Venice -- medieval

Il Proemio

Called "the Most Serene Commune of Venice" (or La Serenissima), Venice is the second-largest city in Italy, with upwards of 120,000 inhabitants. It is also a hotbed of Cainite intrigue. Catholic Lasombra struggle with their heretical brethren, and the bustling port brings Cainites from across the Mediterranean, all under the watchful eyes of Narses, Prince of Venice and Archbishop of Nod. Therefore, Venice is in the unique position of being a crossroads used by Cainite and kine alike. It is a neutral meeting ground where East meets West and anything can be purchased for a price. Those new to the city may find Venice unsettling, even disturbing.

Quotazione

- "E lì a Venezia ha dato"

- "Il suo corpo nella terra di quel piacevole paese,"

- "E la sua pura anima al suo capitano Cristo,"

- "Sotto i cui colori aveva combattuto così a lungo."

- {"And there at Venice gave"}

- {"His body to that pleasant country's earth,"}

- {"And his pure soul unto his captain Christ,"}

- {"Under whose colours he had fought so long."}

- -- Act IV, scene 1, line 97, Richard II (c. 1595).

Aspetto

Clima

Venice has a Humid subtropical climate, with cool winters and very warm summers. Precipitation is spread relatively evenly throughout the year, and averages 29.4 in.

Dispositivo di Città

Economia

Preface

Venice, situated at the far end of the Adriatic Sea, gained large scale profit of the adjacent middle European markets (Eastern European). So did the fact that the town belonged to the Byzantine Empire. Along with increasing autonomy it gained far reaching privileges in both Empires. As a consequence of the Fourth Crusade, the venetian doge became - at least nominally - dominator of three-eighths of Byzantium, all trading ways opened up and a colonial empire, concentrated on the Aegean, developed.

As a consumer center Venice did play a rather meaningless role. But within a long process of adaptation and learning the Venetians developed techniques of trade, forms of companies and methods of finance, but to the same degree means of business development, of insurance and patent protection, in addition technical and organizational innovations, last not least means of controlling the money-market, that made them forerunners of developments for the rest of Europe.

Nevertheless only the nobility or patriciate had the right to exercise the wealth-bringing long-distance trade. It was the same patriciate that erected a monopoly of political leadership. It left production and small business to the strata of its society that were not capable of becoming a member of the council - which was the visible sign of nobility. On the other hand they provided protection against competitors, against violation of secrecy - and exercised strict control.

Ab initio Venice had to face fierce competition and rivalry, especially coming from Genoa. War, whether declared or not, was the normal status that for four times culminated in year-long open wars, conducted with all means. Finally, the tiny - as far as its expanse was concerned - super power had to draw back, because the world powers of those days, Spain and the Ottoman Empire, had a world of natural and human resources, Amsterdam, London and Lisbon the political and economic means that Venice could not afford in that ever growing range.

Introduction

Venice's historical roots reach at least as far back as the Etruscan Culture. The settlements from which later on Venice grew up, could revive the late Roman trade with Northern Italy. At the same time Venice succeeded in extending its privileges in the Byzantine Empire. Byzantium as well as the Holy Roman empire were always prepared to concede privileges to the Venetian traders, when they were in heavy political constraints. These far going privileges - as barbed as they were - formed the judicial basis for the preponderance of the Adriatic town in commercial matters. At the same time it reached its aims to overthrow the Dalmatian and Italian rivals and to secure the routes of transport.

The crusades brought intensification of trade, of which Venice took profit so that it soon ranked first among the trading nations. Already a century before the conquest of Constantinople (1204) lots of traders' colonies flourished. This the more, when the Venetians conquered Crete and other important points that together formed a colonial empire, the backbone of free trade and of the convoys of large ships sent to the markets around the Mediterranean sea. In addition it offered significant opportunities to regulate the local balances of power and secured partly the means of living - especially wheat - for the mother town.

Taking and keeping control of long distance trade from Venice necessitated new means and measures of checking and controlling. The "commercial revolution" with its new cultural, organizational forms, not to forget with its new ways of living, led to a never before seen predominance of economy, especially as the economically leading clans were at the same time incorporated in the vehicles of political power. Economic success attracted - as ever - thousands of people, amongst them many artisans with capabilities of utmost importance, such as the diversification of new artistic techniques and technical processes.

