Paris - La Belle Époque: Difference between revisions

| Line 276: | Line 276: | ||

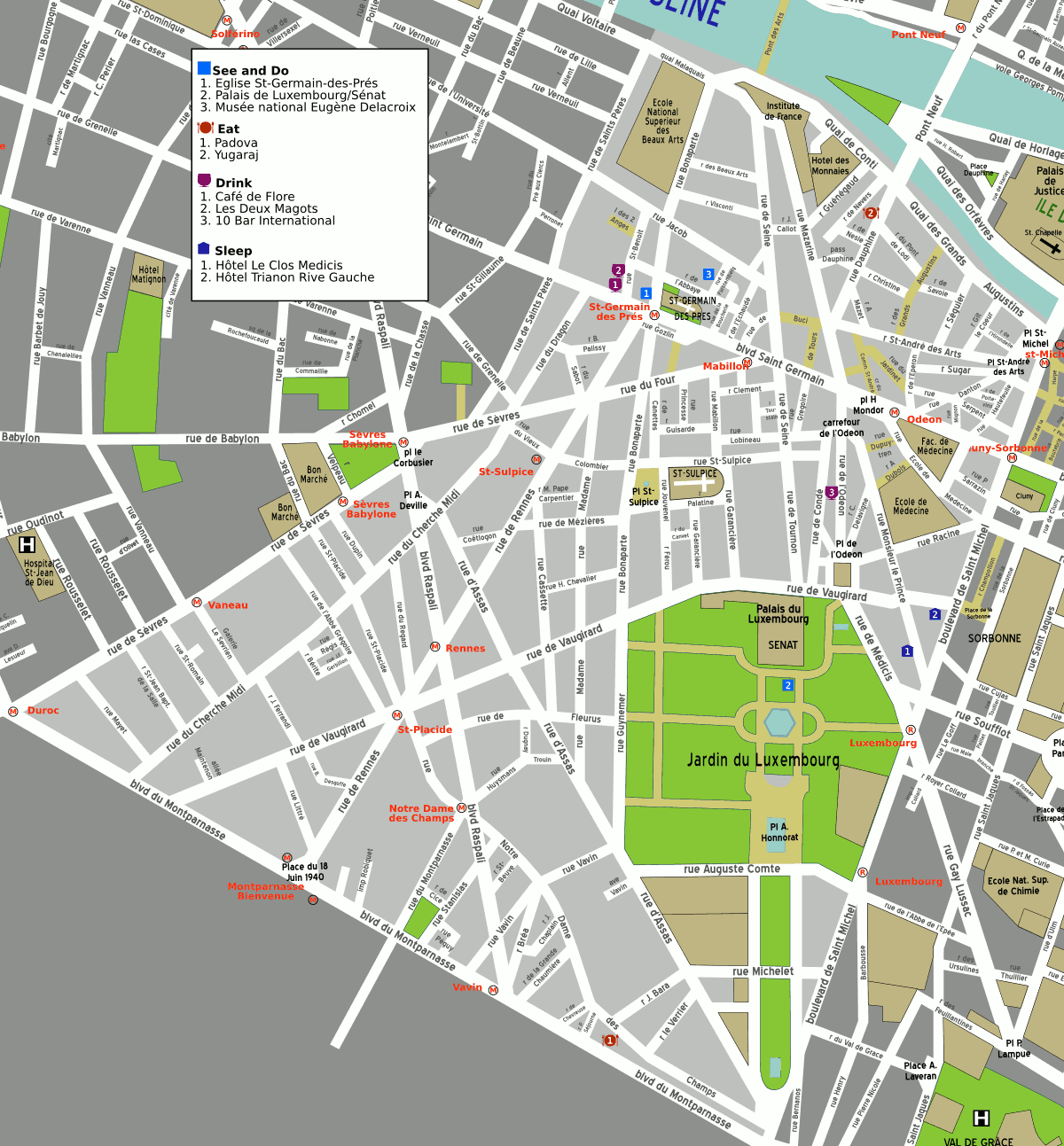

=== '''6th Arrondissment''' === | === '''6th Arrondissment''' === | ||

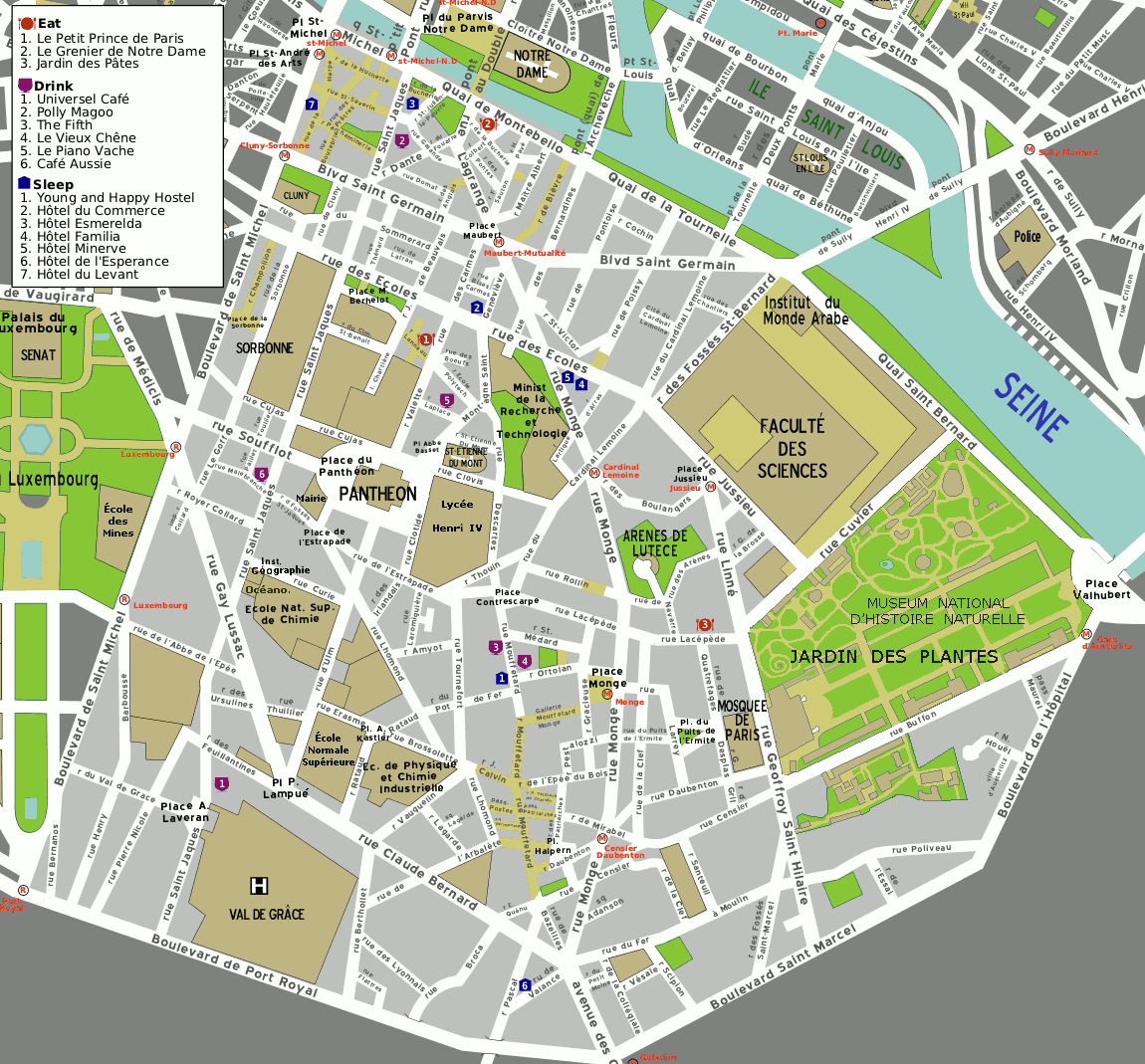

[[]] | [[File:Paris 6th.png]] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 21:22, 26 December 2017

- Past Imperfect -PLBE- Paris - 1933 -PLBE- Paris

Quote

"Paris was a universe whole and entire unto herself, hollowed and fashioned by history; so she seemed in this age of Napoleon III with her towering buildings, her massive cathedrals, her grand boulevards and ancient winding medieval streets--as vast and indestructible as nature itself. All was embraced by her, by her volatile and enchanted populace thronging the galleries, the theaters, the cafes, giving birth over and over to genius and sanctity, philosophy and war, frivolity and the finest art; so it seemed that if all the world outside her were to sink into darkness, what was fine, what was beautiful, what was essential might there still come to its finest flower. Even the majestic trees that graced and sheltered her streets were attuned to her--and the waters of the Seine, contained and beautiful as they wound through her heart; so that the earth on that spot, so shaped by blood and consciousness, had ceased to be the earth and had become Paris."

