa Maria dell'Anima), or churches associated with individual religious orders, such as the Jesuit Churches of Jesus and Sant'Ignazio.

Traditionally, pilgrims in Rome and Roman citizens thanking God for a grace should visit by foot the seven pilgrim churches (Italian: Le sette chiese) in 24 hours. This custom, mandatory for each pilgrim in the Middle Ages, was codified in the 16th century by Saint Philip Neri. The seven churches are the four major Basilicas (St Peter in Vatican, St Paul outside the Walls, St John in Lateran and Santa Maria Maggiore), while the other three are San Lorenzo fuori le mura (a palaeochristian Basilica), Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (a church founded by Helena, the mother of Constantine, which hosts fragments of wood attributed to the holy cross) and San Sebastiano fuori le mura (which lies on the Appian Way and is built above Roman catacombs).

Geography

[[]]

Rome is in the Lazio region of central Italy on the Tiber (Italian: Tevere) river. The original settlement developed on hills that faced onto a ford beside the Tiber Island, the only natural ford of the river in this area. The Rome of the Kings was built on seven hills: the Aventine Hill, the Caelian Hill, the Capitoline Hill, the Esquiline Hill, the Palatine Hill, the Quirinal Hill, and the Viminal Hill. Modern Rome is also crossed by another river, the Aniene, which flows into the Tiber north of the historic centre.

Although the city centre is about 24 kilometres (15 mi) inland from the Tyrrhenian Sea, the city territory extends to the shore, where the south-western district of Ostia is located.

Throughout the history of Rome, the urban limits of the city were considered to be the area within the city’s walls. Originally, these consisted of the Servian Wall, which was built twelve years after the Gaulish sack of the city in 390 BC. This contained most of the Esquiline and Caelian hills, as well as the whole of the other five. Rome outgrew the Servian Wall, but no more walls were constructed until almost 700 years later, when, in 270 AD, Emperor Aurelian began building the Aurelian Walls. These were almost 19 kilometres (12 mi) long, and were still the walls the troops of the Kingdom of Italy had to breach to enter the city in 1870.

History

Timeline

- 1084 - The city of Rome is attacked by the Normans.

- The Sack of Rome of May 1084 was a Norman sack, the result of the pope's call for aid from the duke of Apulia, Robert Guiscard. Pope Gregory VII was besieged in the Castel Sant'Angelo by the Emperor Henry IV in June 1083. He held out and called for aid from Guiscard, who was then fighting the Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus in the Balkans. He returned, however, to the Italian Peninsula and marched north with 36,000 men. He entered Rome and forced Henry to retire, but a riot of the citizens led to a three days sack, after which Guiscard escorted the pope to the Lateran. The Normans had mainly pillaged the old city, which was then one of the richest cities in Italy. After days of unending violence, the Romans rose up causing the Normans to set fire to the city. Many of the buildings of Rome were gutted on the Capitol and Palatine hills along with the area between the Colosseum and the Lateran. In the end the ravaged Roman populace succumbed to the Normans.

- 1108 - The church of San Clemente is in this year rebuilt.

- 1140 - The church of Santa Maria in Trastevere is restored.

- 1200 - The city becomes an independent commune

- 1232 - The cloisters in the Basilica of St. John Lateran are finished.

- 1300 - Pope Boniface VIII proclaims the First Holy Year.

- 1309 - The Papacy is moved to Avignon under Pope Clement V

- 1347 - The patriot and rebel Cola di Rienzo tries to restore the Roman Republic.

- 1348 - As in most of Europe, the Black Death strikes Rome.

- 1084 - The city of Rome is attacked by the Normans.

Imperial Rome: Foundations of the Dark Medieval

The Early Empire

By the end of the Republic, the city of Rome had achieved a grandeur befitting the capital of an empire dominating the whole of the Mediterranean. It was, at the time, the largest city in the world. Estimates of its peak population range from 450,000 to over 3.5 million people with estimates of 1 to 2 million being most popular with historians. This grandeur increased under Augustus, who completed Caesar's projects and added many of his own, such as the Forum of Augustus and the Ara Pacis. He is said to have remarked that he found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble (Urbem latericium invenit, marmoream reliquit). Augustus's successors sought to emulate his success in part by adding their own contributions to the city. In AD 64, during the reign of Nero, the Great Fire of Rome left much of the city destroyed, but in many ways it was used as an excuse for new development.

Rome was a subsidized city at the time, with roughly 15 to 25 percent of its grain supply being paid by the central government. Commerce and industry played a smaller role compared to that of other cities like Alexandria. This meant that Rome had to depend upon goods and production from other parts of the Empire to sustain such a large population. This was mostly paid by taxes that were levied by the Roman government. If it had not been subsidized, Rome would have been significantly smaller.

Rome's population declined after its peak in the 2nd century. At the end of that century, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the Antonine Plague killed 2,000 people a day. Marcus Aurelius died in 180, his reign being the last of the "Five Good Emperors" and the Pax Romana. His son Commodus, who had been co-emperor since AD 177, assumed full imperial power, which is most generally associated with the gradual decline of the Western Roman Empire. Rome's population was only a fraction of its peak when the Aurelian Wall was completed in the year 273 (in that year its population was only around 500,000).

The Crisis of the Third Century

Starting in the early 3rd century, matters changed. The "Crisis of the third century" defines the disasters and political troubles for the Empire, which nearly collapsed. The new feeling of danger and the menace of barbarian invasions was clearly shown by the decision of Emperor Aurelian, who at year 273 finished encircling the capital itself with a massive wall which had a perimeter that measured close to 20 km (12 mi). Rome formally remained capital of the empire, but emperors spent less and less time there. At the end of 3rd century Diocletian's political reforms, Rome was deprived of its traditional role of administrative capital of the Empire. Later, western emperors ruled from Milan or Ravenna, or cities in Gaul. In 330, Constantine I established a second capital at Constantinople. At this time, part of the Roman aristocratic class moved to this new center, followed by many of the artists and craftsmen who were living in the city.

The Rise of Christianity

Christianity reached Rome during the 1st century AD. For the first two centuries of the Christian era, Imperial authorities largely viewed Christianity simply as a Jewish sect rather than a distinct religion. No emperor issued general laws against the faith or its Church, and persecutions, such as they were, were carried out under the authority of local government officials. A surviving letter from Pliny the Younger, governor of Bythinia, to the emperor Trajan describes his persecution and executions of Christians; Trajan notably responded that Pliny should not seek out Christians nor heed anonymous denunciations, but only punish open Christians who refused to recant.

Suetonius mentions in passing that during the reign of Nero "punishment was inflicted on the Christians, a class of men given to a new and mischievous superstition" (superstitionis novae ac maleficae). He gives no reason for the punishment. Tacitus reports that after the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64, some among the population held Nero responsible and that the emperor attempted to deflect blame onto the Christians. The war against the Jews during Nero's reign, which so destabilized the empire that it led to civil war and Nero's suicide, provided an additional rationale for suppression of this 'Jewish' sect.

Diocletian undertook what was to be the most severe and last major persecution of Christians, lasting from 303 to 311. Christianity had become too widespread to suppress, and in 313, the Edict of Milan made tolerance the official policy. Constantine I (sole ruler 324–337) became the first Christian emperor, and in 380 Theodosius I established Christianity as the official religion.

Under Theodosius, visits to the pagan temples were forbidden, the eternal fire in the Temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum extinguished, the Vestal Virgins disbanded, auspices and witch-crafting punished. Theodosius refused to restore the Altar of Victory in the Senate House, as asked by remaining pagan Senators.

