Paris - La Belle Époque: Difference between revisions

| Line 539: | Line 539: | ||

===Tremere=== | ===Tremere=== | ||

* -- [[Lazare Monet]] -- Creator of [[La Transsubstantiation de la Cuisine]]. | |||

---- | ---- | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 20:48, 7 March 2017

- Past Imperfect -PLBE- Paris - 1933 -PLBE- Paris

Quote

In Paris, everybody wants to be an actor; nobody is content to be a spectator. -- Jean Cocteau

La Belle Époque: An Introduction

The Belle Époque or La Belle Époque (French pronunciation: [bɛlepɔk]; French for "Beautiful Era") was a period of Western European history. It is conventionally dated from the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 to the outbreak of World War I in around 1914. Occurring during the era of the French Third Republic (beginning 1870), it was a period characterized by optimism, regional peace, economic prosperity and technological, scientific and cultural innovations. In the climate of the period, especially in Paris, the arts flourished. Many masterpieces of literature, music, theater, and visual art gained recognition. The Belle Époque was named, in retrospect, when it began to be considered a "Golden Age" in contrast to the horrors of World War I.

In the United Kingdom, the Belle Époque overlapped with the late Victorian era and the Edwardian era. In Germany, the Belle Époque coincided with the Wilhelminism; in Russia with the reigns of Alexander III and Nicholas II. In the newly-rich United States, emerging from the Panic of 1873, the comparable epoch was dubbed the "Gilded Age". In Brazil it started with the end of the Paraguayan War, and in Mexico the period was known as the "Porfiriato".

Popular Culture & Fashions

The French publics nostalgia for the Belle Époque period was based largely on the peace and prosperity connected with it in retrospect. Two devastating world wars and their aftermath made the Belle Époque appear to be a time of joie de vivre (joy of living) in contrast to 20th century hardships. It was also a period of stability that France enjoyed after the tumult of the early years of the French Third Republic, beginning with France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, the Paris Commune, and the fall of General Georges Ernest Boulanger. The defeat of Boulanger, and the celebrations tied to the 1889 World's Fair in Paris, launched an era of optimism and affluence. French imperialism was in its prime. It was a cultural center of global influence, and its educational, scientific and medical institutions were at the leading edge of Europe.

It was not entirely the reality of life in Paris or in France, however. France had a large economic underclass who never experienced much of the Belle Époque's wonders and entertainments. Poverty remained endemic in Paris's urban slums and rural peasantry for decades after the Belle Époque ended. The Dreyfus Affair exposed the dark realities of French anti-Semitism and government corruption. Conflicts between the government and the Roman Catholic Church were regular during the period. Some of the artistic elite saw the Fin de siècle in a pessimistic light. Grand foyer of the Folies Bergère cabaret.

Those who were able to benefit from the prosperity of the era were drawn towards new forms of light entertainment during the Belle Époque, and the Parisian bourgeoisie, or the successful industrialists called nouveau-riches, became increasingly influenced by the habits and fads of the city's elite social class, known popularly as Tout-Paris ("all of Paris", or "everyone in Paris"). The Casino de Paris opened in 1890. For Paris's less affluent public, entertainment was provided by cabarets, bistros and music halls.

The Moulin Rouge cabaret is a Paris landmark still open for business today. The Folies Bergère was another landmark venue. Burlesque performance styles were more mainstream in Belle Époque Paris than in more staid cities of Europe and America. Liane de Pougy, dancer, socialite and courtesan, was well known in Paris as a headline performer at top cabarets. Belle Époque dancers such as La Goulue and Jane Avril were Paris celebrities, who modeled for Toulouse-Lautrec's iconic poster art. The Can-can dance was a popular 19th-century cabaret style that appears in Toulouse-Lautrec's posters from the era.

The Eiffel Tower, built to serve as the grand entrance to the 1889 World's Fair held in Paris, became the accustomed symbol of the city, to its inhabitants and to visitors from around the world. Paris hosted another successful World's Fair in 1900, the Exposition Universelle (1900). Paris had been profoundly changed by the French Second Empire reforms to the city's architecture and public amenities. Haussmann's renovation of Paris changed its housing, street layouts, and green spaces. The walkable neighborhoods were well-established by the Belle Époque.