― Anne Rice, Interview with the Vampire

Paris during the Belle Époque

In Short

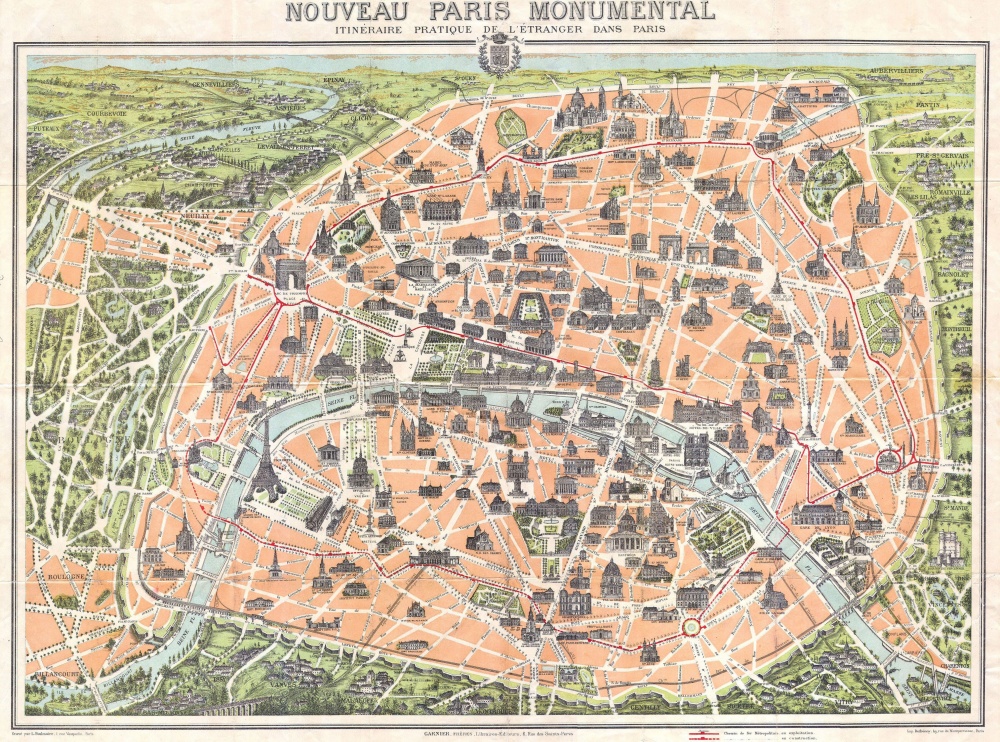

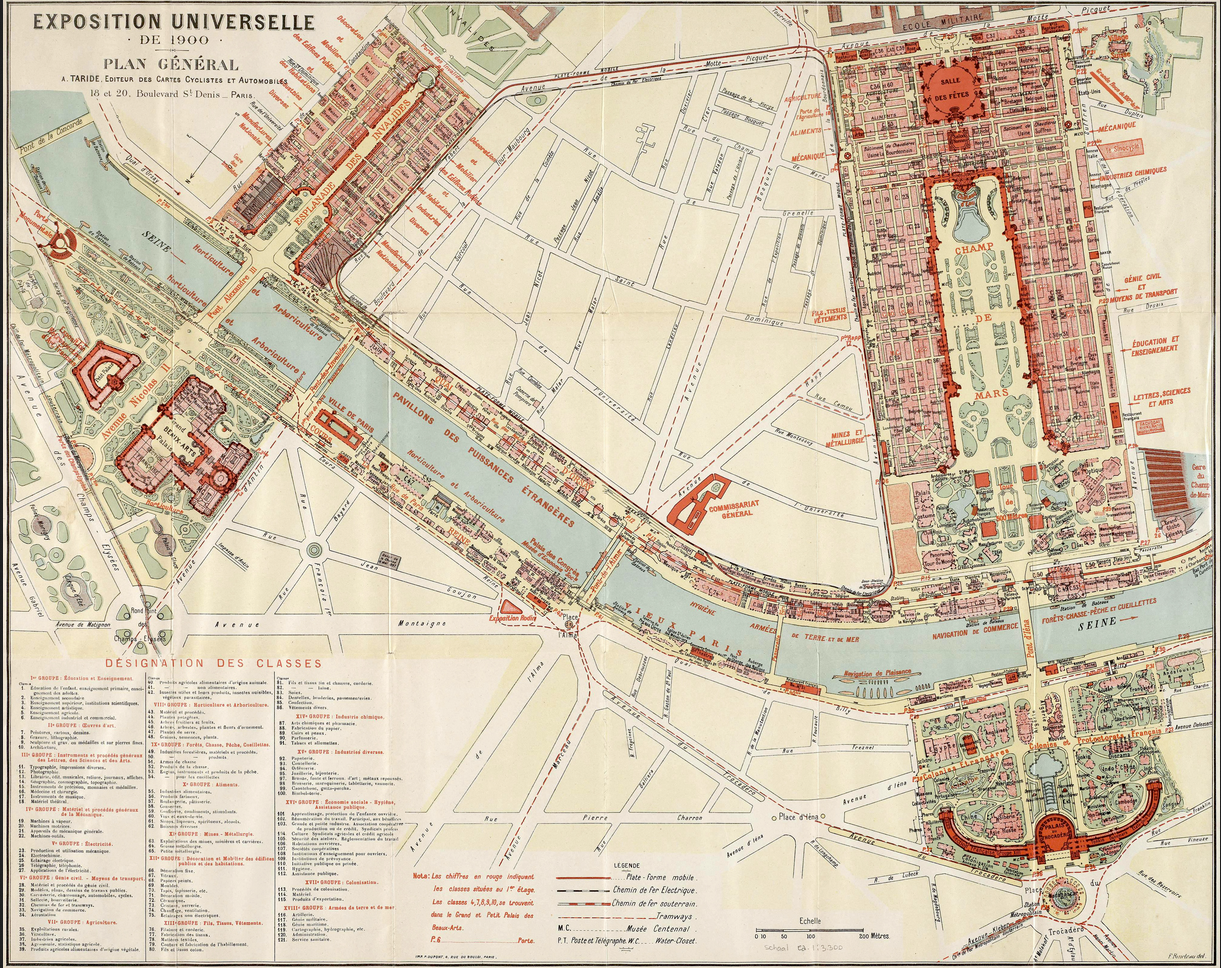

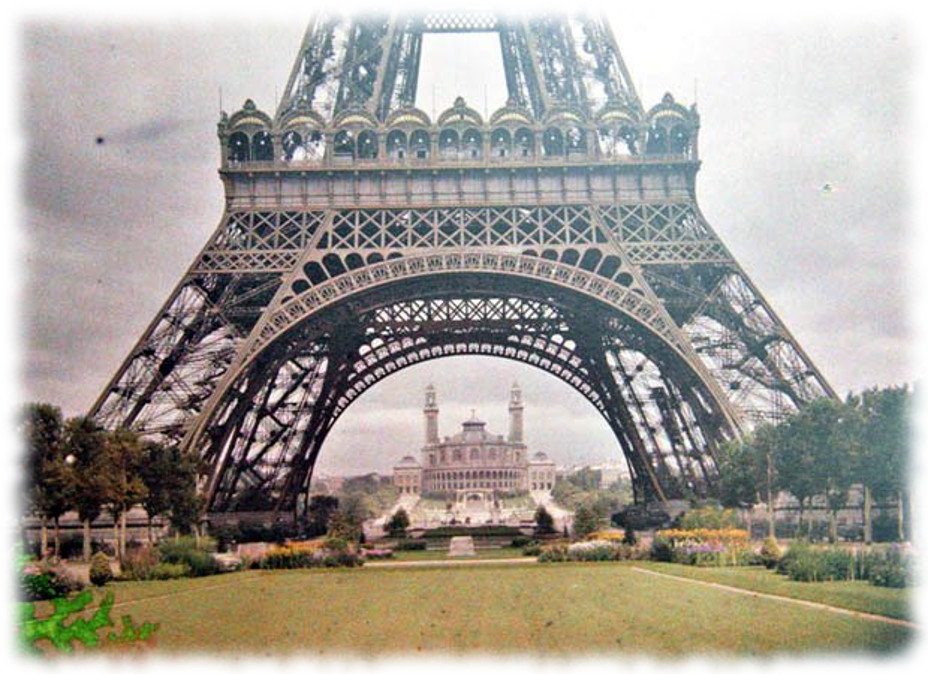

Paris in the Belle Époque, between 1871 and 1914, from the beginning of the Third French Republic until the First World War, saw the construction of the Eiffel Tower, the Paris Métro, the completion of the Paris Opera, and the beginning of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on Montmartre. Three universal expositions in 1878, 1889 and 1900 brought millions of visitors to Paris to see the latest in commerce, art and technology. Paris was the scene of the first public projection of a motion picture, and the birthplace of the Ballets Russes, Impressionism and Modern Art.

The expression Belle Époque came into use after the First World War, a nostalgic term for what seemed a simpler time of optimism, elegance and progress.

Paris 1900: La Belle Époque, l'Exposition Universelle, l'Art Nouveau (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8MZGusqwKPo)

Appearance

Rebuilding after the Commune

After the violent end of the Paris Commune in May 1871, the city was governed by martial law, under the strict surveillance of the national government. The government and parliament did not return to the city from Versailles until 1879, though the Senate returned earlier to its home in the Luxembourg Palace.

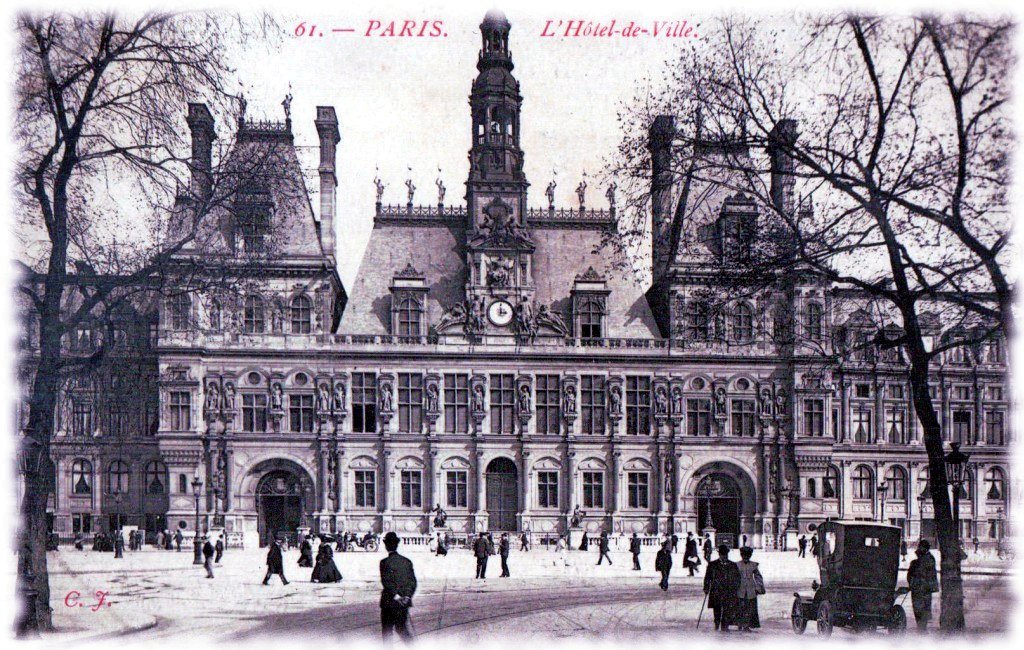

The end of the Commune also left the city's population deeply divided. Gustave Flaubert described the atmosphere in the city in early June 1871: "One half of the population of Paris wants to strangle the other half, and the other half has the same idea; you can read it in the eyes of people passing by." But that sentiment soon became secondary to the need to reconstruct the buildings that had been destroyed in the last days of the Commune. The Communards had burned the Hôtel de Ville (including all the city archives), the Tuileries Palace, the Palais de Justice, the Prefecture of Police, the Ministry of Finances, the Cour des Comptes, the State Council building at the Palais-Royal, and many others. Several streets, particularly the rue de Rivoli, had also been badly damaged by the fighting. The column in Place Vendôme had been toppled, on a suggestion from Gustave Courbet, a supporter of the Commune. On top of the reconstruction, the new government was obliged to pay 210 million francs in gold to the victorious German Empire as reparations for the disastrous Franco-Prussian War of 1870. On August 4, 1871, at the first meeting of the city council after the Commune, the new Prefect of the Seine, Léon Say, put forward a plan to borrow 350 million francs for reconstruction and to pay Germany. The city's bankers and businessmen quickly raised the money, and the reconstruction was soon underway.

The Conseil d'État and Palais de la Légion d'Honneur (Hôtel de Salm) were rebuilt in their original style. The new Hôtel de Ville was given a more picturesque Renaissance style than the original, borrowed from the Château de Chambord in the Loire Valley, with a facade decorated with statues of outstanding personages who contributed to the history and fame of Paris. The destroyed Ministry of Finance on the rue de Rivoli was replaced by a grand hotel, while the Ministry moved into the Richelieu wing of the Louvre, where it remained until 1989. The ruined Cour des Comptes on the left bank was replaced by the gare d'Orléans, also known under the name gare d'Orsay, now the Museé d'Orsay. The one difficult decision was the Tuileries Palace; built in the 16th century by Marie de' Medici, a royal and imperial residence. The interior had been entirely destroyed by the fire, but the walls were still largely intact, and remained standing for ten years, while the fate of the ruins was debated. Baron Haussmann, in retirement, appealed for a restoration of the building as an historic monument, and it was proposed to turn it into a new museum of modern art. But, in 1881, the new Chamber of Deputies, more sympathetic to the Commune than previous governments, decided that it was too much a symbol of the monarchy, and had the walls pulled down.