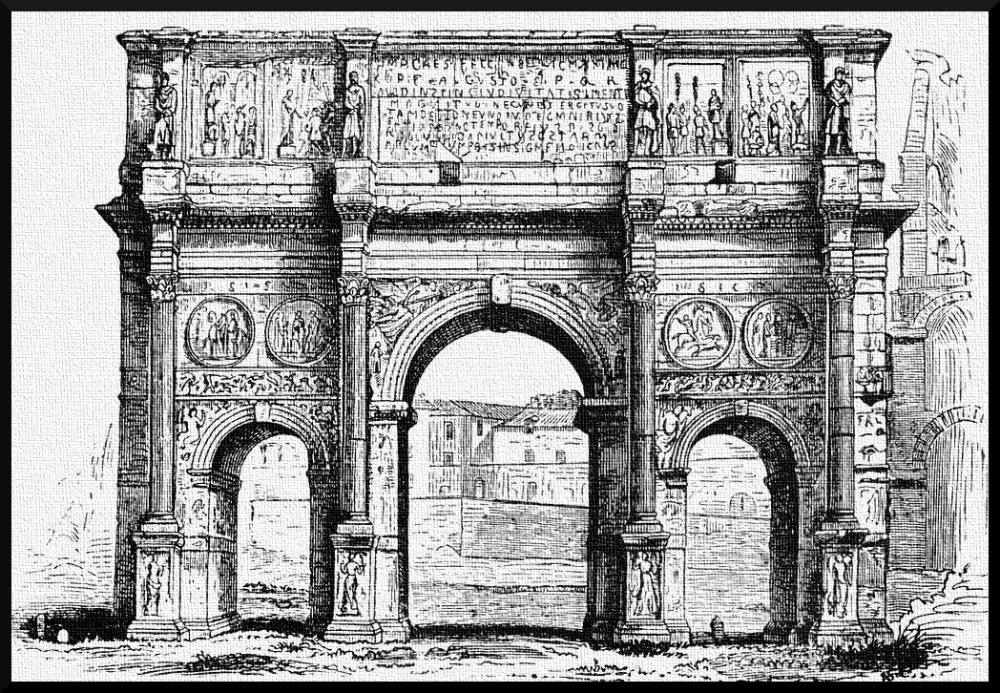

The Empire's conversion to Christianity made the Bishop of Rome (later called the Pope) the senior religious figure in the Western Empire, as officially stated in 380 by the Edict of Thessalonica. In spite of its increasingly marginal role in the Empire, Rome retained its historic prestige, and this period saw the last wave of construction activity: Constantine's predecessor Maxentius built buildings such as its basilica in the Forum, Constantine himself erected the Arch of Constantine to celebrate his victory over the former, and Diocletian built the greatest baths of all. Constantine was also the first patron of official Christian buildings in the city. He donated the Lateran Palace to the Pope, and built the first great basilica, the old St. Peter's Basilica.

The Germanic invasions and collapse of the Western Empire

Still Rome remained one of the strongholds of Paganism, led by the aristocrats and senators. However, the new walls did not stop the city being sacked first by Alaric on 24 August, 410, by Geiseric in 455 and even by general Ricimer's unpaid Roman troops (largely composed of barbarians) on 11 July, 472. This was the first time in almost 800 years that Rome had fallen to an enemy. The previous sack of Rome had been accomplished by the Gauls under their leader Brennus in 387 BC. The sacking of 410 is seen as a major landmark in the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire. St. Jerome, living in Bethlehem at the time, wrote that "The City which had taken the whole world was itself taken." These sackings of the city astonished all the Roman world. In any case, the damage caused by the sackings may have been overestimated. The population already started to decline from the late 4th century onward, although around the middle of the fifth century it seems that Rome continued to be the most populous city of the two parts of the Empire, with a population of not less than 650,000 inhabitants. The decline greatly accelerated following the capture of Africa Proconsularis by the Vandals. Many inhabitants now fled as the city no longer could be supplied with grain from Africa from the mid-5th century onward.

At the beginning of the 6th century Rome's population may have been less than 100,000. Many monuments were being destroyed by the citizens themselves, who stripped stones from closed temples and other precious buildings, and even burned statues to make lime for their personal use. In addition, most of the increasing number of churches were built in this way. For example, the first Saint Peter's Basilica was erected using spoils from the abandoned Circus of Nero. This "self-eating" attitude was a constant feature of Rome until the Renaissance. From the 4th century, imperial edicts against stripping of stones and especially marble were common, but the need for their repetition shows that they were ineffective. Sometimes new churches were created by simply taking advantage of early Pagan temples, while sometimes changing the Pagan god or hero to a corresponding Christian saint or martyr. In this way, the Temple of Romulus and Remus became the basilica of the twin saints Cosmas and Damian. Later, the Pantheon, Temple of All Gods, became the church of All Martyrs.

The Rule of the Barbarians and Byzantines

In 480, the last Western Roman emperor, Julius Nepos, was murdered and a Roman general of barbarian origin, Odoacer, declared allegiance to Eastern Roman emperor Zeno. Despite owing nominal allegiance to Constantinople, Odoacer and later the Ostrogoths continued, like the last emperors, to rule Italy as a virtually independent realm from Ravenna. Meanwhile, the Senate, even though long since stripped of wider powers, continued to administer Rome itself, with the Pope usually coming from a senatorial family. This situation continued until Theodahad murdered Amalasuntha, a pro-imperial Gothic queen, and usurped the power in 535. The Eastern Roman emperor, Justinian I (reigned 527–565), used this as a pretext to send forces to Italy under his famed general Belisarius, recapturing the city next year. The Byzantines successfully defended the city in a year-long siege, and eventually took Ravenna.

Gothic resistance revived however, and on 17 December, 546, the Ostrogoths under Totila recaptured and sacked Rome. Belisarius soon recovered the city, but the Ostrogoths retook it in 549. Belisarius was replaced by Narses, who captured Rome from the Ostrogoths for good in 552, ending the so-called Gothic Wars which had devastated much of Italy. The continual war around Rome in the 530s and 540s left it in a state of total disrepair — near-abandoned and desolate with much of its lower-lying parts turned into unhealthy marshes as the drainage systems were neglected and the Tiber's embankments fell into disrepair in the course of the latter half of the 6th century. Here, malaria developed. The aqueducts were never repaired, leading to a shrinking population of less than 50,000 concentrated near the Tiber and around the Campus Martius, abandoning those districts without water supply. There is a legend, significant though untrue, that there was a moment where no one remained living in Rome.

Justinian I tried to grant Rome subsidies for the maintenance of public buildings, aqueducts and bridges — though, being mostly drawn from an Italy dramatically impoverished by the recent wars, these were not always sufficient. He also styled himself the patron of its remaining scholars, orators, physicians and lawyers in the stated hope that eventually more youths would seek a better education. After the wars, the Senate was theoretically restored, but under the supervision of the urban prefect and other officials appointed by, and responsible to, the Byzantine authorities in Ravenna.

However, the Pope was now one of the leading religious figures in the entire Byzantine Empire and effectively more powerful locally than either the remaining senators or local Byzantine officials. In practice, local power in Rome devolved to the Pope and, over the next few decades, both much of the remaining possessions of the senatorial aristocracy and the local Byzantine administration in Rome were absorbed by the Church.

The reign of Justinian's nephew and successor Justin II (reigned 565–578) was marked from the Italian point of view by the invasion of the Lombards under Alboin (568). In capturing the regions of Benevento, Lombardy, Piedmont, Spoleto and Tuscany, the invaders effectively restricted Imperial authority to small islands of land surrounding a number of coastal cities, including Ravenna, Naples, Rome and the area of the future Venice. The one inland city continuing under Byzantine control was Perugia, which provided a repeatedly threatened overland link between Rome and Ravenna. In 578 and again in 580, the Senate, in some of its last recorded acts, had to ask for the support of Tiberius II Constantine (reigned 578–582) against the approaching Dukes, Faroald I of Spoleto and Zotto of Benevento.

Maurice (reigned 582–602) added a new factor in the continuing conflict by creating an alliance with Childebert II of Austrasia (reigned 575–595). The armies of the Frankish King invaded the Lombard territories in 584, 585, 588 and 590. Rome had suffered badly from a disastrous flood of the Tiber in 589, followed by a plague in 590. The latter is notable for the legend of the angel seen, while the newly elected Pope Gregory I (term 590–604) was passing in procession by Hadrian's Tomb, to hover over the building and to sheathe his flaming sword as a sign that the pestilence was about to cease. The city was safe from capture at least.

Agilulf, however, the new Lombard King (reigned 591 to c. 616), managed to secure peace with Childebert, reorganized his territories and resumed activities against both Naples and Rome by 592. With the Emperor preoccupied with wars in the eastern borders and the various succeeding Exarchs unable to secure Rome from invasion, Gregory took personal initiative in starting negotiations for a peace treaty. This was completed in the autumn of 598—later recognized by Maurice—lasting until the end of his reign.

The position of the Bishop of Rome was further strengthened under the usurper Phocas (reigned 602–610). Phocas recognized his primacy over that of the Patriarch of Constantinople and even decreed Pope Boniface III (607) to be "the head of all the Churches". Phocas's reign saw the erection of the last imperial monument in the Roman Forum, the column bearing his name. He also gave the Pope the Pantheon, at the time closed for centuries, and thus probably saved it from destruction.

During the 7th century, an influx of both Byzantine officials and churchmen from elsewhere in the empire made both the local lay aristocracy and Church leadership largely Greek speaking. However, the strong Byzantine cultural influence did not always lead to political harmony between Rome and Constantinople. In the controversy over Monothelitism, popes found themselves under severe pressure (sometimes amounting to physical force) when they failed to keep in step with Constantinople's shifting theological positions. In 653, Pope Martin I was deported to Constantinople and, after a show trial, exiled to the Crimea, where he died.

Then, in 663, Rome had its first imperial visit for two centuries, by Constans II — its worst disaster since the Gothic Wars when the Emperor proceeded to strip Rome of metal, including that from buildings and statues, to provide armament materials for use against the Saracens. However, for the next half century, despite further tensions, Rome and the Papacy continued to prefer continued Byzantine rule—in part because the alternative was Lombard rule, and in part because Rome's food was largely coming from Papal estates elsewhere in the Empire, particularly Sicily.