Cheap coal and cheap labor contributed to the cult of the orchid and made possible the perfection of fruits grown under glass, as the apparatus of state dinners extended to the upper classes. Exotic feathers and furs were more prominently featured in fashion than ever before, as "haute couture" was invented in Paris, the center of the Belle Époque, where fashion began to move in a yearly cycle. In Paris, restaurants such as Maxim's Paris achieved a new splendor and cachet as places for the rich to parade. Maxim's Paris was arguably the city's most exclusive restaurant. Bohemian lifestyles gained a different glamor, pursued in the cabarets of Montmartre.

French cuisine continued to climb in the esteem of European gourmets during the Belle Époque. The word "ritzy" was invented during this era, referring to the posh atmosphere and clientèle of the Hôtel Ritz Paris. The head chef and co-owner of the Ritz, Auguste Escoffier, was the pre-eminent French chef during the Belle Époque. Escoffier modernized French "haute cuisine", also doing much work to spread its reputation abroad with business projects in London in addition to Paris. Champagne was perfected during the Belle Époque. The alcoholic spirit absinthe was cited by many Art Nouveau artists as a muse and inspiration and can be seen in much of the artwork of the time.

Large public buildings such as the Opéra Garnier devoted enormous spaces to interior designs as Art Nouveau show places. After the mid-19th century, railways linked all the major cities of Europe to spa towns like Biarritz, Deauville, Vichy, Arcachon and the French Riviera. Their carriages were rigorously divided into first-class and second-class, but the super-rich now began to commission private railway coaches, as exclusivity as well as display was a hallmark of opulent luxury.

Politics of the Age

The years between the Franco-Prussian War and World War I were characterized by unusual political stability in western and central Europe. Although tensions between the French and German governments persisted as a result of the French loss of Alsace-Lorraine to Germany in 1871, diplomatic conferences, including the Congress of Berlin in 1878, the Berlin Congo Conference in 1884, and the Algeciras Conference in 1906, mediated disputes that threatened the general European peace. Indeed, for many Europeans in the Belle Époque period, transnational, class-based affiliations were as important as national identities, particularly among aristocrats. An upper-class gentleman could travel through much of Western Europe without a passport and even reside abroad with minimal bureaucratic regulation. World War I, mass transportation, the spread of literacy, and various citizenship concerns changed this.

The Belle Époque featured a class structure that ensured cheap labor. The Paris Metro underground railway system joined the omnibus and streetcar in transporting the working population, including those servants who did not live in the wealthy centers of cities. One result of this commuting was suburbanization allowing working-class and upper-class neighborhoods to be separated by large distances.

Meanwhile, the international workers' movement also reorganized itself and reinforced pan-European, class-based identities among the classes whose labor supported the Belle Époque. The most notable transnational socialist organization was the Second International. Anarchists of different affiliations were active during the period leading up to World War I. Political assassinations and assassination attempts were still rare in France (unlike in Russia) but there were some notable exceptions, including President Marie François Sadi Carnot in 1894. A bomb was detonated in the Chamber of Deputies of France in 1893, causing injuries but no deaths. Terrorism against civilians occurred in 1894, perpetrated by Émile Henry, who killed a cafe patron and wounded several others.

France enjoyed relative political stability at home during the Belle Époque. The sudden death of President Félix Faure while in office took the country by surprise, but had no destabilizing effect on the government. The most serious political issue to face the country during this period was the Dreyfus Affair. Captain Alfred Dreyfus was wrongly convicted of treason, with fabricated evidence from French government officials. Anti-Semitism directed at Dreyfus, and tolerated by the general French public in everyday society, was a central issue in the controversy and the court trials that followed. Public debate surrounding the Dreyfus Affair grew to an uproar after the publication of J'accuse, a letter sent to newspapers by prominent novelist Émile Zola, condemning government corruption and French anti-Semitism. The Dreyfus Affair consumed the interest of the French for several years and it received heavy newspaper coverage.

European politics saw very few regime changes, the major exception being Portugal, which experienced a republican revolution in 1910. However, tensions between working-class socialist parties, bourgeois liberal parties, and landed or aristocratic conservative parties did increase in many countries, and it has been claimed that profound political instability belied the calm surface of European politics in the era. In fact, militarism and international tensions grew considerably between 1897 and 1914, and the immediate prewar years were marked by a general armaments competition in Europe. Additionally, this era was one of massive overseas colonialism, known as the "New Imperialism". The most famous portion of this imperial expansion was the Scramble for Africa.