The Crusades and the conquest of the Byzantine capital opened a direct route to Middle-eastern and Asian markets. But these voyages, similar to the costly convoys to Flanders, Tunisia, Syria and Constantinople, required huge amounts of capital, which normally meant credit. This fact is closely combined with the early reduction of barter and a strong position of money-mediated trade. A long learning-process that lead to a rudimentary economic policy started, including patent protection, legal provisions for the opening of trade routes, and provisions to prevent the debasing of trade metals like gold.

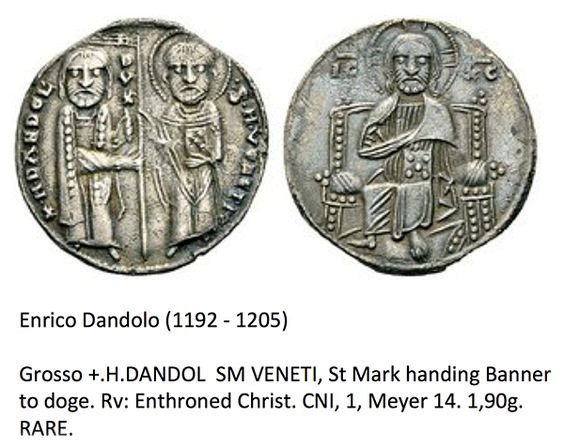

The city of Venice could finance its everyday duties via the revenues drawn from tariffs, but in difficult times it rigidly made recourse to the estate and capital of the thousand rich families. Money at its core in those days mostly consisted of gold or silver. As a consequence, the economy depended heavily on the timely increase and decrease of these metals. So Venice had to develop a highly flexible system of currencies and exchange rates between coins consisting of silver and gold, if it wanted to preserve and enhance its role as a platform and turntable of international transaction. In addition the exchange rates between the currencies circulating within and outside of Venice had to be adjusted adequately. On the other hand the nobility had hardly any scruples to force its colonies to accept exchange rates, which were only useful for the rich.

In addition Italian traders were used to means of payment, which could help avoid the transportation of gold and silver, that were particularly expensive and dangerous. Crediting became a way to bridge the ubiquitous lack of noble metals, and at the same time, to accelerate the turnover of goods, these techniques were a primitive form of banking and the creation of letters of credit, the forerunner of paper money. Also available and helpful were to float loans, used as a kind of traders' money, circulating from hand to hand. The moneychangers played as important a role as the later state-controlled banks whose predecessors in Venice were the "wheat chamber" or Camera frumenti.

Despite the predominance of intermediary trade, ship building was an industry of utmost importance right from the beginning - and it was by far the most important employer. Quite important in the later Middle Ages were the production of draperies, silk and glass. Still the salt monopoly was of utmost importance, even more so than the trade in wheat and millet. Indeed, the foundation of patrician wealth lay specifically with this particular trade and it contributed more to their coffers than did the rest of Venice's varied trades.