Medieval Rome

The Break with Byzantium and formation of the Papal States

Though seat of the papacy, condition that assured to the city a certain number of inhabitants, the population of Rome, that in the 4th century was estimated at about 500,000, soon underwent a precipitous decline. During the Middle Age, the built-up area shrank until Romans settlement was confined to the shore of the Tiber, where water was available. Only one of the ancient aqueducts was still operating. The decline was momentarily arrested under Pope Gregory I (590-604), whose pontificate signed the first step towards the temporal power of the Church. His work of conversation did not follow a despotic design, and eventually contributed to improve the contacts between Rome and the barbaric peoples. His papacy marked the foundation of medieval Rome, although not much is known about the city in this period since little archeological evidence has survived. For a while Italy underwent a period of peace but soon became a battleground again. In the 6th century, the possession of the city was still disputed by Goths and Byzantines. But in the 7th century Rome passed under the temporary protection of the popes, who ruled the city up until the 19th century, period in which the history of the papacy is intricately connected with the history of Rome. When Pope Stephen III was threatened by the Lombards, he appealed for help to Pepin, king of the Franks. He defeated the barbars and granted the Pope a portion of Lombard territory (754), marking the beginning of the temporal power of the popes over the States of the Church. The 25th of December 800, Pepin's son, Charlemagne, was crowned by Leo III in Saint Peter's as Augustus and Emperor. The Holy Roman Empire survived until the abdication of Francis II of Austria in 1806. The walls of the Leonine City, built to defend the Borgo and St Peter's, date from the 9th century. The strength of the papacy increased under Pope Nicholas I (858-67) but with his death the prestige of the popes declined and the German emperors took an active part in the papal elections throughout the 10th and early 11th centuries. Gregory VII (1073-85), helped by some Roman noble families, reasserted papal authority, but turned out to be unable to prevent the Norman Robert Guiscard from conquering Sicily and devasting Rome in 1084.

Current Events

Politics: Guelphs and Ghibelline?

The Guelphs and Ghibellines were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of central and northern Italy. During the 12th and 13th centuries, rivalry between these two parties formed a particularly important aspect of the internal politics of medieval Italy. The struggle for power between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire had arisen with the Investiture Controversy, which began in 1075 and ended with the Concordat of Worms in 1122. The division between the Guelphs and Ghibellines in Italy, however, fuelled by the imperial Great Interregnum, persisted until the 15th century.

History

Origins

Guelph (often spelled Guelf; in Italian Guelfo, plural Guelfi) is an Italian form of the name of the House of Welf, the family of the dukes of Bavaria (including the namesake Welf II, Duke of Bavaria, as well as Henry the Lion). The Welfs were said to have used the name as a rallying cry during the Siege of Weinsberg in 1140, in which the rival Hohenstaufens of Swabia (led by Conrad III of Germany) used "Wibellingen", the name of a castle today known as Waiblingen, as their cry; "Wibellingen" subsequently became Ghibellino in Italian.

The names were likely introduced to Italy during the reign of Frederick Barbarossa. When Frederick conducted military campaigns in Italy to expand imperial power there, his supporters became known as Ghibellines (Ghibellini). The Lombard League and its allies were defending the liberties of the urban communes against the Emperor's encroachments and became known as Guelphs (Guelfi).

The Ghibellines were thus the imperial party, while the Guelphs supported the Pope. Broadly speaking, Guelphs tended to come from wealthy mercantile families, whereas Ghibellines were predominantly those whose wealth was based on agricultural estates. Guelph cities tended to be in areas where the Emperor was more of a threat to local interests than the Pope, and Ghibelline cities tended to be in areas where the enlargement of the Papal States was the more immediate threat. The Lombard League defeated Frederick at the Battle of Legnano in 1176. Frederick recognized the full autonomy of the cities of the Lombard league under his nominal suzerainty.

The division developed its own dynamic in the politics of medieval Italy, and it persisted long after the direct confrontation between Emperor and Pope had ceased. Smaller cities tended to be Ghibelline if the larger city nearby was Guelph, as the Guelph Republic of Florence and Ghibelline Republic of Siena faced off at the Battle of Montaperti, 1260. Pisa maintained a staunch Ghibelline stance against her fiercest rivals, the Guelph Republic of Genoa and Florence. Adherence to one of the parties could therefore be motivated by local or regional political reasons. Within cities, party allegiances differed from guild to guild, rione to rione, and a city could easily change party after internal upheaval. Moreover, sometimes traditionally Ghibelline cities allied with the Papacy, while Guelph cities were even punished with interdict.

Contemporaries did not use the terms Guelph and Ghibellines much until about 1250, and then only in Tuscany (where they originated), with the names "church party" and "imperial party" preferred in some areas.

Population

- Annual Census, 1100 A.D.: 35,350

Citizens of Rome

Clergy

Craftsmen

- Pino Ajello {master gardener}

Criminals

- Triga Consortium -- A ruthless gang of thieves from the Campus Martius.

- Carmelo Acconci -- Spokesman for the gangs of the Trans-Tiberum

Merchants

- Tarquinius -- Scholar of Secrets

Nightwalkers

- Berenice Barzetti

- Daria Notoriano {young and attractive given to Tarqinius in payment}

- Nives Bellandini {skinny glutton}

Patriciate

- Annibaldi family -- The Annibaldi were a powerful baronal family of Rome and the Lazio in the Middle Ages.

- Caetani -- The Caetani, or Gaetani, is the name of an Italian noble family which played a great part in the history of Pisa and of Rome, principally via their close links to the papacy.

- Colonna family -- Also known as Sciarrillo or Sciarra, were an Italian noble family who held considerable influence during the Dark Ages to the Renaissance. {Ghibelline}

- Conti di Segni -- The Conti di Segni were an important noble family of medieval and early modern Italy originating in Segni, Lazio. Many members of the family acted as military commanders or ecclesiastical dignitaries. {*}

- Cremaschi family -- A family of cloth merchants whose mercantile success have propelled them into the dangerous arena of Roman politics.

- Crescentii family -- A powerful extended family of wealthy merchants who formerly controlled the popes of the 10th century.

- Frangipani family -- The Frangipani family is a powerful Roman patrician clan with strong Guelph sympathies.

- Mancini family -- The Mancini family of Rome traces its origins back to Lucius Hostilius Mancinus who was consul in 145 BC and a commander of the Roman fleet during the Third Punic War.

- Orsini family -- The Orsini family were one of the most influential princely families in medieval Italy and renaissance Rome. {Guelph faction}

- Pierleoni family -- The family of the Pierleoni, meaning "sons of Peter Leo", was a great Roman patrician clan of the Middle Ages, headquartered in a tower house in the Jewish quarter, Trastevere.

- Prefetti di Vico -- An Italian noble family, of German origin, who established in Rome from the 10th century.

- Theophylacti family -- The counts of Tusculum were the most powerful secular noblemen in Latium, near Rome, in the present-day Italy between the 10th and 12th centuries.

Senatus Populusque Romanus (city council)

Festivities

The Life of people during the Middle ages was dictated by the changes in the season. The different seasons and months of the year were celebrated with Religious Feasts and Festivals - the Middle Ages holidays. The religion of Christianity had been established in England during the Dark Ages. In the Middle Ages, following the Norman conquest, new stone churches and cathedrals were built. Middle Ages Holidays marked an event of religious importance for every month of the year. The rural population of the Middle Ages had their days of rest and amusement, Middle Ages holidays were then much more numerous than at present. At that period the festivals of the Church were frequent and rigidly kept, as each of them was the pretext for a forced holiday from manual labor.

- Twelfth Night (January) -- Religious festival and feasts celebrating the visit of the Wise Men, or Magi, following the birth of Jesus.

- St Valentine's Day (February) -- The Medieval festival celebrating love - singing, dancing and pairing games.

- Carnival (Late February - Early March) --

- Easter (March) -- Easter celebrated by the Mystery plays depicting the crucifixion.

- Lent (40 days)

- Ash Wednesday (start of Lent)

- Holy Week (last week of Lent before Easter)

- Good Friday (end of Lent)

- Easter Sunday

- All Fool's Day (April) -- The Jesters, or Lords of Misrule, took charge for the day and caused mayhem with jokes and jests!

- May Day (May) -- May Day was a spring festival celebrating May Day when a Queen of the May was chosen and villagers danced around the maypole.

- Midsummer Eve (June) -- Midsummer Eve, the Mummers entertained at the 'Festival of Fire' reliving legends such as St George and the Dragon. Bones were often burned leading to the term 'bonfire'. The summer Solstice was June 23rd.

- St. Swithin's Day (July) -- St. Swithin's Day falls on 15th July. Legend says that during the bones of St Swithin were moved and after the ceremony it began to rain and continued to do so for forty days.