Science & Technology

The Belle Époque was an era of great scientific and technological advancement in Europe and the world in general. Inventions of the Second Industrial Revolution that became generally common in this era include the perfection of lightly sprung, noiseless carriages in a multitude of new fashionable forms, which were superseded towards the end of the era by the automobile, which was for its first decade a luxurious experiment for the well-heeled. French automobile manufacturers such as Peugeot were already pioneers in automobile manufacturing. Edouard Michelin invented removable pneumatic tires for bicycles and automobiles in the 1890s. The scooter and moped are also Belle Époque inventions.

A number of French inventors patented products with a lasting impact on modern society. After the telephone joined the telegraph as a vehicle for rapid communication, French inventor Édouard Belin developed the Belinograph, or Wirephoto, to transmit photos by telephone. The electric light began to supersede gas lighting, and neon lights were invented in France.

France was a leader of early cinema technology. The cinématographe was invented in France by Léon Bouly and put to use by Auguste and Louis Lumière, brothers who held the first film screenings in the world. The Lumière brothers made many other innovations in cinematography. It was during this era that the motion pictures were developed, though these did not become common until after World War I.

Although the airplane remained a fascinating experiment, France was a leader in aviation. France established the world's first national air force in 1910. Two French inventors, Louis Breguet and Paul Cornu, made independent experiments with the first flying helicopters in 1907.

Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity in 1896 while working with phosphorescent materials. His work confirmed and explained earlier observations regarding uranium salts by Abel Niépce de Saint-Victor in 1857.

It was during this era that biologists and physicians finally came to understand the germ theory of disease, and the field of bacteriology was established. Louis Pasteur was perhaps the most famous scientist in France during this time. Pasteur developed pasteurization and a rabies vaccine. Mathematician and physicist Henri Poincaré made important contributions to pure and applied mathematics, and also published books for the general public on mathematical and scientific subjects. Marie Skłodowska-Curie worked in France, winning the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1903, and the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1911. Physicist Gabriel Lippmann invented integral imaging, still in use today.

Art & Literature

n 1890, Vincent van Gogh died. It was during the 1890s that his paintings achieved the admiration that had eluded them during Van Gogh's life, first among other artists, then gradually among the public. Reactions against the ideals of the Impressionists characterized visual arts in Paris during the Belle Époque. Among the post-Impressionist movements in Paris were the Nabis, the Salon de la Rose + Croix, the Symbolist movement (also in poetry, music, and visual art), Fauvism, and early Modernism. Between 1900 and 1914, Expressionism took hold of many artists in Paris and Vienna. Early works of Cubism and Abstraction were exhibited. Foreign influences were being strongly felt in Paris as well. The official art school in Paris, the École des Beaux-Arts, held an exhibition of Japanese printmaking that changed approaches to graphic design, particular posters and book illustration (Aubrey Beardsley was influenced by a similar exhibit when he visited Paris during the 1890s). Exhibits of African tribal art also captured the imagination of Parisian artists at the turn of the 20th century.

Art Nouveau is the most popularly recognized art movement to emerge from the period. This largely decorative style (Jugendstil in central Europe), characterized by its curvilinear forms, and nature inspired motifs became prominent from the mid-1890s and dominated progressive design throughout much of Europe. Its use in public art in Paris, such as Hector Guimard's Paris Métro stations, has made it synonymous with the city.

Prominent artists in Paris during the Belle Époque included post-Impressionists such as Odilon Redon, Gustave Moreau, Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Émile Bernard, Henri Rousseau, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (whose reputation improved substantially after his death), Giuseppe Amisani and a young Pablo Picasso. More modern forms in sculpture also began to dominate as in the works of paris-native Auguste Rodin.

Although Impressionism in painting began well before the Belle Époque, it had initially been met with skepticism if not outright scorn by a public accustomed to the realist and representational art approved by the Academy. In 1890, Monet started his series Haystacks. Impressionism, which had been considered the artistic avant-garde in the 1860s, did not gain widespread acceptance until after World War I. The academic painting style, associated with the Academy of Art in Paris, remained the most respected style among the public in Paris. Artists who appealed to the Belle Époque public include William-Adolphe Bouguereau, the English pre-Raphaelite John William Waterhouse, and Lord Leighton and his depictions of idyllic Roman scenes. More progressive tastes patronized the Barbizon school plein-air painters. These painters were associates of the Pre-Raphaelites, who inspired a generation of esthetic-minded "Souls".