Geography

Sestiere

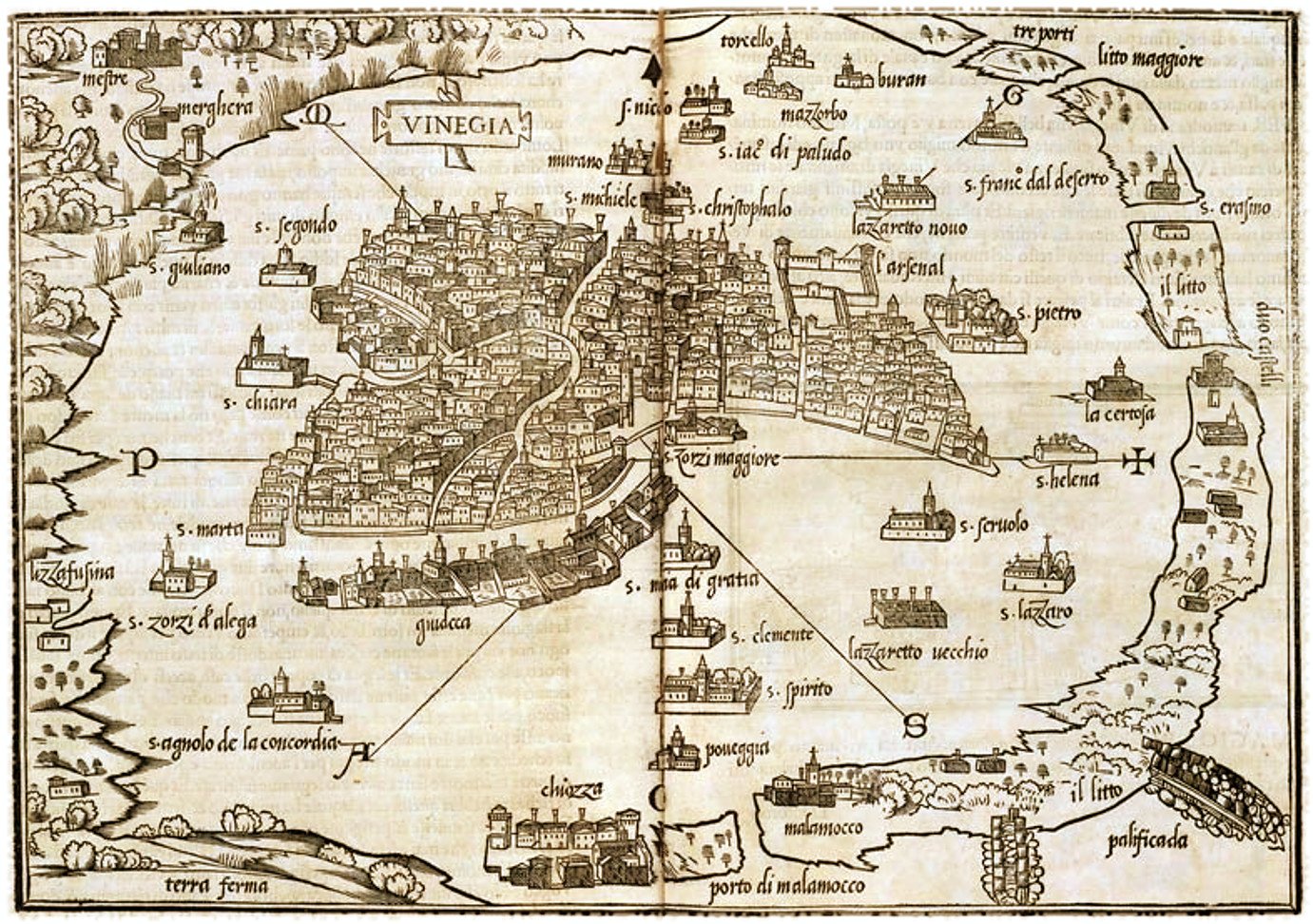

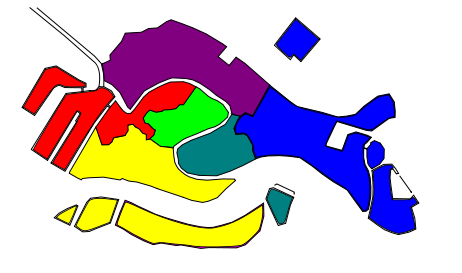

The whole pensolon (municipality) is divided into 6 boroughs. One of these (the historic city) is divided into six areas called sestieri: Cannaregio, San Polo, Dorsoduro (including the isla Giudecca and Sacca Fisola), Santa Croce, San Marco (including San Giorgio Maggiore) and Castello (including San Pietro di Castello and Sant'Elena). Each sestiere was administered by a procurator and his staff. The six fingers or phalanges of the ferro on the bow of a gondola represent the six sestieri.

The sestieri are divided into parishes – initially 70 in 1033. These parishes predate the sestieri, which were created in about 1170. Each parish exhibited unique characteristics but also belonged to an integrated network. The community chose its own patron saint, staged its own festivals, congregated around its own market center, constructed its own bell towers and developed its own customs.

Other islands of the Venetian Lagoon do not form part of any of the sestieri, having historically enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy.

,

,

- -- Cannaregio

- -- San Polo

- -- Dorsoduro

- -- Santa Croce

- -- San Marco

- -- Castello

Islands of the Venetian Lagoon

The largest islands of the archipelago

- Murano -- Island of salt mines and the guild of glass-makers, the majority of the islands inhabitants are fishermen or farmers. {Autonomous township}

- Sant'Erasmo -- A tributary of Murano, it boasts a well used port which doubles as a smuggler's haven, while the remainder of the island is largely agricultural.

- Chioggia

- Giudecca

- Mazzorbo

- Torcello

- Sant'Elena

- La Certosa

- Burano

- Tronchetto

- Sacca Fisola

- Isola di San Michele -- The traditional cemetery island, San Michele is also home to a major church, monastery and the infamous Casa Giovanni.