- Lammas Day (August) -- Lammas Day was celebrated on August 2nd. The ' loaf-mass ' day, the festival of the first wheat harvest of the year. Houses were sometimes decorated with garlands and there were candle lit processions.

- Michaelmas (September) -- The 29th September was when Michaelmas celebrated the life of St Michael and the traditional food on Michaelmas was goose or chicken.

- St Crispin's Day (October) -- October 25th celebrating St Crispin's Day. Revels and bonfires and people acted as 'King Crispin' .

- All Souls Day (November) -- The Day of the Dead - All Souls Day or All Hallow's Day ( Halloween ) when revels were held and bonfires were lit.

- Christmas (December) -- December 25 is celebrated as the birthday of Christ.

Fortifications

Defensive walls are a feature of ancient Roman architecture. The Romans generally fortified cities, rather than fortresses, but there are some fortified camps, such as the Saxon Shore forts like Porchester Castle in England. City walls were already significant in Etruscan architecture, and in the struggle for control of Italy under the early Republic many more were built, using different techniques. These included tightly-fitting massive irregular polygonal blocks, shaped to fit exactly in a way reminiscent of later Inca work. The Romans called a simple rampart wall an agger; at this date great height was not necessary.

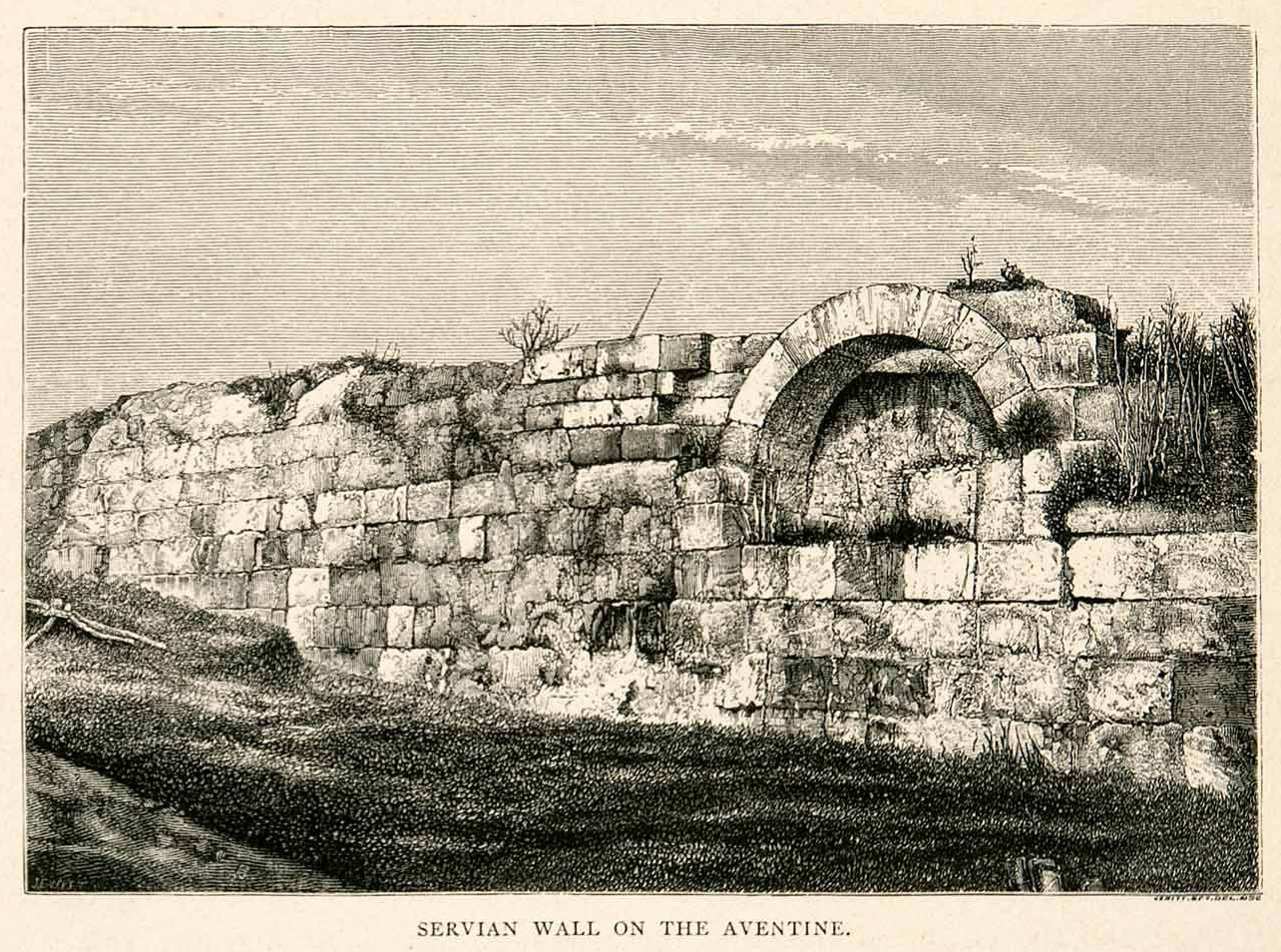

Servian Wall

The Servian Wall (outlined in blue) was an ancient Roman defensive barrier constructed around the city of Rome in the early 4th century BC. The wall was up to 10 metres (32.8 ft) in height in places, 3.6 metres (12 ft) wide at its base, 11 km (7 mi) long,[1] and is believed to have had 16 main gates, though many of these are mentioned only from writings, with no other known remains. By the 3rd century AD it was superseded by the construction of the larger Aurelian Walls.

History

It is presumed that the wall is named after the sixth Roman King, Servius Tullius. Although its outline may go back to the 6th century BC, the currently extant wall was, it is estimated, built during the early Roman Republic, possibly as a way to prevent a repeat of the sack of Rome after the Battle of the Allia by the Gauls of Brennus. Due to the ease with which the Gauls entered the city, it is conjectured[by whom?] that at some time previous to this, Rome had been forced by its Etruscan rulers to dismantle any significant prior defenses.

Construction

The wall was built from large blocks of tuff (a volcanic rock made from ash and rock fragments ejected during an eruption) quarried from the Grotta Oscura quarry near Rome's early rival Veii. In addition to the blocks, some sections of the structure incorporated a deep fossa, or ditch in front of it, as a means to effectively heighten the wall during attack from invaders.

Along part of its topographically weaker northern perimeter was an agger, a defensive ramp of earth heaped up to the wall along the inside. This thickened the wall, and also gave defenders a base to stand while repelling any attack. The wall was also outfitted with defensive war engines, including catapults.

Usage

The Servian Wall was formidable enough to repel Hannibal during the Second Punic War. Hannibal famously invaded Italy across the Alps with elephants, and had crushed several Roman armies in the early stages of the war. However, the wall was never put to the test as Hannibal only once, in 211 BC, brought his Carthaginian army to Rome as part of a feint to draw the Roman army from Capua. When it was clear that this had failed, he turned away, without approaching closer than 3 miles (5 km) to Rome, as a Roman army sallied out of the Servian walls and pitched a camp next to Hannibal's. During the Roman civil wars, the Servian walls were repeatedly overrun.

The wall was still maintained through the end of the Republic and in the early Empire. By this time, Rome had already begun to grow outside the original Servian Wall. The organization of Rome into regions under Augustus placed regions II, III, IV, VI, VIII, X, and XI within the Servian Wall, with the other sections outside of it.[citation needed]

The wall became unnecessary as Rome became well protected by the ever-expanding military strength of the Republic and of the later Empire. As the city continued to grow and prosper, it was essentially unwalled for the first three centuries of the Empire. When German tribes made further incursions along the Roman frontier in the 3rd century AD, Emperor Aurelian had the larger Aurelian Walls built to protect Rome.

Aurelian Walls

Introduction

The Aurelian Walls (Italian: Mura aureliane) are a line of city walls built between 271 AD and 275 AD in Rome, Italy, during the reign of the Roman Emperors Aurelian and Probus. They superseded the earlier Servian Wall built during the 4th century BC.

The walls enclosed all the seven hills of Rome plus the Campus Martius and, on the left bank of the Tiber, the Trastevere district. The river banks within the city limits appear to have been left unfortified, although they were fortified along the Campus Martius. The size of the entire enclosed area is 1,400 hectares (3,500 acres).

Construction

The full circuit ran for 19 kilometres (12 mi) surrounding an area of 13.7 square kilometres (5.3 sq mi). The walls were constructed in brick-faced concrete, 3.5 metres (11 ft) thick and 8 metres (26 ft) high, with a square tower every 100 Roman feet (29.6 metres (97 ft)).

In the 4th century, remodelling doubled the height of the walls to 16 metres (52 ft). By 500 AD, the circuit possessed 383 towers, 7,020 crenellations, 18 main gates, 5 postern gates, 116 latrines, and 2,066 large external windows.