On 23 July 1873, the National Assembly endorsed the project of building a basilica at the site where the uprising of the Paris Commune had begun; it was intended to atone for the sufferings of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune. The Basilica of Sacré-Cœur was built in the neo-Byzantine style, and paid for by public subscription. It was not finished until 1919, and quickly became one of the most recognizable landmarks in Paris.

Architecture

The architectural style of the Belle Époque was eclectic, and sometimes combined elements of several different styles. While the structures of the new buildings were resolutely modern, using iron frames and reinforced concrete, the façades ranged from the Romano-Byzantine style of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on Montmartre, to the strange neo-Moorish Palais du Trocadéro, to the nouveau Renaissance style of the new Hôtel de Ville, to the exuberant reinvention of French of the 17th and 18th centuries classicism in the Grand Palais and Petit Palais and the Gare d'Orsay, decorated with domes, colonnades, mosaics and statuary. The most innovative buildings of the period were the Gallery of Machines at the 1889 exposition, and the new railroad stations and department stores: their classical exteriors concealed very modern interiors, with large open spaces and large glass skylights made possible by the new engineering techniques of the period. The Eiffel Tower shocked many traditional Parisians, both because of its appearance and because it was the first building in Paris taller than the cathedral of Notre-Dame.

The Art nouveau became the outstanding style of the period, particularly associated with the metro station entrances designed by Hector Guimard, and with a handful of buildings, including Guimard's Castel Béranger (1889) at 14 rue La Fontaine and the Hôtel Mezzara (1910) in the 16th arrondissement. The enthusiasm for Art nouveau metro station entrances did not last long; in 1904 it was replaced at the Opera metro by a less exuberant "modern" style. Beginning in 1912, all the Guimard metro entrances were replaced with functional entrances without decoration.

A revolutionary new building material, reinforced concrete, appeared at the beginning of the 20th century and quietly began to change the face of Paris. The first church built in the new material was Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre, at 19 rue des Abbesses at the foot of Montmartre. The architect was Anatole de Baudot, a student of Viollet-le-Duc. The nature of the revolution was not evident, because Baudot faced the concrete with brick and ceramic tiles in a colorful Art nouveau style, with stained glass windows in the same style.

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1913) is another architectural landmark of the period, one of the few Paris buildings in the Art deco style. Designed by Auguste Perret, it was also built of reinforced concrete, and decorated by some of the leading artists of the era; bas-reliefs on the façade by Antoine Bourdelle, a dome by Maurice Denis, and paintings in the interior by Édouard Vuillard. It was the setting in 1913 for one of the major musical events of the Belle Époque, the first season of the Ballets Russes and the premiere of Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring.

Bridges

Eight new bridges were put across the Seine during the Belle Époque. The pont Sully, built in 1876, replaced two foot bridges which had connected the Île Saint-Louis to the right and left bank. The pont de Tolbiac was built in 1882], connecting the left bank with Bercy. The Pont Mirabeau, made famous in a poem by Apollinaire, was dedicated in 1895. Three bridges were built for the 1900 Exposition: the pont Alexandre-III, dedicated by the Czar Nicholas II of Russia in 1896, which connected the left bank with the grand exposition halls of the Grand Palaisand Petit Palais; the passerelle Debilly, a foot bridge which linked two sections of the Exposition; and a railroad bridge between Grenelle and Passy. Two more bridges were dedicated in 1905; the pont de Passy (now the pont de Bir-Hakeim), and the viaduc d'Austerlitz, crossed by the metro.

Streets and Boulevards

The construction of the new boulevards and streets begun by Napoleon III and Haussmann had been much criticized by Napoleon's opponents near the end of the Second Empire, but the government of the Third Republic continued his projects. The avenue de l'Opéra, boulevard Saint-Germain, avenue de la République, boulevard Henry-IV and avenue Ledru-Rollin were all completed essentially as Haussmann had planned them by 1889. After 1889, the pace of construction slowed down; boulevard Raspail was finished, rue Réaumur was extended, and several new streets were created on the left bank; rue de la Convention, rue de Vouillé, rue d'Alésia, and rue de Tolbiac. On the right bank, rue Étienne-Marcel was the last of the Haussmann projects to be completed before the First World War.

While the streets planned by Haussmann were completed, the strict uniformity of façades and building heights imposed by Haussmann was gradually modified. Buildings became much larger and deeper, with two apartments on each floor facing the street and others facing only onto the courtyard. The new buildings often had ornamental rotundas or pavilions on the corners, and highly ornamental roof designs and gables. In 1902, maximum building heights were increased to 52 meters. With the advent of elevators, the most desirable apartments were no longer on the lowest floors, but on the highest floors, where there was more light, nicer view and less noise. With the arrival of automobiles and the beginning of traffic noise on the streets, the bedrooms moved to the back of the apartment, onto the courtyard.

The façades also changed from the strict symmetry of Haussmann: bay and bow windows appeared, and undulating façades. Eclectic façades became popular, mixing Louis XIV, Lous XV and Louis XVI styles, and then, with the Art nouveau, floral patterns. The most striking examples of the new architecture were the Castel Béranger on rue La Fontaine and the Hôtel Lutetia. Between 1898 and 1905, the city organized eight competitions for the most imaginative building façades; variety was given precedence over uniformity.

Street Lighting

At the beginning of the Belle Époque Paris was lit by a constellation of thousands of gaslights, which were often admired by foreign visitors, and helped give the city its nickname Ville-Lumiére, the "City of Light". In 1870, there were 56,573 used exclusively to light the city streets. The gas was produced by ten enormous factories around the edge of the city, located near the circle of fortifications, and was distributed in pipes installed under the new boulevards and streets. The street lights were placed every twenty meters on the Grands Boulevards. At a predetermined minute after nightfall, a small army of 750 allumeurs in uniform, carrying long poles with small lamps at the end, went out into the streets, turned on a pipe of gas inside each lamppost, and lit the lamp. The entire city was illuminated within forty minutes. The Arc de Triomphe was crowned with a ring of gaslights, and the Champs-Élysées was lined with ribbons of white light.

One of the major urban innovations in Paris was the introduction of electric street lights, to coincide with the Universal Exposition of 1878. The first streets lit were the Avenue de l'Opéra and the Place de l'Étoile, around the Arc de Triomphe. In 1881, electric street lights were added along the Grands Boulevards. Electric lighting came much more slowly for residences and businesses in some Paris neighborhoods. While in 1905 electric lights lined the Champs Élysées, there was no electric lines for households in the 20th arrondissement.

City Device

Climate

Paris has a typical Western European oceanic climate which is affected by the North Atlantic Current. The overall climate throughout the year is mild and moderately wet. Summer days are usually moderately warm and pleasant with average temperatures hovering between 15 and 25 °C (59 and 77 °F), and a fair amount of sunshine. Each year, however, there are a few days where the temperature rises above 30 °C (86 °F). Some years have even witnessed some long periods of harsh summer weather, such as the heat wave of 2003 where temperatures exceeded 30 °C (86 °F) for weeks, surged up to 39 °C (102 °F) on some days and seldom cooled down at night. More recently, the average temperature for July 2011 was 17.6 °C (63.7 °F), with an average minimum temperature of 12.9 °C (55.2 °F) and an average maximum temperature of 23.7 °C (74.7 °F).

Spring and autumn have, on average, mild days and fresh nights, but are changing and unstable. Surprisingly warm or cool weather occurs frequently in both seasons. In winter, sunshine is scarce; days are cold but generally above freezing with temperatures around 7 °C (45 °F). Light night frosts are however quite common, but the temperature will dip below −5 °C (23 °F) for only a few days a year. Snowfall is uncommon, but the city sometimes sees light snow or flurries with or without accumulation.

Rain falls throughout the year. Average annual precipitation is 652 mm (25.7 in) with light rainfall fairly distributed throughout the year. The highest recorded temperature is 40.4 °C (104.7 °F) on July 28, 1948, and the lowest is a −23.9 °C (−11.0 °F) on December 10, 1879.

Demonym

Parisian

Economy

The economy of Paris suffered an economic crisis in the early 1870s, followed by a long, slow recovery; then a period of rapid growth beginning in 1895 until the First World War. Between 1872 and 1895, in the capital, 139 large enterprises closed their doors, particularly textile and furniture factories, those in the metallurgy sector, and printing houses, four industries which for sixty years had been the major employers in the city. Most of these enterprises had employed, each, between 100 and 200 workers. Half of the large enterprises on the center of the city's right bank moved out, in part because of the high cost of real estate, and also to get better access to transportation on the river and railroads. Several moved to less-expensive areas at the edges of the city, around Monparnasse and La Salpêtriére, while others went to the 18th arrondissement, La Villette and the Canal Saint-Denis, to be closer to the river ports and the new railroad freight yards, to Picpus and Charonne in the southeast, or near Grenelle and Javel in the southwest. The total number of enterprises in Paris dropped from 76,000 in 1872 to 60,000 in 1896, while in the suburbs their number grew from 11,000 to 13,000. In the heart of Paris, many workers were still employed in traditional industries such as textiles (18,000 workers), garment production (45,000 workers), and in the new industries which required highly skilled workers, such as mechanical and electrical engineering, and automobile manufacturing.