Many successful examples of Art Nouveau, with notable regional variations, were built in France, Germany, Belgium, Spain, Austria (the Vienna Secession), Hungary, Bohemia and Latvia. It soon spread around the world, including to Brazil, Argentina, Mexico and the United States.

European literature underwent a major transformation during the Belle Époque. Literary realism and naturalism achieved new heights. Among the most famous French realist or naturalist authors are Guy de Maupassant and Émile Zola. Realism gradually developed into modernism, which emerged in the 1890s and came to dominate European literature during the Belle Époque's final years and throughout the inter-war years. The Modernist classic "In Search of Lost Time" was begun by Marcel Proust in 1909, to be published after World War I. The works of German Thomas Mann had a huge impact in France as well, such as "Death in Venice", published in 1912. Colette shocked France with the publication of the sexually frank Claudine novel series, and other works. Joris-Karl Huysmans, who came to prominence in the mid-1880s, continued experimenting with themes and styles that would be associated with Symbolism and the Decadent movement, mostly in his book à rebours. André Gide, Anatole France, Alain-Fournier, Paul Bourget are among France's most popular fiction writers of the era.

Among poets, the Symbolists such as Charles Baudelaire remained at the forefront. Although Baudelaire's poetry collection "Les Fleurs du mal" had been published in the 1850s, it exerted a strong influence on the next generation of poets and artists. The Decadent movement fascinated Parisians, intrigued by Paul Verlaine and above all Arthur Rimbaud, who became the archetypal enfant terrible of France. Rimbaud's Illuminations was published in 1886, and subsequently his other works were also published, influencing Surrealists and Modernists during the Belle Époque and after. Rimbaud's poems were the first works of free verse seen by the French public. Free verse and typographic experimentation also emerged in Un Coup de Dés Jamais N'Abolira Le Hasard by Stéphane Mallarmé, anticipating Dada and concrete poetry. Guillaume Apollinaire's poetry introduced themes and imagery from modern life to readers. Cosmopolis: A Literary Review had a far-reaching impact on European writers, and ran editions in London, Paris, Saint Petersburg, and Berlin.

Paris's popular bourgeois theater was dominated by the light farces of Georges Feydeau and cabaret performances. Theater adopted new modern methods, including Expressionism, and many playwrights wrote plays that shocked contemporary audiences either with their frank depictions of everyday life and sexuality or with unusual artistic elements. Cabaret theater also became popular.

Musically, the Belle Époque was characterized by salon music. This was not considered serious music but, rather, short pieces considered accessible to a general audience. In addition to works for piano solo or violin and piano, the Belle Époque was famous for its large repertory of songs (mélodies, romanze, etc.). The Italians were the greatest proponents of this type of song, its greatest champion being Francesco Paolo Tosti. Though Tosti's songs never completely left the repertoire, salon music generally fell into a period of obscurity. Even as encores, singers were afraid to sing them at serious recitals. In that period, waltzes also flourished. Operettas were also at the peak of their popularity, with composers such as Johann Strauss III, Emmerich Kálmán, and Franz Lehár. Many Belle Époque composers working in Paris are still popular today: Igor Stravinsky, Erik Satie, Claude Debussy, Lili Boulanger, Jules Massenet, César Franck, Camille Saint-Saëns, Gabriel Fauré and his pupil, Maurice Ravel.

Modern dance began to emerge as a powerful artistic development in theatre. Dancer Loie Fuller appeared at popular venues such as the Folies Bergère, and took her eclectic performance style abroad as well. Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes brought fame to Vaslav Nijinsky and established modern ballet technique. The Ballets Russes launched several ballet masterpieces, including The Firebird and The Rite of Spring (sometimes causing audience riots at the same time).

Appearance

[[]]

City Device

Climate

Paris has a typical Western European oceanic climate which is affected by the North Atlantic Current. The overall climate throughout the year is mild and moderately wet. Summer days are usually moderately warm and pleasant with average temperatures hovering between 15 and 25 °C (59 and 77 °F), and a fair amount of sunshine. Each year, however, there are a few days where the temperature rises above 30 °C (86 °F). Some years have even witnessed some long periods of harsh summer weather, such as the heat wave of 2003 where temperatures exceeded 30 °C (86 °F) for weeks, surged up to 39 °C (102 °F) on some days and seldom cooled down at night. More recently, the average temperature for July 2011 was 17.6 °C (63.7 °F), with an average minimum temperature of 12.9 °C (55.2 °F) and an average maximum temperature of 23.7 °C (74.7 °F).