History

By the third century AD, the boundaries of Rome had grown far beyond the area enclosed by the old Servian Wall, built during the Republican period in the late 4th century BC. Rome had remained unfortified during the subsequent centuries of expansion and consolidation due to lack of hostile threats against the city. The citizens of Rome took great pride in knowing that Rome required no fortifications because of the stability brought by the Pax Romana and the protection of the Roman Army. However, the need for updated defences became acute during the crisis of the Third Century, when barbarian tribes flooded through the Germanic frontier and the Roman Army struggled to stop them. In 270, the barbarian Juthungi and Vandals invaded northern Italy, inflicting a severe defeat on the Romans at Placentia (modern Piacenza) before eventually being driven back. Further trouble broke out in Rome itself in the summer of 271, when the mint workers rose in rebellion. Several thousand people died in the fierce fighting that resulted.

Aurelian's construction of the walls as an emergency measure was a reaction to the barbarian invasion of 270; the historian Aurelius Victor states explicitly that the project aimed to alleviate the city's vulnerability. It may also have been intended to send a political signal as a statement that Aurelian trusted that the people of Rome would remain loyal, as well as serving as a public declaration of the emperor's firm hold on power. The construction of the walls was by far the largest building project that had taken place in Rome for many decades, and their construction was a concrete statement of the continued strength of Rome.[3] The construction project was unusually left to the citizens themselves to complete as Aurelian could not afford to spare a single legionary for the project. The root of this unorthodox practice was due to the imminent barbarian threat coupled with the wavering strength of the military as a whole due to being subject to years of bloody civil war, famine and the Plague of Cyprian.

The walls were built in the short time of only five years, though Aurelian himself died before the completion of the project. Progress was accelerated, and money saved, by incorporating existing buildings into the structure. These included the Amphitheatrum Castrense, the Castra Praetoria, the Pyramid of Cestius, and even a section of the Aqua Claudia aqueduct near the Porta Maggiore. As much as a sixth of the walls is estimated to have been composed of pre-existing structures. An area behind the walls was cleared and sentry passages were built to enable it to be reinforced quickly in an emergency.

The actual effectiveness of the wall is disputable, given the relatively small size of the city's garrison. The entire combined strength of the Praetorian Guard, cohortes urbanae, and vigiles of Rome was only about 25,000 men – far too few to defend the circuit adequately. However, the military intention of the wall was not to withstand prolonged siege warfare; it was not common for the barbarian armies to besiege cities, as they were insufficiently equipped and provisioned for such a task. Instead, they carried out hit-and-run raids against ill-defended targets. The wall was a deterrent against such tactics.

Parts of the wall were doubled in height by Maxentius, who also improved the watch-towers. In 401, under Honorius, the walls and the gates were improved. At this time, the Tomb of Hadrian across the Tiber was incorporated as a fortress in the city defenses.

Gates

List of gates (porte), from the northernmost and clockwise:

• Porta del Popolo (Porta Flaminia) – here begins via Flaminia

• Porta Pinciana

• Porta Salaria – here begins via Salaria

• Porta Pia – here begins the new via Nomentana

• Porta Nomentana – here began the old via Nomentana

• Porta Praetoriana – old entrance to Castra Praetoria, the camp of the Praetorian Guard

• Porta Tiburtina – here begins via Tiburtina

• Porta Maggiore (Porta Praenestina) – here three aqueducts meet, and via Praenestina begins

• Porta San Giovanni – near Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano

• Porta Asinaria – here begins the old via Tuscolana

• Porta Metronia

• Porta Latina – here begins via Latina

• Porta San Sebastiano (Porta Appia) – here begins the Appian Way

• Porta Ardeatina

• Porta San Paolo (Porta Ostiense) – next to the Pyramid of Cestius, leading to Basilica di San Paolo fuori le Mura, here via Ostiense begins

Gates in Trastevere (from the southernmost and clockwise):

• Porta Portuensis

• Porta Aurelia Pancraziana

• Porta Settimiana

• Porta Aurelia-Sancti Petri

Inns

- Nigrum Unicornis -- (Inn of the Black Unicorn)

Law & Lawlessness

Monuments

See: List of ancient monuments in Rome -- Wikipedia

Amphitheaters

- Amphitheater of Caligula -- Built during the reign of the emperor Caligula. It was situated on the Campus Martius, probably near the Saepta Julia. (Location: Campus Martius) - {Demolished}

- Amphitheatrum Castrense -- This ancient Roman amphitheater of Rome is situated next to the church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme. (Location: Esquiline Hill)

- Colosseum of Rome -- Also known as the Flavian Amphitheatre it is the largest oval amphitheater built during the Roman Empire, it is located in the center of the city. (Location: Center of Rome)

- Amphitheater of Nero -- The Amphitheater of Nero was a wooden amphitheater built by the Roman emperor Nero around 64 CE. {Destroyed during the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD}

- Amphitheater of Statilius Taurus -- was an amphitheatre in ancient Rome. {Destroyed during the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD}