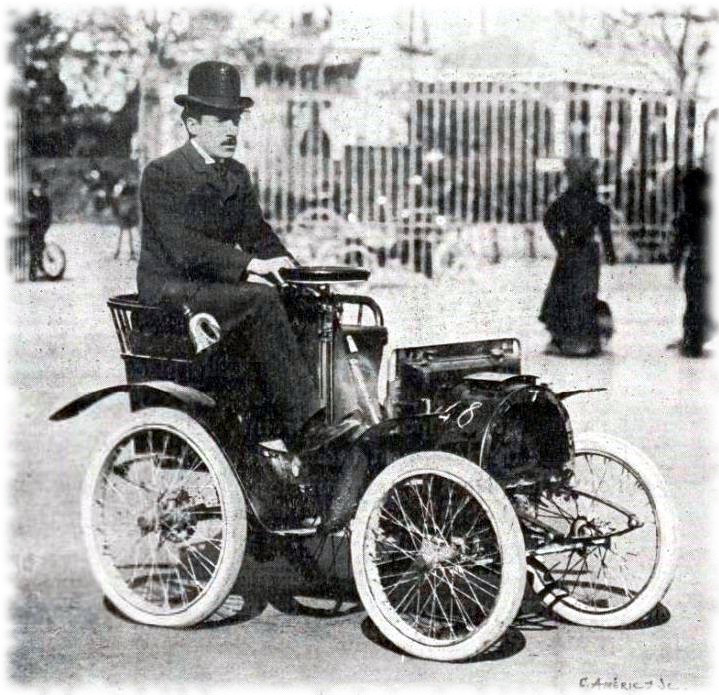

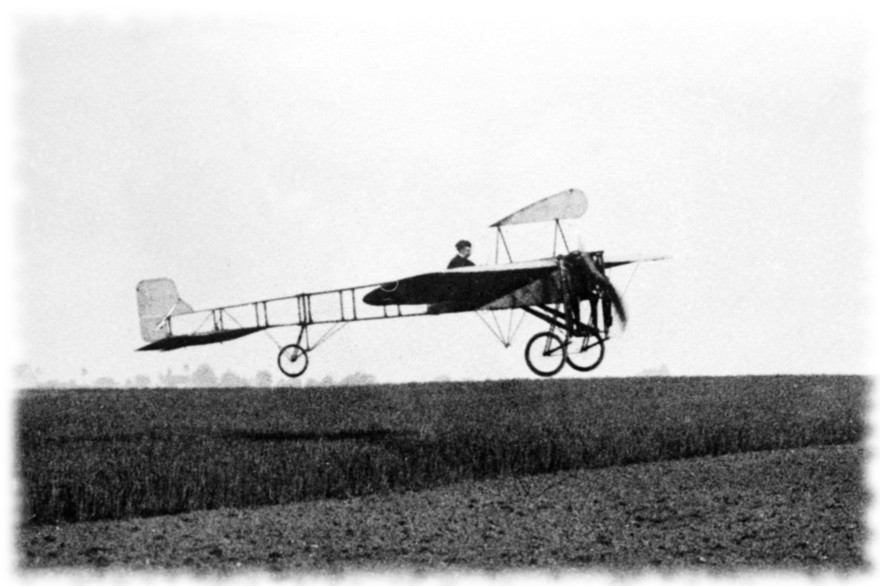

Three New Industries

Three major new French industries were born in and around Paris at almost the same time, taking advantage of the abundance of skilled engineers and technicians, and money from Paris banks. They produced the first French automobiles, aircraft, and motion pictures. In 1898, Louis Renault and his brother Marcel built their first automobile, and founded a new company to produce them. They established their first factory at Boulogne-Billancourt, just outside the city, and made the first French truck in 1906 In 1908, they built 3,595 cars, making them the largest car manufacturer in France. They received an important contract to make taxicabs for the largest Paris taxi company. When the first World War began in 1914, the Renault taxis of Paris were mobilized to carry French soldiers to the front at the First Battle of the Marne.

The French aviation pioneer Louis Blériot also established a company, Blériot Aéronautique, on boulevard Victor-Hugo in Neuilly, where he manufactured the first French airplanes. On 25 July 1909, he became the first man to fly across the English Channel. Blériot moved his company to Buc, near Versailles, where he established a private airport and a flying school. In 1910, he built the Aérobus, one of the first passenger aircraft, which could carry seven persons, the most of any aircraft of the time.

The Lumière Brothers had given the first projected showing of a motion picture La Sortie de l'usine Lumière, at the Salon Indien du Grand Café of the Hôtel Scribe, boulevard des Capucines, on December 28, 1895. A young French entrepreneur, Georges Méliés, attended the first showing, and asked the Lumière brothers for a iicense to make films. The Lumière Brothers politely declined, telling him that the cinema was for scientific purposes, and had no commercial value. Méliés persisted, and established his own small studio in 1897 in Montreuil, just east of Paris. He became a producer, director, scenarist, set designer and actor, and made hundreds of short films, including the first science-fiction film, A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage dans la Lune), in 1902. Another French cinema pioneer and producer Charles Pathé, also built a studio in Montreuil, then moved to rue des Vignerons in Vincennes, east of Paris. His chief rival in the early French film industry, Léon Gaumont, opened his first studio at about the same time at rue des Alouettes in the 19th arrondissement, near the Buttes-Chaumont.

Geography

Paris is located in northern central France. By road it is 450 kilometres (280 mi) south-east of London, 287 kilometres (178 mi) south of Calais, 305 kilometres (190 mi) south-west of Brussels, 774 kilometres (481 mi) north of Marseilles, 385 kilometres (239 mi) north-east of Nantes, and 135 kilometres (84 mi) south-east of Rouen. Paris is located in the north-bending arc of the river Seine, spread widely on both banks of the river, and includes two inhabited islands, the Île Saint-Louis and the larger Île de la Cité, which forms the oldest part of the city. The river’s mouth on the English Channel (La Manche) is about 233 mi (375 km) downstream of the city. Overall, the city is relatively flat, and the lowest point is 35 m (115 ft) above sea level. Paris has several prominent hills, of which the highest is Montmartre at 130 m (427 ft). Montmartre gained its name from the martyrdom of Saint Denis, first bishop of Paris atop the "Mons Martyrum" (Martyr's mound) in 250 A.D.

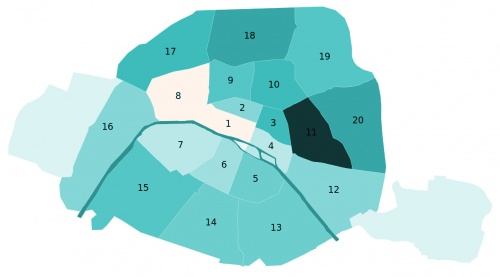

Excluding the outlying parks of Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes, Paris occupies an oval measuring about 87 km2 (34 sq mi) in area, enclosed by the 35 km (22 mi) ring road, the Boulevard Périphérique. The city's last major annexation of outlying territories in 1860 not only gave it its modern form but also created the twenty clockwise-spiralling arrondissements (municipal boroughs). From the 1860 area of 78 km2 (30 sq mi), the city limits were expanded marginally to 86.9 km2 (33.6 sq mi) in the 1920s. In 1929, the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes forest parks were officially annexed to the city, bringing its area to about 105 km2 (41 sq mi). The metropolitan area of the city is 2,300 km2 (890 sq mi).

Arrondissements

Introduction

The city of Paris is divided into twenty arrondissements municipaux, administrative districts, more simply referred to as arrondissements. These are not to be confused with departmental arrondissements, which subdivide the 101 French départements. The word "arrondissement", when applied to Paris, refers almost always to the municipal arrondissements listed below. The number of the arrondissement is indicated by the last two digits in most Parisian postal codes (75001 up to 75020).

1st Arrondissment

Situated principally on the right bank of the River Seine, it includes the west end of the Île de la Cité. The arrondissement is one of the oldest in Paris, the Île de la Cité having been the heart of the city of Lutetia, conquered by the Romans in 52 BC, while some parts on the right bank (including Les Halles) date back to the early Middle Ages.

It is the least populated of the city's arrondissements and one of the smallest by area, a significant part of which is occupied by the Louvre Museum and the Tuileries Gardens. Much of the remainder of the arrondissement is dedicated to business and administration.

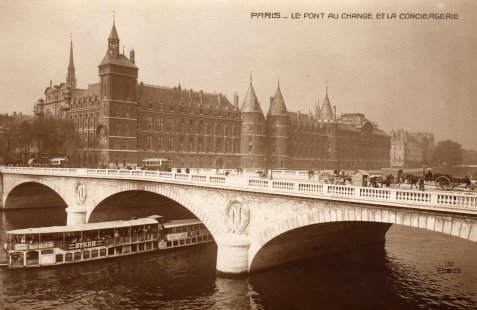

Bridges

- Pont Neuf: is the oldest standing bridge across the river Seine in Paris, France. It stands by the western (downstream) point of the Île de la Cité, the island in the middle of the river that was, between 250 and 225 BC, the birthplace of Paris, then known as Lutetia, and during the medieval period, the heart of the city.

The name Pont Neuf was given to distinguish it from older bridges that were lined on both sides with houses. It has remained after all of those were replaced.

- Pont Des Arts: The Pont des Arts or Passerelle des Arts is a pedestrian bridge in Paris which crosses the River Seine. It links the Institut de France and the central square (cour carrée) of the Palais du Louvre, (which had been termed the "Palais des Arts" under the First French Empire).

Important Sites

2nd Arrondissment

Neighborhoods

Sentier

Important Buildings

- -- Bibliothèque nationale de France

- -- Paris Bourse

- -- Paris Opera

- -- Passage des Panoramas

- -- Galerie Vivienne

3rd Arrondissment

The 3rd arrondissement of Paris, situated on the right bank of the River Seine, is the smallest in area after the 2nd arrondissement. The arrondissement contains the northern, quieter part of the medieval district of Le Marais (while the 4th arrondissement contains Le Marais' more lively southern part, notably including the gay district of Paris). The oldest surviving private house of Paris, built in 1407, is to be found in the 3rd arrondissement, along the rue de Montmorency.

The ancient Jewish quarter, the Pletze (Little place in Yiddish) which dates from the 13th century begins in the eastern part of the 3rd arrondissement and extends into the 4th. It is home to the Musée d'art et d'histoire du judaïsme and the Agoudas Hakehilos synagogue designed by the architect Guimard. There are landmark stores selling traditional Jewish foods.

A small but slowly expanding Chinatown inhabited by immigrants from Wenzhou centers on the rue au Maire, near the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers housed in the medieval priory of Saint-Martin-des-Champs.

4th Arrondissment

The 4th arrondissement of Paris is also known as "arrondissement de l'Hôtel-de-Ville".

Situated on the Right Bank of the River Seine, it is bordered to the west by the 1st arrondissement; to the north by the 3rd, to the east by the 11th and 12th, and to the south by the Seine and the 5th.

The 4th arrondissement contains the Renaissance-era Paris City Hall. It also contains the Renaissance square of Place des Vosges, the overtly modern Pompidou Centre and the lively southern part of the medieval district of Le Marais,(while the more quiet northern part of Le Marais is contained inside the 3rd arrondissement). The eastern parts of the Île de la Cité (including Notre-Dame de Paris) as well as the Île Saint-Louis are also included within the 4th arrondissement.

The 4th arrondissement is known for its little streets, cafés, and shops but is often regarded by Parisians as expensive and congested.

History

The Île de la Cité has been inhabited since the 1st century BC, when it was occupied by the Parisii tribe of the Gauls. The Right Bank was first settled in the early Middle Ages (exactly: In the 5th century). Since the end of the 19th century, le Marais has been populated by a significant Jewish population, the Rue des Rosiers being at the heart of its community, with a handful of kosher restaurants. Since the 1990s, gay culture has made an impact on the arrondissement, opening a number of bars and cafés in the area by the town hall.

Important Places

- -- Bazar de l'Hôtel de Ville department store

- -- Berthillon

- -- Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal

- -- Centre Georges Pompidou

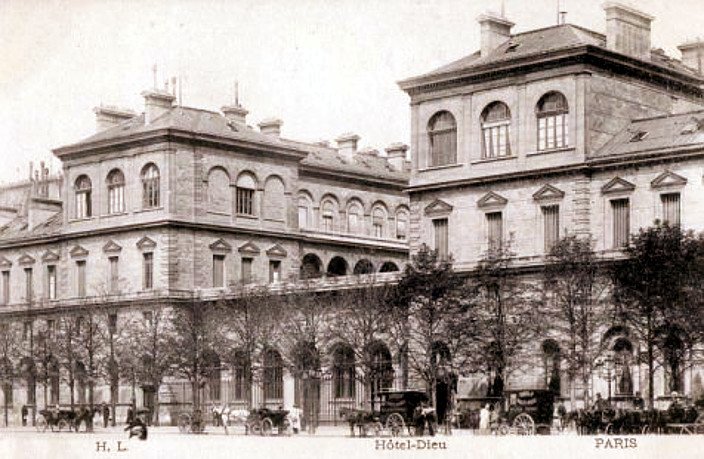

- -- Hôtel-Dieu hospital

- -- Hôtel de Sens

- -- Hôtel de Sully, on the site of a former orangery

- -- Hôtel de Ville, Paris

- -- Île Saint-Louis -- Home of the Chantry of Tremere in Paris.