Spring and autumn have, on average, mild days and fresh nights, but are changing and unstable. Surprisingly warm or cool weather occurs frequently in both seasons. In winter, sunshine is scarce; days are cold but generally above freezing with temperatures around 7 °C (45 °F). Light night frosts are however quite common, but the temperature will dip below −5 °C (23 °F) for only a few days a year. Snowfall is uncommon, but the city sometimes sees light snow or flurries with or without accumulation.

Rain falls throughout the year. Average annual precipitation is 652 mm (25.7 in) with light rainfall fairly distributed throughout the year. The highest recorded temperature is 40.4 °C (104.7 °F) on July 28, 1948, and the lowest is a −23.9 °C (−11.0 °F) on December 10, 1879.

Demonym

Parisian

Economy

Geography

Paris is located in northern central France. By road it is 450 kilometres (280 mi) south-east of London, 287 kilometres (178 mi) south of Calais, 305 kilometres (190 mi) south-west of Brussels, 774 kilometres (481 mi) north of Marseilles, 385 kilometres (239 mi) north-east of Nantes, and 135 kilometres (84 mi) south-east of Rouen. Paris is located in the north-bending arc of the river Seine, spread widely on both banks of the river, and includes two inhabited islands, the Île Saint-Louis and the larger Île de la Cité, which forms the oldest part of the city. The river’s mouth on the English Channel (La Manche) is about 233 mi (375 km) downstream of the city. Overall, the city is relatively flat, and the lowest point is 35 m (115 ft) above sea level. Paris has several prominent hills, of which the highest is Montmartre at 130 m (427 ft). Montmartre gained its name from the martyrdom of Saint Denis, first bishop of Paris atop the "Mons Martyrum" (Martyr's mound) in 250 A.D.

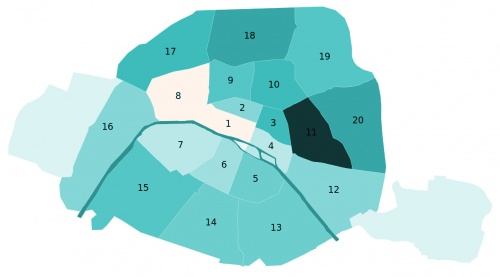

Excluding the outlying parks of Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes, Paris occupies an oval measuring about 87 km2 (34 sq mi) in area, enclosed by the 35 km (22 mi) ring road, the Boulevard Périphérique. The city's last major annexation of outlying territories in 1860 not only gave it its modern form but also created the twenty clockwise-spiralling arrondissements (municipal boroughs). From the 1860 area of 78 km2 (30 sq mi), the city limits were expanded marginally to 86.9 km2 (33.6 sq mi) in the 1920s. In 1929, the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes forest parks were officially annexed to the city, bringing its area to about 105 km2 (41 sq mi). The metropolitan area of the city is 2,300 km2 (890 sq mi).

Arrondissements

Introduction

The city of Paris is divided into twenty arrondissements municipaux, administrative districts, more simply referred to as arrondissements. These are not to be confused with departmental arrondissements, which subdivide the 101 French départements. The word "arrondissement", when applied to Paris, refers almost always to the municipal arrondissements listed below. The number of the arrondissement is indicated by the last two digits in most Parisian postal codes (75001 up to 75020).

Paris during the Belle Époque

In Short

Paris in the Belle Époque, between 1871 and 1914, from the beginning of the Third French Republic until the First World War, saw the construction of the Eiffel Tower, the Paris Métro, the completion of the Paris Opera, and the beginning of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on Montmartre. Three universal expositions in 1878, 1889 and 1900 brought millions of visitors to Paris to see the latest in commerce, art and technology. Paris was the scene of the first public projection of a motion picture, and the birthplace of the Ballets Russes, Impressionism and Modern Art.

The expression Belle Époque came into use after the First World War, a nostalgic term for what seemed a simpler time of optimism, elegance and progress.

Paris 1900: La Belle Époque, l'Exposition Universelle, l'Art Nouveau (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8MZGusqwKPo)

Rebuilding after the Commune

After the violent end of the Paris Commune in May 1871, the city was governed by martial law, under the strict surveillance of the national government. The government and parliament did not return to the city from Versailles until 1879, though the Senate returned earlier to its home in the Luxembourg Palace.