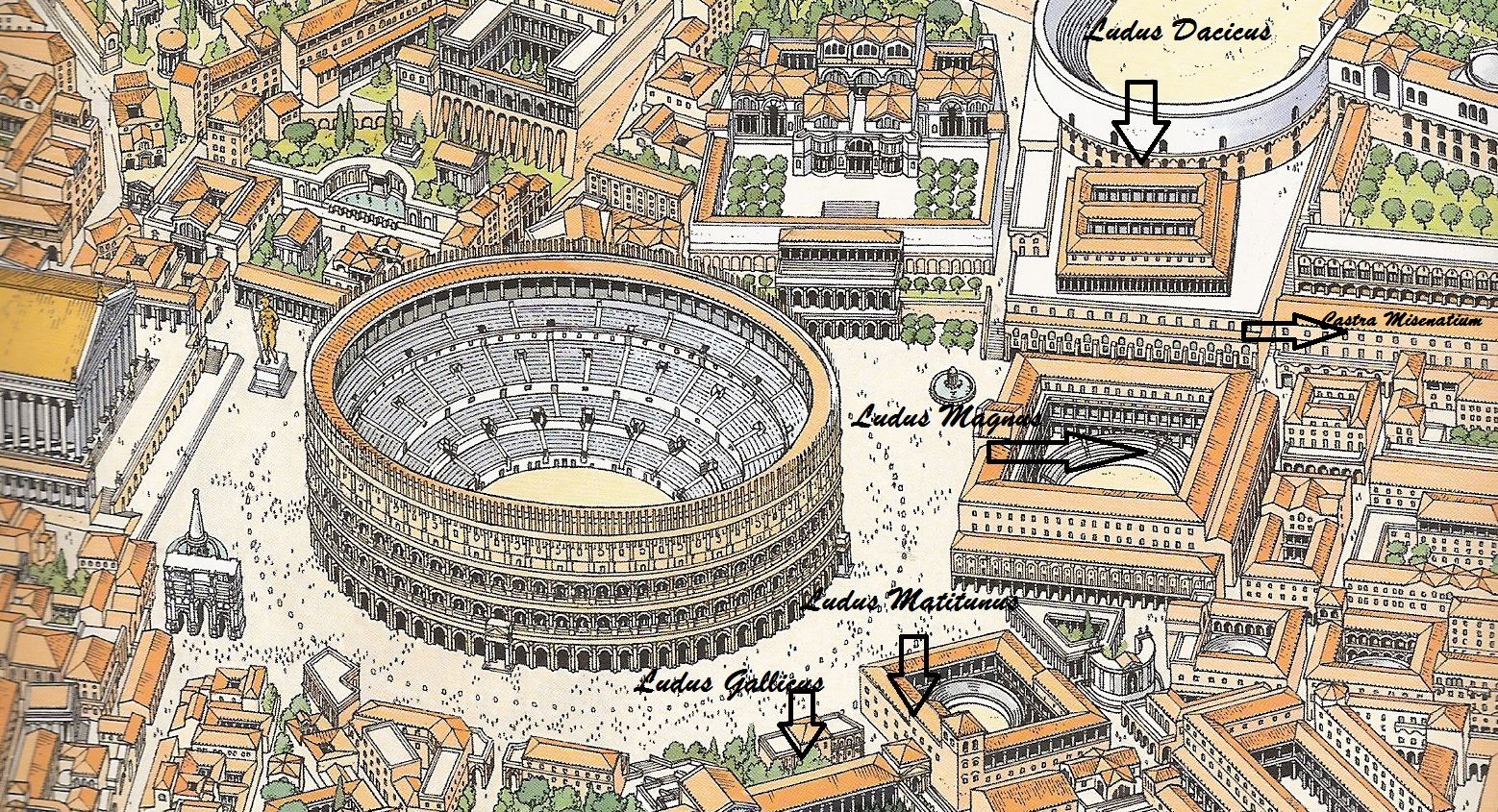

Ludus of Rome

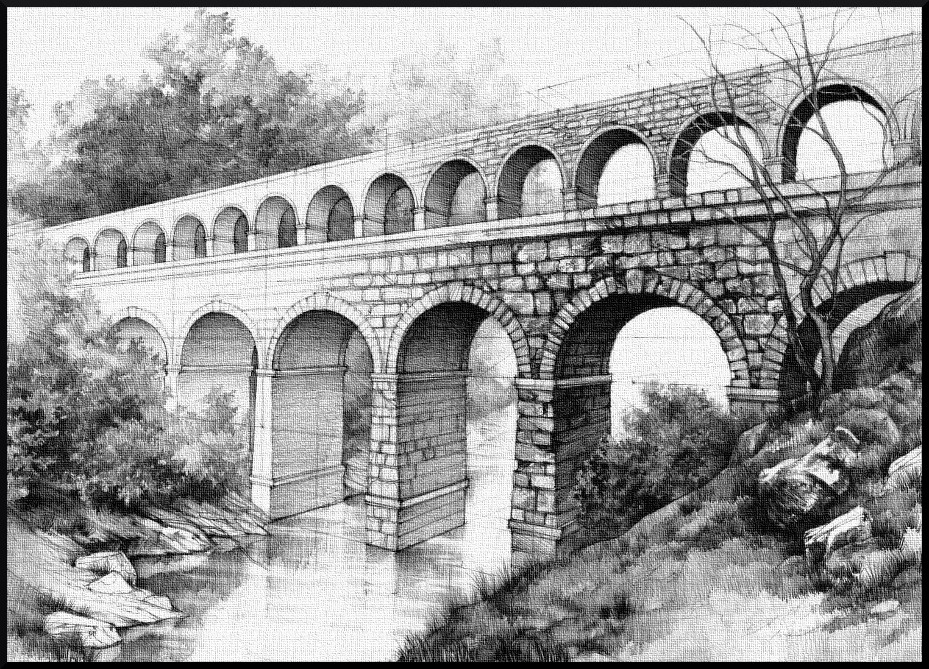

Aqueducts

- Anio Novus

- Anio Vetus

- Aqua Alexandriana

- Aqua Alsietina

- Aqua Appia

- Aqua Augusta (Rome)|Aqua Augusta

- Aqua Claudia

- Aqua Julia

- Aqua Marcia

- Aqua Martia

- Aqua Tepula

- Aqua Traiana

- Aqua Virgo

Arches (Triumphal)

- Arch of Constantine

- Arch of Septimius Severus

- Arcus Argentariorum

- Arcus Novus

- Arch of Arcadius, Honorius and Theodosius

- Arch of Augustus

- Arch of Claudius (British victory)

- Arches of Claudius

- Arch of Constantine

- Arch of Dolabella and Silanus

- Arch of Drusus

- Arches of Drusus and Germanicus

- Arch of Gallienus

- Arch of Gratian, Valentinian and Theodosius

- Arch of Janus

- Arch of Lentulus and Crispinus

- Arch of Nero

- Arch of Octavius

- Arch of Pietas

- Arch of Septimius Severus

- Arch of Tiberius

- Arch of Titus (Circus Maximus)

- Arch of Titus (Roman Forum)

Baths

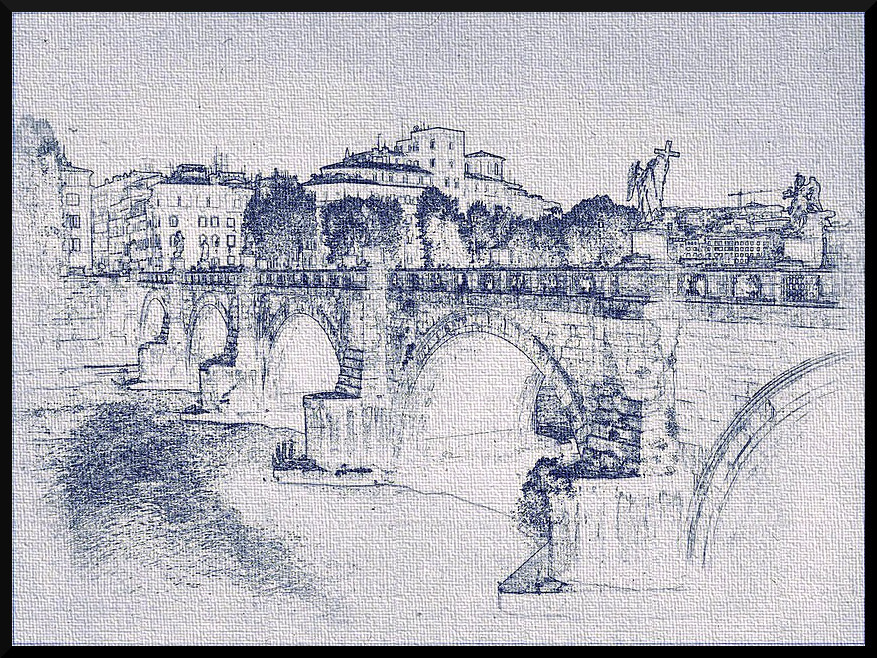

Bridges

- Ponte Sant'Angelo -- Ponte Sant'Angelo, once the Aelian Bridge or Pons Aelius, meaning the Bridge of Hadrian, is a Roman bridge completed in 134 AD by Roman Emperor Hadrian, to span the Tiber, from the city center to his newly constructed mausoleum, now the towering Castel Sant'Angelo. The bridge is faced with travertine marble and spans the Tiber with five arches, three of which are Roman; it was approached by means of ramp from the river.

- Pons Aemilius

- Pons Agrippae

- Pons Aurelius

- Pons Cestius

- Pons Fabricius

- Pons Milvius

- Pons Neronianus -- The Pons Neronianus or Bridge of Nero was an ancient bridge in Rome built during the reign of the emperors Caligula or Nero to connect the western part of the Campus Martius with the Campus Vaticanus ("Vatican Fields"), where the Imperial Family owned land along the Via Cornelia. The bridge is now referred to as the Pons ruptus ("broken bridge"), because it will remain broken throughout the Middle Ages.

- Pons Probi

- Pons Sublicius

Catacombs

Rome has a extensive number of ancient catacombs, or underground burial places beneath or near the city, of which there are at least forty. Though most famous for Christian burials, they include pagan and Jewish burials, either in separate catacombs or mixed together. The first large-scale catacombs were excavated from the 2nd century onwards, mainly as a response to overcrowding and shortage of land. Originally they were carved through tuff, a soft volcanic rock, outside the boundaries of the city, because Roman law forbade burial places within city limits.

Those Who Came Before

The Etruscans, like many other European people, used to bury their dead in underground chambers. The original Roman custom was cremation, after which the burnt remains were kept in a pot, ash-chest or urn, often in a columbarium. From about the 2nd century AD, inhumation (burial of unburnt remains) became more fashionable, in graves or sarcophagi, often elaborately carved, for those who could afford them. Christians also preferred burial to cremation because of their belief in bodily resurrection at the Second Coming.

Jews and Christians

Since most Christians and Jews at that time belonged to the lower classes or were slaves, they usually lacked the resources to buy land for burial purposes. Instead, networks of tunnels were dug in the deep layers of tuff which occurred naturally on the outskirts of Rome. At first, these tunnels were probably not used for regular worship, but simply for burial and, extending pre-existing Roman customs, for memorial services and celebrations of the anniversaries of Christian martyrs. There are sixty known subterranean burial chambers in Rome. They were built outside the walls along main Roman roads, like the Via Appia, the Via Ostiense, the Via Labicana, the Via Tiburtina, and the Via Nomentana. Names of the catacombs – like St Calixtus and St Sebastian, which is alongside Via Appia – refer to martyrs that may have been buried there. About 80% of the excavations used for Christian burials date to after the time of the persecutions.

Construction

Roman catacombs are made up of underground passages (ambulacra), out of whose walls graves (loculi) were dug. These loculi, generally laid out vertically (pilae), could contain one or more bodies. A loculus large enough to contain two bodies was referred to as a bisomus. Another type of burial, typical of Roman catacombs, was the arcosolium, consisting of a curved niche, enclosed under a carved horizontal marble slab. Cubicula (burial rooms containing loculi all for one family) and cryptae (chapels decorated with frescoes) are also commonly found in catacomb passages. When space began to run out, other graves were also dug in the floor of the corridors - these graves are called formae.

Excavators (fossors), built vast systems of galleries and passages on top of each other. They lie 7–19 metres (23–62 ft) below the surface in an area of more than 2.4 square kilometres (590 acres). Narrow steps that descend as many as four stories join the levels. Passages are about 2.5 by 1 metre (8.2 ft × 3.3 ft). Burial niches (loculi) were carved into walls. They are 40–60 centimetres (16–24 in) high and 120–150 centimetres (47–59 in) long. Bodies were placed in chambers in stone sarcophagi in their clothes and bound in linen. Then the chamber was sealed with a slab bearing the name, age and the day of death. The fresco decorations provide the main surviving evidence for Early Christian art, and initially show typically Roman styles used for decorating homes - with secular iconography adapted to a religious function. The catacomb of Saint Agnes is a small church. Some families were able to construct cubicula which would house various loculi and the architectural elements of the space would offer a support for decoration. Another excellent place for artistic programs were the arcosolia.