- -- Le Marais

- -- Rue des Rosiers

- -- Lycée Charlemagne

- -- Maison européenne de la photographie

- -- Marché aux fleurs, Place Louis Lépine

- -- Musée Boleslas Biegas, Musée Adam Mickiewicz, and Salon Frédéric Chopin

- -- Musée de la Magie

- -- Notre-Dame de Paris

- -- Paris Morgue

- -- Pavillon de l'Arsenal

- -- Prefecture of Police

- -- Quai des Célestins (Paris)

- -- Saint-Jacques Tower

- -- St-Gervais-et-St-Protais Church

- -- Saint-Louis-en-l'Île Church

- -- Salle des Traditions de la Garde Républicaine

- -- Square du Temple, fortress and later prison

- -- Temple du Marais

5th Arrondissement

Introduction: Known as the Latin Quarter, this fabled neighborhood takes its name from the Sorbonne, where Latin was the common tongue for all students during the Middle Ages. The neighborhood has the feel of a small village and students mix freely with professionals in its winding streets. The rue Mouffetard is a primary artery where shops, international restaurants and student bars and cafés are found.

Situated on the left bank of the River Seine, it is one of the central arrondissements of the capital. The arrondissement is notable for being the location of the Quartier Latin, a district dominated by universities, colleges, and prestigious high schools.

The 5th arrondissement is also one of the oldest districts of the city, dating back to ancient times. Traces of the area's past survive in such sites as the Arènes de Lutèce, a Roman amphitheatre, and the Thermes de Cluny, a Roman thermae.The Eiffel Tower, the Musée d'Orsay, the Rodin Museum and the market street, Rue Cler can be found here. This very wealthy district is also known for being the home of foreign embassies and many international residents.

- -- Arnaud's Hôtel Particulier -- {La Dame: Carla Gagnon}

- -- Arènes de Lutèce -- The Arènes de Lutèce are among the most important remains from the Gallo-Roman era in Paris (known in antiquity as Lutetia, or Lutèce in French), together with the Thermes de Cluny. Lying in what is now the Latin Quarter, this amphitheater could once seat 15,000 people, and was used to present gladiatorial combats.

- -- Val de Grace Hospital --

- -- Pantheon, Paris --

- -- Ménagerie, le zoo du Jardin des Plantes --

- -- Musée national du Moyen Âge -- formerly Musée de Cluny (French pronunciation: [myze də klyni]), officially known as the Musée national du Moyen Âge – Thermes et hôtel de Cluny ("National Museum of the Middle Ages – Cluny thermal baths and mansion"), is a museum in Paris, France. It is located in the 5th arrondissement at 6 Place Paul-Painlevé, south of the Boulevard Saint-Germain, between the Boulevard Saint-Michel and the Rue Saint-Jacques.

- -- Latin Quarter of Paris -- The Latin Quarter of Paris (French: Quartier latin) is an area in the 5th and the 6th arrondissements of Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine, around the Sorbonne.

- -- Pierre and Marie Curie University -- (French: Université Pierre-et-Marie-Curie; abbreviated UPMC), also known as University of Paris VI, is a public research university and was established in 1971 following the division of the University of Paris (Sorbonne), and is a principal heir to Faculty of Sciences of the Sorbonne (French: Faculté des sciences de Paris), although it can trace its roots back to 1109 and the Abbey of St Victor. {Seigneur: Athanasios}

Holy Ground of the 5th Arrondissement

- -- Église de Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet -- {La Dame: Carla Gagnon}

- -- Église de Val de Grâce --

- -- Eglise de Saint Ephrem --

- -- Église de Saint-Étienne-du-Mont --

- -- Église Saint-Jacques-du-Haut-Pas --

- -- Église de Saint-Jean-l'Evangéliste --

6th Arrondissment

The 6th arrondissement includes world-famous educational institutions such as the École des Beaux-Arts de Paris and the Académie française, the seat of the French Senate as well as a concentration of some of Paris's most famous monuments such as Saint-Germain Abbey and square, St. Sulpice Church and square, the Pont des Arts and the Jardin du Luxembourg.

Situated on the left bank of the River Seine, this central arrondissement which includes the historic districts of Saint-Germain-des-Prés (surrounding the Abbey founded in the 6th century) and Luxembourg (surrounding the Palace and its Gardens) has played a major role throughout Paris history and is well known for its café culture and the revolutionary intellectualism (see: Existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir) and literature (see: Paul Éluard, Boris Vian, Albert Camus, Françoise Sagan) it has hosted.

With its world-famous cityscape, deeply rooted intellectual tradition, prestigious history, beautiful architecture and central location, the arrondissement has long been home to French intelligentsia. It is a major locale for art galleries and one of the most fashionable districts of Paris as well as Paris' most expensive area. The arrondissement is one of France's richest district in terms of average income, it is part of Paris Ouest alongside the 7th, 8th, 16th arrondissements and Neuilly, but has a much more bohemian and intellectual reputation than the others.

History

The current 6th arrondissement, dominated by the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés—founded in the 6th century—was the heart of the Catholic Church power in Paris for centuries, hosting many religious institutions.

In 1612, Queen Marie de Médicis bought an estate in the district and commissioned architect Salomon de Brosse to transform it into the outstanding Luxembourg Palace surrounded by extensive royal gardens. The new Palace turned the neighborhood into a fashionable district for French nobility.

Places of interest

- Académie française

- French Senate (Luxembourg Palace)

- Jardin du Luxembourg

- Medici Fountain

- Pont des Arts

- Pont Neuf

- Pont Saint-Michel

- Saint-Germain-des-Prés Quarter and former abbey

- Latin Quarter (partial)

- Saint-Sulpice church

- Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe

- Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier

- Café de Flore

- Les Deux Magots

- Polidor

- Hôtel de Chimay

- Hôtel Lutetia

- Café Procope

- Panthéon-Assas University Paris II

7th Arrondissment

The 7th arrondissement of Paris includes some of the major tourist attractions of Paris, such as the Eiffel Tower and the Hôtel des Invalides (Napoléon's resting place), and a concentration of such world-famous museums as the Musée d'Orsay, Musée Rodin, and the Musée du quai Branly.

Situated on the Rive Gauche—the "Left", or Southern, bank of the River Seine—this central arrondissement, which includes the historical aristocratic neighbourhood of Faubourg Saint-Germain, contains a number of French national institutions, among them the French National Assembly and numerous government ministries. It is also home to many foreign diplomatic embassies, some of them occupying outstanding Hôtels particuliers.

The arrondissement has been home to the French upper class since the 17th century, when it became the new residence of French highest nobility. The district has been so fashionable within the French aristocracy that the phrase le Faubourg—referring to the ancient name of the current 7th arrondissement—has been used to describe French nobility ever since. The 7th arrondissement of Paris and Neuilly-sur-Seine form the most affluent and prestigious residential area in France

History

During the 17th century, French high nobility started to move from the central Marais, the then-aristocratic district of Paris where nobles used to build their urban mansions[3] (see Hotel de Soubise), to the clearer, less populated and less polluted Faubourg Saint-Germain.

The district became so fashionable within the French aristocracy that the phrase le Faubourg has been used to describe French nobility ever since. The oldest and most prestigious families of the French nobility built outstanding residences in the area, such as the Hôtel Matignon, the Hôtel de Salm, and the Hôtel Biron.

After the Revolution many of these mansions, offering magnificent inner spaces, many receptions rooms and exquisite decoration, were confiscated and turned into national institutions. The French expression "les ors de la Republique" (literally "the golds of the Republic"), referring to the luxurious environment of the national palaces (outstanding official residences and priceless works of art), comes from that time.

During the Restauration, the Faubourg recovered its past glory as the most exclusive high nobility district of Paris and was the political heart of the country, home to the Ultra Party. After the Fall of Charles X, the district lost most of its political influence but remained the center of the French upper class' social life.

During the 19th century, the arrondissement hosted no less than five Universal Exhibitions (1855, 1867, 1878, 1889, 1900) that have immensely impacted its cityscape. The Eiffel Tower and the Orsay building have been built for these Exhibitions (respectively in 1889 and 1900).

8th Arrondissment

Situated on the right bank of the River Seine and centred on the Champs-Élysées, the 8th is, together with the 1st, 9th, 16th and 17th arrondissement, one of Paris's main business districts. It is also the location of many places of interest, among them the Champs-Élysées, the Arc de Triomphe and the Place de la Concorde, as well as the Élysée Palace, official residence of the President of France.

- Place de l'Étoile -- This is a large road junction in Paris, France, the meeting point of twelve straight avenues (hence its historic name, which translates as "Square of the Star") including the Champs-Élysées. Paris Axe historique ("historical axis") cuts through the Arc de Triomphe, which stands at the centre of the Place de l'Étoile.

9th Arrondissment

The 9th arrondissement (IXe arrondissement), located on the Right Bank, contains many places of cultural, historical and architectural interest, including the Palais Garnier, home to the Paris Opera, Boulevard Haussmann and its large department stores Galeries Lafayette and Printemps. Along with the 2nd and 8th arrondissements, it hosts one of the business centers of Paris, located around the Opéra.

10th Arrondissment

Situated on the right bank of the River Seine, the arrondissement contains two of Paris's six main railway stations: the Gare du Nord and the Gare de l'Est. Built during the 19th century, these two termini are among the busiest in Europe.

The 10th arrondissement also contains a large portion of the Canal Saint-Martin, linking the northeastern parts of Paris with the River Seine.

11th Arrondissment

Situated on the Right Bank of the River Seine, the 11th is one of the most densely populated urban districts not just of Paris, but of any European city.

Places of interest

12th Arrondissment

The 12th arrondissement of Paris (also known as "arrondissement de Reuilly") is situated on the right bank of the River Seine, the district has been significantly reorganized in recent decades, especially in the areas of Cour Saint-Émilion and Bercy, which now contain the French Ministry of Finances and the Bercy arena.

The 12th arrondissement contains the Opéra de la Bastille, the second largest opera house in Paris.

Places of interest

- Place de la Bastille (shared by the 4th, 11th and 12th arrondissements)

- Bois de Vincennes

- Jardin du Bassin de l'Arsenal

- Cimetière de Picpus

- Musée des Arts Forains

- Palais de la Porte Dorée (Cité nationale de l'histoire de l'immigration)

- Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy

- Parc de Bercy

- Paris Zoological Park (also known as Zoo de Vincennes)

- Promenade plantée

- Viaduc des arts

- Cirque de Ianua, 1900

13th Arrondissement: Place De I'talie

Introduction: A multi-cultural residential neighborhood which includes Paris' Chinatown and the ultra-modern Bibliothèque François Mitterand. The modernist Place d’Italie is the site of one of the most ambitious French urban renewal projects and the Butte aux Cailles neighborhood with its cobblestone streets and numerous restaurants, cafes and nightlife, preserves a village-like atmosphere within Paris.