The end of the Commune also left the city's population deeply divided. Gustave Flaubert described the atmosphere in the city in early June 1871: "One half of the population of Paris wants to strangle the other half, and the other half has the same idea; you can read it in the eyes of people passing by." But that sentiment soon became secondary to the need to reconstruct the buildings that had been destroyed in the last days of the Commune. The Communards had burned the Hôtel de Ville (including all the city archives), the Tuileries Palace, the Palais de Justice, the Prefecture of Police, the Ministry of Finances, the Cour des Comptes, the State Council building at the Palais-Royal, and many others. Several streets, particularly the rue de Rivoli, had also been badly damaged by the fighting. The column in Place Vendôme had been toppled, on a suggestion from Gustave Courbet, a supporter of the Commune. On top of the reconstruction, the new government was obliged to pay 210 million francs in gold to the victorious German Empire as reparations for the disastrous Franco-Prussian War of 1870. On August 4, 1871, at the first meeting of the city council after the Commune, the new Prefect of the Seine, Léon Say, put forward a plan to borrow 350 million francs for reconstruction and to pay Germany. The city's bankers and businessmen quickly raised the money, and the reconstruction was soon underway.

The Conseil d'État and Palais de la Légion d'Honneur (Hôtel de Salm) were rebuilt in their original style. The new Hôtel de Ville was given a more picturesque Renaissance style than the original, borrowed from the Château de Chambord in the Loire Valley, with a facade decorated with statues of outstanding personages who contributed to the history and fame of Paris. The destroyed Ministry of Finance on the rue de Rivoli was replaced by a grand hotel, while the Ministry moved into the Richelieu wing of the Louvre, where it remained until 1989. The ruined Cour des Comptes on the left bank was replaced by the gare d'Orléans, also known under the name gare d'Orsay, now the Museé d'Orsay. The one difficult decision was the Tuileries Palace; built in the 16th century by Marie de' Medici, a royal and imperial residence. The interior had been entirely destroyed by the fire, but the walls were still largely intact, and remained standing for ten years, while the fate of the ruins was debated. Baron Haussmann, in retirement, appealed for a restoration of the building as an historic monument, and it was proposed to turn it into a new museum of modern art. But, in 1881, the new Chamber of Deputies, more sympathetic to the Commune than previous governments, decided that it was too much a symbol of the monarchy, and had the walls pulled down.

On 23 July 1873, the National Assembly endorsed the project of building a basilica at the site where the uprising of the Paris Commune had begun; it was intended to atone for the sufferings of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune. The Basilica of Sacré-Cœur was built in the neo-Byzantine style, and paid for by public subscription. It was not finished until 1919, and quickly became one of the most recognizable landmarks in Paris.

The Parisians

The population of Paris was 1,851,792 in 1872, at the beginning the Belle Époque. By 1911, it reached 2,888,107, higher than today's (2015) population. At the end of the Second Empire and the beginning of the Belle Époque, between 1866 and 1872, the population of Paris grew only 1.5 percent. The population surged by 14.09 percent between 1876 and 1881, then slowed down again to 3.3 percent between 1881 and 1886. After that it grew very slowly until the end of the Belle Époque, reaching its historic high of almost three million persons in 1921, before beginning a long decline until the early 21st century.

In 1886, about one-third of the population of Paris (35.7 percent) had been born in Paris. More than half 56.3 percent) had been born in other departments of France, and about eight-percent outside France. In 1891, Paris was the most cosmopolitan of European capital cities, with seventy-five foreign-born residents for every thousand inhabitants, compared with twenty-four for Saint-Petersburg, twenty-two for London and Vienna, and eleven for Berlin. The largest communities of immigrants were Belgians, Germans, Italians and Swiss, with between twenty and twenty-eight thousand persons from each country, followed by about ten thousand from Great Britain and equal number from Russia; eight thousand from Luxembourg; six thousand South Americans; and five thousand Austrians. There were 445 Africans, 439 Danes, 328 Portuguese and 298 Norwegians. Certain nationalities were concentrated in specific professions; Italians in the businesses of making ceramics, shoes, sugar and conserves; Germans in leather-working, brewing, baking and charcuterie. The Swiss and Germans were predominant in businesses making watches and clocks, and also accounted for a large proportion of the domestic servants.