The Catacombs of Rome

The Roman catacombs, of which there are forty in the suburbs, were built along the consular roads out of Rome, such as the Appian way, the via Ostiense, the via Labicana, the via Tiburtina, and the via Nomentana.

- Catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter -- These catacombs are situated on the ancient Via Labicana, today Via Casilina, near the church of Santi Marcellino e Pietro ad Duas Lauros. Their name refers to the Christian martyrs Marcellinus and Peter who, according to tradition, were buried here, near the body of St. Tiburtius.

- Catacombs of Domitilla -- Close to the Catacombs of San Callisto are the large and impressive Catacombs of Domitilla (named after Saint Domitilla), spread over 17 kilometres (11 miles) of underground caves.

- Catacombs of Commodilla -- These catacombs, on the Via Ostiensis, contain one of the earliest images of a bearded Christ. They originally held the relics of Saints Felix and Adauctus.

- Catacombs of Generosa -- Located on the Campana Road, these catacombs are said to have been the resting place, perhaps temporarily, of Simplicius, Faustinus and Beatrix, Christian Martyrs who died in Rome during the Diocletian persecution (302 or 303).

- Catacombs of Praetextatus -- These are found along the via Appia, and were built at the end of 2nd century. They consist of a vast underground burial area, at first in pagan then in Christian use, housing various tombs of Christian martyrs. In the oldest parts of the complex may be found the "cubiculum of the coronation", with a rare depiction for that period of Christ being crowned with thorns, and a 4th-century painting of Susanna and the old men in the allegorical guise of a lamb and wolves.

- Catacombs of Priscilla -- The Catacomb of Priscilla, situated at the Via Salaria across from the Villa Ada, probably derives its name from the name of the landowner on whose land they were built. They are looked after by the Benedictine nuns of Priscilla.

- Catacombs of San Callisto -- Sited along the Appian way, these catacombs were built after AD 150, with some private Christian hypogea and a funeral area directly dependent on the Catholic Church. It takes its name from the deacon Saint Callixtus, proposed by Pope Zephyrinus in the administration of the same cemetery - on his accession as pope, he enlarged the complex, that quite soon became the official one for the Roman Church. The arcades, where more than fifty martyrs and sixteen pontiffs were buried, form part of a complex graveyard that occupies fifteen hectares and is almost 20 km (12 mi) long.

- Catacombs of San Lorenzo -- Built into the hill beside San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, these catacombs are said to have been the final resting place of St. Lawrence. The church was built by Pope Sixtus III and later remodeled into the present nave. Sixtus also redecorated the shrine in the catacomb and was buried there.

- Catacombs of San Pancrazio -- Established underneath the San Pacrazio basilica which was built by Pope Symmachus on the place where the body of the young martyr Saint Pancras, or Pancratius, had been buried. In the 17th century, it was given to the Discalced Carmelites, who completely remodeled it. The catacombs house fragments of sculpture and pagan and early Christian inscriptions.

- Catacombs of San Sebastiano -- One of the smallest Christian cemeteries, this has always been one of the most accessible catacombs and is thus one of the least preserved (of the four original floors, the first is almost completely gone).

- Catacombs of San Valentino -- These catacombs were dedicated to Saint Valentine. In the 13th century, the martyr's relics were transferred to Basilica of Saint Praxedes.

- Catacombs of Sant'Agnese -- Built for the conservation and veneration of the remains of Saint Agnes of Rome. Agnes' bones are now conserved in the church of Sant'Agnese fuori le mura in Rome, built over the catacomb. Her skull is preserved in a side chapel in the church of Sant'Agnese in Agone in Rome's Piazza Navona.

- Catacombs of via Anapo -- On the via Salaria, the Catacombs of via Anapo are datable to the end of the 3rd or the beginning of the 4th century, and contain diverse frescoes of biblical subjects.

- Jewish Catacombs -- There are six known Jewish catacombs in Rome, two of which are open to the public: Vigna Randanini and Villa Torlonia.

Cemeteries

- Columbarium of Pomponius Hylas -- is a 1st-century AD Roman columbarium, situated near the Porta Latina on the Via Appia. Columbarium

- Esquiline Necropolis -- The Esquiline Necropolis was a prehistoric necropolis on the Esquiline in Rome, in use until the end of the 1st century AD.

- Vatican Necropolis -- The Vatican Necropolis lies under the Vatican City, at depths varying between 5–12 meters below Saint Peter's Basilica.

Churches

The Vatican

- Old St.Peter's Basilica -- Old St. Peter's Basilica was the building that stood, from the 4th to 16th centuries, where the new St. Peter's Basilica stands today in Vatican City.

Titular Churches

In the Catholic Church, a prelate raised to the rank of Cardinal Priest or Cardinal Deacon is assigned title to a church in Rome, that is, his titular church, which establishes his relationship to the Diocese of Rome, which has the pope for its bishop.

- Basilica Sanctae Mariae de Ara coeli in Capitolium -- The Basilica of St. Mary of the Altar of Heaven is a titular basilica in Rome, located on the highest summit of the Campidoglio.

- Santa Croce in Gerusalemme -- The Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem or Basilica di Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, is a minor basilica and titular church in Esquilino. It is one of the Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome.

See: List of titular churches in Rome -- Wikipedia

Other Churches

- Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore -- is a Papal major basilica and the largest Catholic Marian church in Rome

- Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls -- is one of Rome's four ancient, Papal, major basilicas.

- Santa Maria in Trastevere -- is a titular minor basilica in the Trastevere district, and one of the oldest churches of Rome.

- Santi Quattro Coronati -- is an ancient basilica in Rome, Italy. The church dates back to the 4th (or 5th) century, and is devoted to four anonymous saints and martyrs.

- Basilica of Saint Praxedes -- commonly known in Italian as Santa Prassede, is an ancient titular church and minor basilica in Rome, Italy, located near the papal basilica of Saint Mary Major.

Circuses

Columns

- Trajan's Column

- Column of Antoninus Pius

- Column of Marcus Aurelius

- Column of Phocas

Convents

Fountains

Gardens

Mausolea

- Hadrian's Mausoleum

- Mausoleum of Augustus

- Mausoleum of Helena

- Mausoleum of Maxentius

Porticoes

Statues

- Colossus of Constantine

- Colossus of Nero

- Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius

Tombs

- Casal Rotondo

- Pyramid of Cestius

- Tomb of Caecilia Metella

- Tomb of Eurysaces the Baker

- Tomb of Geta

- Tomb of the Scipios

Regiones de Roma

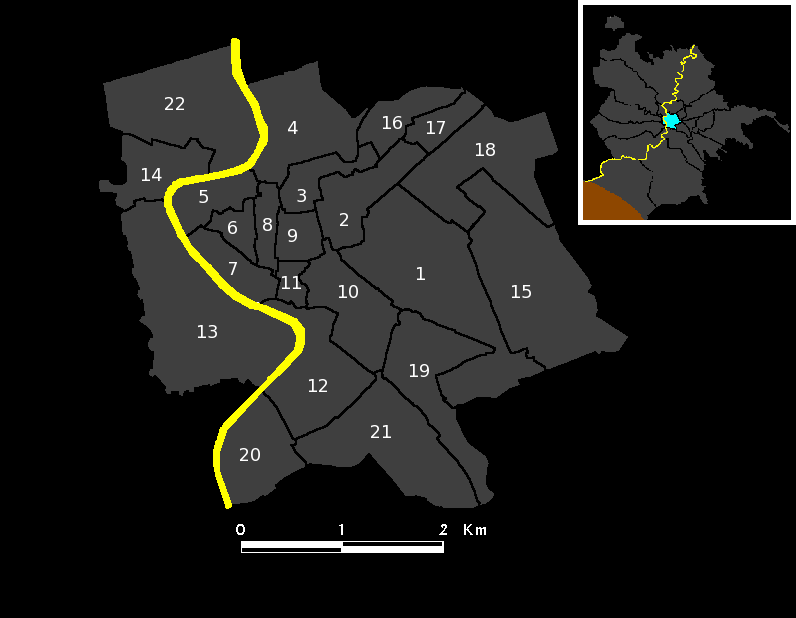

During the Middle Ages, Rome was divided into a number of administrative regions (Latin, regiones), usually numbering between twelve and fourteen, which changed over time.

Evolution of the Regions

Originally the city of Rome had been divided by Augustus into 14 regions in 7 BC. Then sometime during the 4th century, Christian authorities instituted seven ecclesiastical regions, which ran parallel to the civil regions. With the collapse of Imperial authority in the Western Roman Empire, after the death of Julius Nepos in 480, much of the old imperial administrative structures began to fall into abeyance.