Places of Interest

- -- Quartier Asiatique (Asian Quarter) -- also called Triangle de Choisy or Petite Asie, is the largest commercial and cultural center for the Asian community of Paris. It is located in the southeast of the 13th arrondissement in an area that contains many high-rise apartment buildings. Despite its status as a "Chinatown", the neighborhood also contains significant Vietnamese, Laotian and Cambodian populations.

- -- Maison de Tolbiac -- Rundown theater

- -- Bibliothèque nationale de France

- -- Paris Diderot University

- -- Paris Rive Gauche

- -- Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital

- -- Butte-aux-Cailles -- Quail Hill (neighborhood)

- -- Gare d'Austerlitz -- Austerlitz Station is one of the six large terminus railway stations in Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine in the southeastern part of the city, in the 13th arrondissement. It is the start of the Paris–Bordeaux railway; the line to Toulouse is connected to this line. Since the introduction of the TGV Atlantique — using Gare Montparnasse — Austerlitz has lost most of its long-distance southwestern services. It is used by some 30 million passengers annually, about half the number passing through Montparnasse.

- -- Gobelins Manufactory -- is a tapestry factory, which still gives tours three times a week. The factory belonged to the Gobelins family, and their name hangs on many things in the area, including the main road.

- -- Art Ludique -- Museum

- -- University of Chicago Center in Paris

- -- 6 Villa des Gobelins - residence of Hồ Chí Minh from July 1919 to July 19

- -- Cafe des Gobelins - Place where Ron Stewart comes

- -- Cafe Ca Ngam -

Hospitals

Streets and Squares of Interest

14th Arrondissement: Montparnasse

[[]]

Introduction: Montparnasse and the Cité Universitaire are found in this residential district traditionally known for its lively cafés and restaurants around the Boulevard Montparnasse.

- -- L'Ossuaire Municipal de Paris

- -- Cimetiery du Montparnasse

- -- Cimetière de Montrouge

- -- Fondation Cartier pour l'Art Contemporain

- -- Gare Montparnasse

- -- Paris Observatory

- -- La Sante Prison

15th Arrondissement: Parc De Exposition

[[]]

Introduction: This large primarily residential neighborhood ranges from very upscale in the area bordering the 7th arrondissement and the Seine, to relatively safe and affordable in the more outlying areas.

History

The loi du 16 juin 1859 decreed the annexation to Paris of the area between the old Wall of the Farmers-General and the wall of Thiers. The communes of Grenelle, Vaugirard, and Javel were incorporated into Paris in 1860.

Quarters

As in all the Parisian arrondissements, the fifteenth is made up of four administrative quarters (quartiers). The four administrative quarters of the 15th arrondissement.

- To the south, quartier Saint-Lambert occupies the former site of the village of Vaugirard, built along an ancient Roman road. The geography of the area was particularly suited to wine-making, as well as quarrying. In fact, many Parisian monuments, such as the École Militaire, were built from Vaugirard stone. The village, not yet being part of Paris, was considered by Parisians to be an agreeable suburb, pleasant for country walks or its cabarets and puppet shows. In 1860 Vaugirard was annexed to Paris, along with adjoining villages. Today, notable attractions in this area include the Parc des Expositions (an exhibition center which hosts the Foire de Paris, agricultural expositions, and car shows), and Parc Georges-Brassens, a park built on the former site of a slaughterhouse where every year wine by the name of Clos des Morillons is produced and auctioned at the civic center.

- To the east, quartier Necker was originally an uninhabited space between Paris and Vaugirard. The most well-known landmarks in the area are the Gare Montparnasse train station and the looming Tour Montparnasse office tower. The area around the train station has been renovated and now contains a number of office and apartment blocks, a park (the Jardin Atlantique, built directly over the train tracks), and a shopping center. Finally, the quartier contains a number of public buildings: the Lycée Buffon, the Necker Children's Hospital, as well as the private foundation Pasteur Institute.

- To the north, quartier Grenelle was originally a village of the same name. Grenelle plain extended from the current Hôtel des Invalides to the suburb of Issy-les-Moulineaux on the other side of the Seine, but remained mostly uninhabited in centuries past due to difficulties farming the land. At the beginning of the 19th century, an entrepreneur by the name of Violet divided off a section of the plain: this became the village of Beaugrenelle, known for its series of straight streets and blocks, which remain today. The whole area broke off from the commune of Vaugirard in 1830, becoming the commune of Grenelle, which was in turn annexed to Paris in 1860. A century later, a number of apartment and office towers were built along the Seine, the Front de Seine along with the Beaugrenelle shopping mall.

- To the west, quartier Javel lies to the south of Grenelle plain. In years past, it was the industrial area of the arrondissement: first with chemical companies (the famous Eau de Javel [bleach] was invented and produced there), then electrical companies (Thomson), and finally car manufacturers (Citroën), whose factories occupied a large part of the quartier up until the early 1970s. The industrial areas have since been rehabilitated, and the neighbourhood now contains Parc André Citroën, Georges Pompidou European Hospital, and a number of large office buildings and television studios (Sagem, Snecma, the Direction Générale de l'Aviation Civile, Canal Plus, France Télévisions, etc.). In addition, to the south of the circular highway (boulevard périphérique), an extension of the 15th, formerly an aerodrome at the beginning of the 20th century, is now a heliport, a gym and a recreation center.

16th Arrondissement: Trocadero

[[]]

Introduction: Although it is not as exclusive as the 7th arrondissement, the 16th is widely regarded as the neighborhood for the wealthy. The areas around rue de Passy and Place Victor Hugo offer upscale shopping and the Place de Trocadéro offers a splendid view of the Eiffel Tower from its trendy cafes.

The 16th arrondissement of Paris is also known as "Arrondissement de Passy"). It includes a concentration of museums between the Place du Trocadéro and the Place d'Iéna.

With its ornate 19th century buildings, large avenues, prestigious schools, museums and various parks, the arrondissement has long been known as one of French high society's favourite places of residence (comparable to London's Kensington and Chelsea)[2] to such an extent that the phrase "le 16e" (French pronunciation: [lə sɛzjɛm]) has been associated with great wealth in French popular culture. Indeed, the 16th arrondissement of Paris is France's third richest district for average household income, following the 7th, and Neuilly-sur-Seine;[3] They form the most affluent and prestigious residential area in France.

The 16th arrondissement hosts several large sporting venues, including: the Parc des Princes, which is the stadium where Paris Saint-Germain football club plays its home matches; Roland Garros Stadium, where the French Open tennis championships are held; and Stade Jean-Bouin, home to the Stade Français rugby union club. The Bois de Boulogne, the second-largest public park in Paris (behind only the Bois de Vincennes), is also located in this arrondissement.

Saint Just can be found here, he holds domain here.

- -- Rue de Pompe Metro

- -- Place de l'Étoile -- This is a large road junction in Paris, France, the meeting point of twelve straight avenues (hence its historic name, which translates as "Square of the Star") including the Champs-Élysées. Paris Axe historique ("historical axis") cuts through the Arc de Triomphe, which stands at the centre of the Place de l'Étoile.

- -- Passy -- Passy is an area of Paris, France, located in the 16th arrondissement, on the Right Bank. It is traditionally home to many of the city's wealthiest residents.

- -- Parc des Princes --

- -- Place des États-Unis --

17th Arrondissement: Palais De Congres

[[]]

Introduction: This diverse district really contains more than one neighborhood, with the portion, in the West, near the Arc de Triomphe and Parc Monceau, being very upscale.

- -- Place de l'Étoile -- This is a large road junction in Paris, France, the meeting point of twelve straight avenues (hence its historic name, which translates as "Square of the Star") including the Champs-Élysées. Paris Axe historique ("historical axis") cuts through the Arc de Triomphe, which stands at the centre of the Place de l'Étoile.

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

18th Arrondissement: Montmartre / Pigalle / Goutte d'Or / Quartier de La Chapelle

[[]]

Introduction: The 18th arrondissement, located on the Rive Droite (Right Bank), is one of the 20 Arrondissements of Paris, France. It is mostly known for hosting the district of Montmartre, which contains a hill dominated by the Sacré Cœur basilica, along with the house of music diva Dalida and well known Moulin Rouge cabaret.

The 18th arrondissement also contains the African and North African district of Goutte d'Or which is famous for its market, the marché Barbès, where one can find various products from that continent.

Districts within the 18th Arrondissement

- -- Montmartre --

- -- Pigalle --

- -- Goutte d'Or --

- -- Quartier de La Chapelle --

Places of Interest

- -- Basilique du Sacré-Cœur --

- -- Basilica of Sainte-Jeanne-d'Arc --

- -- Église Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre --

- -- Église Saint-Bernard de la Chapelle --

- -- Moulin Rouge --

- -- Musée d'Art Naïf - Max Fourny --

- The Serbian Orthodox Diocese of France and Western Europe has its headquarters in the arrondissement.

19th Arrondissement: Parc De La Villete

Introduction: Situated on the Right Bank of the River Seine, it is crossed by two canals, the Canal Saint-Denis and the Canal de l'Ourcq, which meet near the Parc de la Villette. The 19th arrondissement includes two public parks: the Parc des Buttes Chaumont, located on a hill, and the Parc de la Villette, which is home to both the Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie, a museum and exhibition centre, and the Conservatoire de Paris, one of the most renowned music schools in Europe and part of the Cité de la Musique.The Parc des Buttes Chaumont. A residential neighborhood with many ethnic restaurants and shops. Parc de la Villette is located here with its Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie museum and cultural center.

In the World of Darkness things have taken a decided turn for the worst here. The police have decided only major fires and or riots are worth showing up for here. What police do work here are under the thumb of several Anarchs that live in the area. It is not unheard of for deaths to happen here, and never be reported. Unlike other areas of Paris, people are slowly leaving the 19th. Many empty buildings and shop fronts mark it's streets.

There are several underground clubs here, and one Settite Temple. It is also common to find the Dark Freedom pack here, looking to recruit or hunt Anarchs...depending on which one amuses them more each night.

- -- :Parc des Buttes Chaumont

- -- :Parc de la Villette

- -- :Parc de la Butte-du-Chapeau-Rouge

- -- :The Cent Quatre arts centre

- -- :Psalm 69

- -- :Belleville, Paris

- -- :Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie

- -- :

- -- :

- -- :

20th Arrondissement: Belleville, Lachaise

The 20th arrondissement (also known as "arrondissement de Ménilmontant"), located on the Right Bank, is one of the 20 arrondissements of Paris, France. It contains the cosmopolitan districts of Ménilmontant and Belleville which have welcomed many successive waves of immigration since the mid-nineteenth century.

- -- Charonne quarter

- -- Belleville, Paris

- -- Ménilmontant

- -- The Père Lachaise Cemetery

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

History

Prehistory

In 2008, archaeologists of the Institut national de recherches archéologiques préventives (INRAP) (administered by France's Ministry of Higher Education and Research) digging at n° 62 Rue Henri-Farman in the 15th arrondissement, not far from the Left Bank of the Seine, discovered the oldest human remains and traces of a hunter-gatherer settlement in Paris, dating to about 8000 BC, during the Mesolithic period.