The remnants of old Paris aristocracy and the new aristocracy of bankers, financiers and entrepreneurs mostly had their residences in the 8th arrondissement, from the Champs-Élysées to the Madeleine), in the quartier de l'Europe and butte Chaillot; the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, the quartier Saint-Georges, from rue Vivienne and the Palais-Royal to Roule and the plain of Monceau. On the right bank, they lived in Le Marais; on the left bank, on the south of the Latin quarter, at N(Notre-Dame-des-Champs and Odéon; near Les Invalides and at the École Militaire. The less affluent shop owners lived from porte Saint-Denis to Les Halles, to the west of boulevard de Sébastopol. The middle class employees of enterprises, small businesses and government lived closer to the center, along the Grands boulevards, in the 10th arrondissement, in the 1st and 2nd arrondissements near the Bourse (Stock Exchange), in the Sentier quarter near Les Halles, and in Le Marais.

Under Napoleon III, Haussmann had demolished the poorest, most crowded and historical neighborhoods in the center of the city to make room for the new boulevards and squares. The working-class Parisians had moved out of the center toward the edges of the city; particularly to Belleville and Ménilmontant in the east, to Clignancourt and Grandes Carrières to the north, and on the left bank to the area around the Gare d'Austerlitz, Javel and Grenelle, usually to neighborhoods that were close to their places of work. Small quarters of working-class Parisians still remained in the center of the city, on the sides of the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève in the Latin Quarter, near the Sorbonne and the Jardin des Plantes, and along the covered Bièvre River, where the tanneries had been located for centuries.

Paris was both the richest and poorest city in France. Twenty-four percent of the wealth in France was found in the Seine department, but fifty-five percent of burials of Parisians were made in the section for those unable to pay. In 1878, two-thirds of Parisians paid less than 300 francs a year for their lodging, a very small amount at the time. An 1882 study of Parisians, based on funeral costs, concluded that twenty-seven percent of Parisians were upper or middle class, while seventy-three percent were poor or indigent. Incomes varied greatly according to the neighborhood: in the 8th arrondissement, there were eight poor persons for ten upper or middle class residents; in the 13th, 19th and 20th arrondissements, there were seven or eight poor for every well-off resident.

The Apaches of Paris

Apaches was a term that was introduced by Paris newspapers in 1902 for young Parisians who engaged in petty crime and sometimes fought each other or the police. They usually lived in Belleville and Charonne. Their activities were described in lurid terms by the popular press, and they were blamed for all varieties of crime in the city. In September 1907, the newspaper Le Gaulois described an Apache as "the man who lives on the margin of society, ready to do anything, except to take a regular job, the miserable who breaks in a doorway, or stabs a passer-by for nothing, just for pleasure.

Population

- -- City (2,891,020) - 1931 census

- -- Urban (5,674,419) - 1931 census

Arenas

Attractions

- -- Casino de Paris -- The Casino located at 16, rue de Clichy, in the 9th arrondissement, is one of the well known music halls of Paris, with a history dating back to the 18th century. Contrary to what the name might suggest, it is a performance venue, not a gambling house.

Bars and Clubs

Cemeteries

City Government

Crime

Citizens of the City

Corax of Paris

Current Events

Fortifications

Galleries

Gallû of Paris =

Holy Ground

Hospitals

Hotels & Hostels

Landmarks

Law Enforcement

Lupines of Paris

Bone Gnawers

Get of Fenris

Glass Walkers

Shadow Lords

Mages of Paris

Technocracy

Tradition

Mass Media

Monuments

Museums

Parks

Private Residences

Restaurants

Ruins

Schools

Shopping

Telecommunications

Theaters

Transportation

Vampires of the City

The Legacy of Villon: The Edicts

"The Edicts are written in English for understanding, and in French for mood purpose."

L'Art / The Art

Vous ne devrez ni voler, ni détruire, ni altérer un Objet d'Art sans l'Autorisation de l'Ancien parmi les Anciens. Aucun

Objet d'Art ne doit sortir du Territoire de France sans l'Autorisation de l'Ancien parmi les Anciens.

You must not steal, destroy, or alter an Object of Art without the Authorization of the Eldest among you.

No Object of Art is to exit the domain of France without the Authorization of the Eldest among you.