After the destructive Gothic Wars of the 6th century, the city of Rome had become virtually depopulated. When the city began to recover it was inhabited in new parts and whole districts were in ruins. Consequently, the Augustan regions now had no relationship to the administration of the city, but they continued to be used as a means for identifying property. But as Rome slowly recovered from the disasters of the Gothic wars it became necessary to organize the city for the purpose of defense, and one theory contends that this was the origin of the twelve medieval regions. In particular, it is suggested that it was connected with the Byzantine military system (the scholae militiae) and was introduced into Rome in the 7th century, along with its implementation at Ravenna. This saw the creation of a new series of regions based upon a different principle from either of the older ones. However, this revision did not last much longer than two centuries after the fall of the Exarchate of Ravenna in 751.

Certainly, the division of the city according to the revised civil and ecclesiastical regions appears to have fallen out of use in the confusion of the 10th century. Local variations seem to have sprung up that were adopted, used and then discarded as the years progressed. It has been conjectured that the sack of Rome by Robert Guiscard in 1084 caused a displacement of the population which probably made a revision of the regions necessary. The district from the Lateran Palace to the Colosseum was engulfed and ruined by fire, and the Caelian and Aventine hills were gradually abandoned. The number of regions needed for the south and south-east of the city became smaller, while there emerged a greater need for the organization of the rapidly growing districts to the north-west and along the Tiber.

The next major reform was after the revolution of 1143 and the establishment of the Commune of Rome, as the city was redivided into 14 regions. There was a minor adjustment made in the 13th century, bringing the total number down to thirteen, and it wasn’t until 1586 that another region was created, once again bringing the total number up to fourteen, and Rome kept these administrative divisions intact until the 19th century.

The Regiones of Rome

Unlike the Augustan regions of Rome, the medieval regions were not numbered, and few had any relationship to the ancient Roman divisions. They are numbered here merely for convenience.

- Medieval Rioni

-

- Monti - I

- Trevi - II

- Colonna - III

- Campo Marzio - IV

- Ponte - V

- Parione - VI

- Regola - VII

- Sant Eustachio - VIII

- Pigna - IX

- Campitelli - X

- Sant Angelo - XI

- Ripa - XII

- Trastevere - XIII

- Civitas Leonina - The Vatican

- Ostia Antica & Gregoriopolis - Rome's ancient Mediterranean port, now useless as the river Tiber has shifted leaving Ostia landlocked.

http://roma.andreapollett.com/S5/rioni.htm

Private Residences

- -- Lateran Palace -- The Lateran Palace (Latin: Palatium Lateranense), formally the Apostolic Palace of the Lateran (Latin: Palatium Apostolicum Lateranense), is an ancient palace of the Roman Empire and later the main papal residence in southeast Rome.

- -- Quadrilaterae Palace -- Ancient residence of Rome's undead Augustus, Constantius.

Taverns

Religion

Roman Catholic Church of Rome

Churches

- Church of San Pancrazio -- Located west of the city, beyond the Aurelian Wall outside of the Trantiberum.

Cults

Pagan Temples

Aventine Hill

- Temple of Bona Dea

- Temple of Ceres

- Temple of Diana Aventina

- Temple of Juno Regina

- Temple of Luna

- Temple of Minerva

Caelian Hill

- Temple of Claudius

Capitoline Hill

- Temple of Fides

- Temple of Jupiter Custos

- Temple of Jupiter Feretrius

- Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

- Temple of Jupiter Tonans

- Temple of Juno Moneta

- Temple of Ops

- Temple of Veiovis

- Temple of Fortuna Redux

Campus Martius

- Pantheon

- Temple of Apollo Sosianus

- Temple of Bellona

- Temple of Castor and Pollux

- Temple of Diana (Rome)

- Temple of the Dii Inferi

- Temple of Feronia

- Temple of Fortuna Equestris

- Temple of Hadrian

- Temple of Hercules Custos

- Temple of Hercules Musarum

- Temple of Isis and Serapis

- Temple of Juno Regina

- Temple of Jupiter Stator

- Temple of Juturna

- Temple of the Lares

- Temple of Matidia

- Temple of the Sun

- Temple of Mars

- Temple of Minerva Chalcidica

- Temple of Neptunus

- Temple of Fortuna Huiusce Diei

- Temple of the Nymphs

- Temple of Vulcanus

Esquiline Hill

- Temple of Juno Lucina

- Temple of Minerva Medica (no longer extant)

- Nymphaeum called the 'Temple of Minerva Medica'

Forum Boarium

- Temple of Hercules Pompeianus

- Temple of Hercules Victor

- Temple of Fortuna

- Temple of Mater Matuta

- Temple of Portunus

- Temple of Pudicitia Patricia

Forum Holitorium

- Temple of Janus

- Temple of Juno Sospita

- Temple of Piety

- Temple of Spes

- Temple of Victoria

Forum Romanum

Imperial fora

- Temple of Mars Ultor

- Temple of Minerva

- Temple of Trajan

- Temple of Peace

- Temple of Venus Genetrix

Palatine Hill

- Elagabalium

- Temple of Apollo Palatinus

- Temple of Cybele

- Temple of Juno Sospita

- Temple of Victory

- Temple of Fortuna Respiciens

Quirinal Hill

- Temple of the Flavia gens

- Temple of Quirinus

- Temple of Serapis

Tiber Island

- Temple of Asclepius

- Temple of Faunus

Werewolf Septs

While there are many ancient and abandoned temples in Rome, not all are abandoned. Of the Septs of the Garou, until recently there were none. Now there are two, the Sept of the Scroll Bearers awakened by the Warders of Man and the Sept of the Capitoline Wolf awakened by the tribe of Shadow Lords.

Nearby Septs

Visitors

Whore Houses

Nocturna Animalia

Rome at the close of the 11th century is dangerously crowded by Cainite standards. There are over thirty immortals who are considered "citizens". Unfortunately, if one includes all the vampiric visitors and dignitaries, not to mention the scum and riffraff that lurk on the edges of the respectable nocturnal society of Rome, there may be twice that number. This situation is new to the Eternal City and represents an ever present and growing threat to the Children of Caine, for every night the Silence of the Blood is imperiled.

Et Atrium Romanus (Court of Rome)

- Constantius -- Caesar ex Obumbratio

Romanus Senatus (Roman Senators)

- Achard de Hauteville -- Ventrue Senator {Junior}

- Artemisia -- Brujah Senator

- Giuseppe Giovanni -- Cappadocian Senator

- Gracis Nostinus -- Ventrue Senator {Senior}

- Hadrianus -- Lasombra Senator

- Lino Agnellini -- Toreador Senator

Nobilibus familiis Romanorum (High Clans)

Inferiore gens ab Roma (Low Clans)

Memoria pro Mortuis (Remembrances for the Dead)

- Collat -- First Prince of Rome, who officially abdicated in favor of his youngest childe Titus Venturus Camillus otherwise known as Camilla. Supposedly, he departed Rome in the last decades before the First Punic War.

- Camilla -- The Second Prince of Rome during the transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire — a period of time that includes the Punic Wars that destroyed Carthage. He vanished during the Great Fire that devastated Rome in 64 CE, and was presumed to have met his Final Death in the blaze.

- Marius Maior -- Fallen Patriarch -- Slain by his childe Hrothulf, he was the last of true Roman member of the line of Camilla.

- Massimiliano Nicotera -- The second of two childer Embraced by Petronius the Arbiter before his immigration to Constantinople. He and all his childer died in the fire set by the Normans in the Riots of 1084.

Incognitos (Strangers and Aliens)

- Cassius -- Lord of the Catacombs {Rumored}

- Fabrizio Ulfila -- Ashen priest of Rome.

- Sybil -- Queen of Darkness

- The Sculptor -- Priest of Persephone

- Thaddeus -- The Penitent Pagan

- Trajan -- Exploratorem dominum

Wraiths of Rome

- Orsina -- A young girl of station who died of plague {servant of Lady Mortis}.

- Hekate ex Duplicata

Storytelling Medieval Rome

Mood of Medieval Rome: Darkness / Hunger / Secrecy

Theme:

The Roman Cainite Carnival: At Caesar Constantius' pleasure or in times of civil war, the prince can call for the Roman Carnival. Essentially, a period of Elysium, it serves as a time during which vendettas and feuds can lapse after a flair up. It is also called if some distinguished visitor arrives in the Eternal city. It bears more than a passing semblance to the Elysium of the Roman era, save that it lasts for a period of nights or weeks and only covers certain specified sites. Constantius can revoke the Roman carnival at will, but has rarely done so. It is one of the city's most stable and venerated traditions and has contributed to the survival of the nocturnal society of Roman Cainites.

Stories of the Eternal City

- Quinquennium in statum sacrificium noctibus

- Quae Infra - (What lies beneath)

- Epicinium - (The Aftermath)

- Et pestem serenitatem - (The Plague of Serenity)

Websites