Other more recent traces of temporary settlements had been found at Bercy in 1991, dating from around 4500–4200 BC.[4] The excavations at Bercy found the fragments of three wooden canoes used by fishermen on the Seine, the oldest dating to 4800-4300 BC. They are now on display at the Carnavalet Museum. Excavations at the Rue Henri-Farman site found traces of settlements from the middle Neolithic period (4200-3500 BC); the early Bronze Age (3500-1500 BC); and the first Iron Age (800-500 BC). The archaeologists found ceramics, animal bone fragments, and pieces of polished axes. Hatchets made in eastern Europe were found at the Neolithic site in Bercy, showing that first Parisians were already trading with settlements in other parts of Europe.

The Parisii and Roman Conquest

Between 250 and 225 BC, during the Iron Age, the Parisii, a sub-tribe of the Celtic Senones, settled on the Île de la Cité and on the banks of the Seine. At the beginning of the 2nd century BC, they built an oppidum, a walled fort, either on the Île de la Cité or nearby (no trace of it has ever been found), and they built the first bridges over the Seine. The settlement was called "Lucotocia" (according to the ancient Greek geographer Strabo) or "Leucotecia" (according to Roman geographer Ptolemy), and may have taken its name from the Celtic word lugo or luco, for a marsh or swamp. It was the easiest place to cross the Seine, and it had a strategic position on the main trade route, via the Seine and Rhône rivers, between Britain and to the Roman colony of Provence and the Mediterranean Sea. The location and the fees for crossing the bridge and passing along the river made the new town prosperous, so much so that it was able to mint its own gold coins, which were used for trade across Europe. Coins from the towns along the Rhine and Danube and even from Cádiz in Spain were found in the excavations of the ancient city.

Julius Caesar and his Roman army campaigned in Gaul between 58 and 53 BC under the pretext of protecting the territory from Germanic invaders, but in reality to conquer it and annex it to the Roman Republic. In the summer of 53 BC, he visited the city and addressed the delegates of the Gallic tribes assembled before the temple on the Île de la Cité to ask them to contribute soldiers and money to his campaign. Wary of the Romans, the Parisii listened politely to Caesar, offered to provide some cavalry, but formed a secret alliance with the other Gallic tribes, under the leadership of Vercingetorix, and launched an uprising against the Romans in January 52 BC.

Caesar responded quickly. He force-marched six legions north to Orléans, where the rebellion had begun, and then to Gergovia, the home of Vercingetorix. At the same time, he sent his deputy Titus Labienus with four legions to subdue the Parisii and their allies, the Senons. The Commander of the Parisii, Camulogene, burned the bridge that connected the oppidum to the left bank of the Seine, so the Romans were unable to approach the town. Then Labienus and the Romans went downstream, built their own pontoon bridge at Melun and approached Lutetia on the right bank. Camulogene responded by burning the bridge to the right bank and burning the town on the Île de la Cité, before retreating to the left bank and making camp at what is now Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Labienus deceived the Parisii with a clever ruse; in the middle of the night, he sent part of his army, making as much noise as possible, upstream to Melun, left his most inexperienced soldiers in their camp on the right bank, and, with his best soldiers, quietly crossed the Seine to the left bank and laid a trap for the Parisii. Camulogene, believing that the Romans were retreating, divided his own forces, some to capture the Roman camp, which he thought was abandoned, and others to pursue the Roman army. Instead, he ran directly into the best two Roman legions on the plain of Grenelle, near the site of the modern Eiffel Tower and the École Militaire. The Parisii fought bravely and desperately in what became known as the Battle of Lutetia; Camulogene was killed and his soldiers were cut down by the disciplined Romans. Despite the defeat, the Parisii continued to resist the Romans; they sent eight thousand men to fight with Vercingetorix in his last stand against the Romans at the Battle of Alesia.

Roman Lutetia

The Romans built an entirely new city as a base for their soldiers and the Gallic auxiliaries intended to keep an eye on the rebellious province. The new city was called Lutetia (Lutèce) or "Lutetia Parisiorum" ("Lutèce of the Parisii"). The name probably came from the Latin word luta, meaning mud or swamp Caesar had described the great marsh, or marais, along the right bank of the Seine. The major part of the city was on the left bank of the Seine, which was higher and less prone to flood. It was laid out following the traditional Roman town design along a north-south axis (known in Latin as the cardo maximus). On the left bank, the main Roman street followed the route of the modern day Rue Saint-Jacques. It crossed the Seine and traversed the Île de la Cité on two wooden bridges: the "Petit Pont" and the "Grand Pont" (today's Pont Notre-Dame). The port of the city, where the boats docked, was located on the island where the parvis of Notre Dame is today. On the right bank, it followed the modern Rue Saint-Martin. On the left bank, the cardo was crossed by a less-important east-west decumanus, today's Rue Cujas, Rue Soufflot and Rue des Écoles.

The city was centered on the forum atop the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève between the Boulevard Saint-Michel and the Rue Saint-Jacques, where the Rue Soufflot is now located. The main building of the forum was one hundred meters long and contained a temple, a basilica used for civic functions and a square portico which covered shops. Nearby, on the slope of the hill, was an enormous amphitheatre built in the 1st century AD, which could seat ten to fifteen thousand spectators, though the population of the city was only six to eight thousand. Fresh drinking water was supplied to the city by an aqueduct sixteen kilometres long from the basin of Rungis and Wissous. The aqueduct also supplied water to the famous baths, or Thermes de Cluny, built near the forum at the end of the 2nd century or beginning of the 3rd century. Under Roman rule, the town was thoroughly Romanised and grew considerably.

Besides the Roman architecture and city design, the newcomers imported Roman cuisine: modern excavations have found amphorae of Italian wine and olive oil, shellfish, and a popular Roman sauce called garum. Despite its commercial importance, Lutetia was only a medium-sized Roman city, considerably smaller than Lugdunum (Lyon) or Agedincum (Sens), which was the capital of the Roman province of Lugdunensis Quarta, in which Lutetia was located.

Christianity was introduced into Paris in the middle of the 3rd century AD. According to tradition, it was brought by Saint Denis, the Bishop of the Parisii, who, along with two others, Rustique and Éleuthère, was arrested by the Roman prefect Fescennius. When he refused to renounce his faith, he was beheaded on Mount Mercury. According to the tradition, Saint Denis picked up his head and carried it to a secret Christian cemetery of Vicus Cattulliacus about six miles away. A different version of the legend says that a devout Christian woman, Catula, came at night to the site of the execution and took his remains to the cemetery. The hill where he was executed, Mount Mercury, later became the Mountain of Martyrs ("Mons Martyrum"), eventually Montmartre. A church was built on the site of the grave of St. Denis, which later became the Basilica of Saint-Denis. By the 4th century, the city had its first recognized bishop, Victorinus (346 AD). By 392 AD, it had a cathedral.

Late in the 3rd century AD, the invasion of Germanic tribes, beginning with the Alamans in 275 AD, caused many of the residents of the Left Bank to leave that part of the city and move to the safety of the Île de la Cité. Many of the monuments on the Left Bank were abandoned, and the stones used to build a wall around the Île de la Cité, the first city wall of Paris. A new basilica and baths were built on the island; their ruins were found beneath the square in front of the cathedral of Notre Dame. Beginning in 305 AD, the name Lutetia was replaced on milestones by Civitas Parisiorum, or "City of the Parisii". By the period of the Late Roman Empire (the 3rd-5th centuries AD), it was known simply as "Parisius" in Latin and "Paris" in French.

From 355 until 360, Paris was ruled by Julian, the nephew of Constantine the Great and the Caesar, or governor, of the western Roman provinces. When he was not campaigning with the army, he spent the winters of 357-358 and 358-359 in the city living in a palace on the site of the modern Palais de Justice, where he spent his time writing and establishing his reputation as a philosopher. In February 360, his soldiers proclaimed him Augustus, or Emperor, and for a brief time, Paris was the capital of the western Roman Empire, until he left in 363 and died fighting the Persians. Two other emperors spent winters in the city near the end of the Roman Empire while trying to halt the tide of Barbarian invasions: Valentinian I (365-367) and Gratian in 383 AD.

The gradual collapse of the Roman empire due to the increasing Germanic invasions of the 5th century, sent the city into a period of decline. In 451 AD, the city was threatened by the army of Attila the Hun, which had pillaged Treves, Metz and Reims. The Parisians were planning to abandon the city, but they were persuaded to resist by Saint Geneviève (422-502). Attila bypassed Paris and attacked Orléans. In 461, the city was threatened again by the Salian Franks led by Childeric I (436-481). The siege of the city lasted ten years. Once again, Geneviève organized the defense. She rescued the city by bringing wheat to the hungry city from Brie and Champagne on a flotilla of eleven barges. She became the patron saint of Paris shortly after her death.

In 481, the son of Childeric, Clovis I, just sixteen years old, became the new ruler of the Franks. In 486, he defeated the last Roman armies, and became the ruler of all of Gaul north of the Loire River. With the consent of Geneviève, he entered Paris. He was converted to Christianity by his wife Clotilde, was baptised at Reims in 496 and made Paris his capital in 508

See: Lutetia -- The Gallo-Roman city of Lutetia (also Lutetia Parisiorum in Latin, in French Lutèce) was the predecessor of present-day Paris.

From Clovis to the Capetian Kings

Clovis I and his successors of the Merovingian dynasty built a host of religious edifices in Paris: a basilica on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, near the site of the ancient Roman Forum; the cathedral of Saint-Étienne, where Notre Dame now stands; and several important monasteries, including one in the fields of the Left Bank that later became the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. They also built the Basilica of Saint-Denis, which became the necropolis of the kings of France. None of the Merovingian buildings survived, but there are four marble Merovingian columns in the church of Saint-Pierre de Montmartre. The kings of the Merovingian dynasty were buried in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des Prés, however Dagobert I, the last king of the Merovingian dynasty, who died in 639, was the first Frankish king to be buried in the Basilica of Saint-Denis.

The kings of the Carolingian dynasty, who came to power in 751, moved the Frankish capital to Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) and paid little attention to Paris, though King Pepin the Short did build an impressive new sanctuary at Saint-Denis, which was consecrated in the presence of Charlemagne on 24 February 775.

In the 9th century, the city was repeatedly attacked by the Vikings, who sailed up the Seine on great fleets of Viking ships. They demanded a ransom and ravaged the fields. In 857, Björn Ironside almost destroyed the city. In 885-886, they laid a one-year siege to Paris and tried again in 887 and in 889, but were unable to conquer the city, as it was protected by the Seine and the walls of the Île de la Cité. The two bridges, vital to the city, were additionally protected by two massive stone fortresses, the Grand Châtelet on the Right Bank and the "Petit Châtelet" on the Left Bank, built on the initiative of Joscelin, the bishop of Paris. The Grand Châtelet gave its name to the modern Place du Châtelet on the same site.

At the end of the 10th century, a new dynasty of kings, the Capetians, founded by Hugh Capet in 987, came to power. Though they spent little time in the city, they restored the royal palace on the Île de la Cité and built a church where the Sainte-Chapelle stands today. Prosperity returned gradually to the city and the Right Bank began to be populated. On the Left Bank, the Capetians founded an important monastery: the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Its church was rebuilt in the 11th century. The monastery owed its fame to its scholarship and illuminated manuscripts.