L'Elysée / The Elysium

Les Lieux protégé par l'Elysée ne pourront être le théatre de violence, ni de la Chasse. Provoquer la violence ou Chasser

dans l'Elysée sans l'Autorisation de l'Ancien parmi les Anciens est passible d'une Chasse de Sang. Par mesure de sécurité,

l'accès de certains Elysées sera réglementé.

Grounds protected by the Elysium will not be sullied by violence of hunt. Provoke violence or hunting in an Elysium

without the authorization of the Eldest among you can be punished by the Blood Hunt. For security reasons, the access to

some Elysiums will be limited.

L'Ordre / Order

L'ordre doit être garanti par le Prince, qui s'approprie donc de manière exclusive les moyens d'assurer

l'ordre et le bien-être de la Famille comme du Bétail. Il est par consécquent formellement interdit d'influencer

les forces de polices et les forces armées.

Les Masques et les Veilleurs, étant les representants du Prince, ne sont pas soumis à cet Edit.

Order is to be guarranteed by the Prince, who thus gather exclusively for himself the means to warrant the order and well

being of Kindred and Kine. Thus it is strictly forbidden to influence the police and army forces.

The Masques, being the representatives of the Prince, are not submitted to this Edict.

Diablerie / Diablerie

La Diablerie est un acte infâme indigne de notre Condition. Tout Caïnite convaincu de Diablerie sera passible d'une Chasse

de Sang, et ce, quel qu'ait été le Calice, ou l'endroit du crime.

Diablerie is an atrocious action under our condition. Any Kindred guilty of Diablerie can be Blood Hunted,

no matter who was the victim and where it happened.

L'Amaranthe / The Amaranth

Ceux qui se seront montré particulièrement indigne de leur Sang pourront voir leur Sang arraché par l'Amaranthe. Seuls

ceux qui auront été dignes des Traditions et Edits de Paris pourront se voir peut-être accordé par l'Ancien parmis les

Anciens, l'Amaranthe.

Those who acted in ways unworthy of their Blood can be subject to the Amaranth. Those who acted in ways worthy of their

Blood and of the Traditions and Edicts can be given the right of Amaranth by the Eldest among you.

La Magye / The Magick

Pratiquer les rituels magiques en présence d'un Mage est strictement interdit, tout comme tout contact avec eux.

Leur guerre d'ascension n'est pas la nôtre. Clan Tremere Le retour à Paris est conditionné par le comportement de leurs membres.

Les Veilleurs ne sont pas soumis à cet édit.

Praticing magic rituals in presence of a Mage is strictly forbidden, as is any contact with them. Their Ascensíon war is not our own. Clan Tremere Returning to

Paris is conditioned by the behaviour of their members.

The Veilleurs are not submitted to this Edict.

Assamites

Brujah

- -- Benedicte Dalouche -- Currently in Berlin...but wanting to return.

- -- L'Homme de Peu de Foi

- -- Saint Just 8th Generation, childe of Robin Leeland, sire of Karl.

- -- Thomas Frère(Thomas, Brother); 6th Generation Duc of the Brujah.

The Bâtards/ Catiff

Daughters of Cacophony

Gangrel

Malkavian

Nosferatu

Toreador

- - Francois Villon -- Domain: The Louvre {Location: Right Bank of the Seine in the 1st arrondissement.}

- - Arnaud -- Domain: Club Elysée {Location: 8th Arrondissement}

- - Carla Gagnon -- Domain: Église de Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet {Location: 5th Arrondissement}

- - Maxime -- Domain: Saint-Georges -- A neighborhood of Pigalle -- Maxime has a loft above the vaunted SACEM building that he uses as his haven. {Location: 9th Arrondissement}

- - Bernard -- Domain: The Louvre {Location: Right Bank of the Seine in the 1st arrondissement.} -- As the Seneschal of Paris, Bernard resides with his sire in the Louvre.

- - Chevalier d'Eglantine -- Domain: Les Invalides {Location: 7th Arrondissement}

- Merevith

- - Elle Emilie Nicoline

- - Lazlo Guerin -- Domain: Palais Bourbon {Location: 7th Arrondissement}

- - Florient (Deceased)

- - Versancia

- - Violetta Desjardins

- - Arnaud -- Domain: Club Elysée {Location: 8th Arrondissement}

Tremere

- -- Lazare Monet -- Creator of La Transsubstantiation de la Cuisine.

True Brujah

Ventrue

Websites

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_between_the_Wars_(1919%E2%80%931939)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belle_%C3%89poque

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_in_the_Belle_%C3%89poque