The Middle Ages

At the beginning of the 12th century, the French kings of the Capetian dynasty controlled little more than Paris and the surrounding region, but they did their best to build up Paris as the political, economic, religious and cultural capital of France. The distinctive character of the city's districts continued to emerge at this time. The Île de la Cité was the site of the royal palace, and construction of the new Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris began in 1163. The Left Bank (south of the Seine) was the site of the new University of Paris established by the Church and royal court to train scholars in theology, mathematics and law, and the two great monasteries of Paris: the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés and the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. The Right Bank (north of the Seine) became the center of commerce and finance, where the port, the central market, workshops and the houses of merchants were located. A league of merchants, the Hanse parisienne, was established and quickly became a powerful force in the city's affairs.

The Royal Palace and the Louve

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, the royal residence was on the Île de la Cité. Between 1190 and 1202, King Philip II built the massive fortress of the Louvre, which was designed to protect the Right Bank against an English attack from Normandy. The fortified castle was a great rectangle of 72 by 78 meters, with four towers, and surrounded by a moat. In the center was a circular tower thirty meters high. The foundations can be seen today in the basement of the Louvre Museum.

Before he departed for the Third Crusade, Philip II began construction of new fortifications for the city. He built a stone wall on the Left Bank, with thirty round towers. On the Right Bank, the wall extended for 2.8 kilometers, with forty towers to protect the new neighborhoods of the growing medieval city. Many pieces of the wall can still be seen today, particularly in the Le Marais district. His third great project, much appreciated by the Parisians, was to pave the foul-smelling mud streets with stone. Over the Seine, he also rebuilt two wooden bridges in stone, the Petit-Pont and Grand-Pont, and he began construction on the Right Bank of a covered market, Les Halles.

King Philip IV (r. 1285-1314) reconstructed the royal residence on the Île de la Cité, transforming it into a palace. Two of the great ceremonial halls still remain within the structure of the Palais de Justice. He also built a more sinister structure, the Gibbet of Montfaucon, near the modern Place du Colonel Fabien and the Parc des Buttes Chaumont, where the corpses of executed criminals were displayed. On 13 October 1307, he used his royal power to arrest the members of the Knights Templar, who, he felt, had grown too powerful, and on 18 March 1314, he had the Grand Master of the Order, Jacques de Molay, burned at the stake on the western point of the Île de la Cité.

Between 1356 and 1383, king Charles V built a new wall of fortifications around the city: an important portion of this wall discovered during archaeological diggings in 1991-1992 can be seen within the Louvre complex, under the Place du Carrousel. He also built the Bastille, a large fortress guarding the Porte Saint-Antoine at the eastern end of Paris, and an imposing new fortress at Vincennes, east of city. Charles V moved his official residence from the Île de la Cité to the Louvre, but preferred to live in the Hôtel Saint-Pol, his beloved residence.

Grand Cathedrals and the Gothic Style

The flourishing of religious architecture in Paris was largely the work of Suger, the abbot of Saint-Denis from 1122-1151 and an advisor to Kings Louis VI and Louis VII. He rebuilt the facade of the old Carolingian Basilica of Saint Denis, dividing it into three horizontal levels and three vertical sections to symbolize the Holy Trinity. Then, from 1140 to 1144, he rebuilt the rear of the church with a majestic and dramatic wall of stained glass windows that flooded the church with light. This style, which later was named Gothic, was copied by other Paris churches: the Priory of Saint-Martin-des-Champs, Saint-Pierre de Montmartre, and Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and quickly spread to England and Germany.

An even more ambitious building project, a new cathedral for Paris, was begun by bishop Maurice de Sully in about 1160, and it continued for two centuries. The first stone of the choir of the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris was laid in 1163, and the altar was consecrated in 1182. The facade was built between 1200 and 1225, and the two towers were built between 1225 and 1250. It was an immense structure, 125 meters long, with towers 63 meters high and seats for 1300 worshipers. The plan of the cathedral was copied on a smaller scale on the Left Bank of the Seine in the church of Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre.

In the 13th century, King Louis IX (r. 1226–1270), known to history as "Saint Louis", built the Sainte-Chapelle, a masterpiece of Gothic architecture, especially to house relics from the crucifixion of Christ. Built between 1241 and 1248, it has the oldest stained glass windows preserved in Paris. At the same time that the Saint-Chapelle was built, the great stained glass rose windows, eighteen meters high, were added to the transept of the cathedral.

The University of Paris

Under Kings Louis VI and Louis VII, Paris became one of the principal centers of learning in Europe. Students, scholars and monks flocked to the city from England, Germany and Italy to engage in intellectual exchanges, to teach and be taught. They studied first in the different schools attached to Notre-Dame and the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The most famous teacher was Pierre Abelard (1079–1142), who taught five thousand students at the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. The University of Paris was originally organized in the mid-12th century as a guild or corporation of students and teachers. It was recognized by King Philip II in 1200 and officially recognized by Pope Innocent III, who had studied there, in 1215. Some twenty thousand students lived on the Left Bank, which became known as the Latin Quarter, because Latin was the language of instruction at the university and the common language in which the foreign students could converse. The poorer students lived in colleges (Collegia pauperum magistrorum), which were hotels where they were lodged and fed. In 1257, the chaplain of Louis IX, Robert de Sorbon, opened the oldest and most famous College of the University, which was later named after him, the Sorbonne. From the 13th to the 15th century, the University of Paris was the most important school of Roman Catholic theology in western Europe; its teachers included Roger Bacon from England, Saint Thomas Aquinas from Italy, and Saint Bonaventure from Germany.

The Merchants of Paris

Beginning in the 11th century, Paris had been governed by a Royal Provost, appointed by the king, who lived in the fortress of Grand Châtelet. Saint Louis created a new position, the Provost of the Merchants (prévôt des marchands), to share authority with the Royal Provost and recognize the growing power and wealth of the merchants of Paris. The importance of guilds of craftsmen was reflected in the gesture of the city government to adapt its coat of arms, featuring a ship, from the symbol of the guild of the boatmen. Saint Louis created the first municipal council of Paris, with twenty-four members.

In 1328, the population of the city was about 200,000, which made it the most populous city in Europe. With the growth in population came growing social tensions; the first riots took place in December 1306 against the Provost of the Merchants, who was accused of raising rents. The houses of many merchants were burned, and twenty-eight rioters were hanged. In January 1357, Étienne Marcel, the Provost of Paris, led a merchants' revolt using violence (such as the killing of the counselors of the dauphin before his very eyes) in a bid to curb the power of the monarchy and obtain privileges for the city and the Estates General, which had met for the first time in Paris in 1347. After initial concessions by the Crown, the city was retaken by royalist forces in 1358. Marcel was killed and his followers dispersed (a number of which were later put to death).

Plague and the Hundred Year's War

In the middle of the 14th century, Paris was struck by two great catastrophes: the Bubonic plague and the Hundred Years' War. In the first epidemic of the plague in 1348-1349, forty to fifty thousand Parisians died, a quarter of the population. The plague returned in 1360-61, 1363, and 1366-1368. During the 16th and 17th centuries, plague visited the city almost one year out of three.

The war was even more catastrophic. Beginning in 1346, the English army of King Edward III pillaged the countryside outside the walls of Paris. Ten years later, when King John II was captured by the English at the Battle of Poitiers, disbanded groups of mercenary soldiers looted and ravaged the surroundings of Paris.

More misfortunes followed. An English army and its allies from the Duchy of Burgundy invaded Paris during the night of 28–29 May 1418. Beginning in 1422, the north of France was ruled by the Duke of Bedford, the regent for the infant King Henry VI of England, who was resident in Paris while King Charles VII of France only ruled France south of the Loire River. During her unsuccessful attempt at taking Paris on 8 September 1429, Joan of Arc was wounded just outside the Porte Saint-Honoré, the westernmost fortified entrance of the Wall of Charles V, not far from the Louvre. On 16 December 1431, Henry VI of England, at the age of 10-year, was crowned King of France at Notre Dame cathedral. The English did not leave Paris until 1436, when Charles VII was finally able to return. Many areas of the capital of his kingdom were in ruins, and a hundred thousand of its inhabitants, half the population, had left the city.

When Paris was again the capital of France, the succeeding monarchs chose to live in the Loire Valley and visited Paris only on special occasions. King Francis I finally returned the royal residence to Paris in 1528.

Besides the Louvre, Notre-Dame and several churches, two large residences from the Middle Ages can still be seen in Paris: the Hôtel de Sens, built at the end of the 15th century as the residence of the Archbishop of Sens, and the Hôtel de Cluny, built in the years 1485–1510, which was the former residence of the abbot of the Cluny Monastery, but now houses the Museum of the Middle Ages. Both buildings were much modified in the centuries that followed. The oldest surviving house in Paris is the house of Nicolas Flamel built in 1407, which is located at 51 Rue de Montmorency. It was not a private home, but a hostel for the poor.

The 16th Century

By 1500, Paris had regained its former prosperity, and the population reached 250,000. Each new king of France added buildings, bridges and fountains to embellish his capital, most of them in the new Renaissance style imported from Italy.

King Louis XI rarely visited Paris, but he rebuilt the old wooden Pont Notre Dame, which had collapsed on 25 October 1499. The new bridge, opened in 1512, was made of dimension stone, paved with stone, and lined with sixty-eight houses and shops. On 15 July 1533, King Francis I laid the foundation stone for the first Hôtel de Ville, the city hall of Paris. It was designed by his favorite Italian architect, Domenico da Cortona, who also designed the Château de Chambord in the Loire Valley for the king. The Hôtel de Ville was not finished until 1628. Cortona also designed the first Renaissance church in Paris, the church of Saint-Eustache (1532) by covering a Gothic structure with flamboyant Renaissance detail and decoration. The first Renaissance house in Paris was the Hôtel Carnavalet, begun in 1545. It was modeled after the Grand Ferrare, a mansion in Fontainbleau designed by Italian architect Sebastiano Serlio. It is now the Carnavalet Museum.

In 1534, Francis I became the first French king to make the Louvre his residence; he demolished the massive central tower to create an open courtyard. Near the end of his reign, Francis decided to build a new wing with a Renaissance facade in place of one wing built by King Philip II. The new wing was designed by Pierre Lescot, and it became a model for other Renaissance facades in France. Francis also reinforced the position of Paris as a center of learning and scholarship. In 1500, there were seventy-five printing houses in Paris, second only to Venice, and later in the 16th century, Paris brought out more books than any other European city. In 1530, Francis created a new faculty at the University of Paris with the mission of teaching Hebrew, Greek and mathematics. It became the Collège de France.

Francis I died in 1547, and his son, Henry II, continued to decorate Paris in the French Renaissance style: the finest Renaissance fountain in the city, the Fontaine des Innocents, was built to celebrate Henry's official entrance into Paris in 1549. Henry II also added a new wing to the Louvre, the Pavillon du Roi, to the south along the Seine. The bedroom of the king was on the first floor of this new wing. He also built a magnificent hall for festivities and ceremonies, the Salle des Cariatides, in the Lescot Wing.

Henry II died 10 July 1559 from wounds suffered while jousting at his residence at the Hôtel des Tournelles. His widow, Catherine de Medicis, had the old residence demolished in 1563, and between 1564 and 1572 constructed a new royal residence, the Tuileries Palace perpendicular to the Seine, just outside the Charles V wall of the city. To the west of the palace, she created a large Italian-style garden, the Jardin des Tuileries.