- Sacca Sessola

- Santa Cristina

Storia

Introduzione

The Republic of Venice (Venetian: Repùblica Vèneta; Italian: Repubblica di Venezia), traditionally known as the Most Serene Republic of Venice (Venetian: Serenìsima Repùblica Vèneta; Italian: Serenissima Repubblica di Venezia), was a sovereign state and maritime republic in northeastern Italy, which existed for a millennium between the 8th century and the 18th century. It was based in the lagoon communities of the historically prosperous city of Venice, and was a leading European economic and trading power during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Umili Origini

The history of the Republic of Venice traditionally begins with its foundation at noon on Friday 25 March AD 421, by authorities from Padua, to establish a trading-post in that region of northern Italy; the founding of the Venetian republic also was marked with the founding of the church of St. James. The early city of Venice existed as a collection of lagoon communities who united for mutual defense against the Lombards, as the power of the Byzantine Empire dwindled in northern Italy in the late 7th century.

Early in the 8th century, the people of the lagoon elected their first leader Orso Ipato (Ursus), who was confirmed by Byzantium with the titles of hypatus and dux. Historically, Ursus was the first Doge of Venice. Tradition, however, since the early 11th century, dictates that the Venetians first proclaimed one Paolo Lucio Anafesto (Anafestus Paulicius) duke in AD 697, although the tradition dates only from the chronicle of John, deacon of Venice (John the Deacon); nonetheless, the power base of the first doges was in Eraclea.

Il Sorgere

Orso Ipato's successor, Teodato Ipato, moved his seat from Eraclea to Malamocco in the 740s. He was the son of Orso and represented the attempt of his father to establish a dynasty. Such attempts were more than commonplace among the doges of the first few centuries of Venetian history, but all were ultimately unsuccessful. During the reign of Teodato Ipato, Venice became the only remaining Byzantine possession in Italy.

The changing politic of the Frankish Empire began to change the factional division of Venice. One faction was decidedly pro-Byzantine. They desired to remain well-connected to the Empire. Another faction, republican in nature, believed in continuing along a course towards practical independence. The other main faction was pro-Frankish. Supported mostly by clergy (in line with papal sympathies of the time), they looked towards the new Carolingian king of the Franks, Pepin the Short, as the best provider of defense against the Lombards. A minor, pro-Lombard, faction was opposed to close ties with any of these further-off powers and interested in maintaining peace with the neighboring Lombard kingdom, which surrounded Venice except on the seaward side.

Teodato Ipato was assassinated and his throne usurped, but the usurper, Galla Gaulo, who suffered a like fate within a year. During the reign of his successor, Domenico Monegario, Venice changed from a fisherman's town to a port of trade and center of merchants. Shipbuilding was also greatly advanced and the pathway to Venetian dominance of the Adriatic was laid. Also during Domenico Monegario's tenure, the first dual tribunal was instituted. Each year, two new tribunes were elected to oversee the doge and prevent abuse of power.

The pro-Lombard Monegario was succeeded in 764, by a pro-Byzantine Eraclean, Maurizio Galbaio. Galbaio's long reign (764-787) vaulted Venice forward to a place of prominence not just regionally but internationally and saw the most concerted effort yet to establish a dynasty. Maurizio oversaw the expansion of Venetia to the Rialto islands. He was succeeded by his equally long-reigning son, Giovanni. Giovanni clashed with Charlemagne over the slave trade and entered into a conflict with the Venetian church.

Dynastic ambitions were shattered when the pro-Frankish faction was able to seize power under Obelerio degli Antoneri in 804. Obelerio brought Venice into the orbit of the Carolingian Empire. However, by calling in Charlemagne's son Pepin, rex Langobardorum, to his defense, he raised the ire of the populace against himself and his family and they were forced to flee during Pepin's siege of Venice. The siege proved a costly Carolingian failure. It lasted six months, with Pepin's army ravaged by the diseases of the local swamps and eventually forced to withdraw. A few months later Pepin himself died, apparently as a result of a disease contracted there.

Venice thus achieved lasting independence by repelling the besiegers. This was confirmed in an agreement between Charlemagne and Nicephorus which recognized Venice as Byzantine territory and also recognized the city's trading rights along the Adriatic coast, where Charlemagne previously ordered the Pope to expel the Venetians from the Pentapolis.

Medioevo (Early Middle Ages)

The successors of Obelerio inherited a united Venice. By the Pax Nicephori (803), the two emperors had recognized Venetian de facto independence, while it remained nominally Byzantine in subservience. During the reigns of Agnello Participazio and his two sons, Venice grew into its modern form. Though Eraclean by birth, Agnello, first doge of the family, was an early immigrant to Rialto and his dogeship was marked by the expansion of Venice towards the sea via the construction of bridges, canals, bulwarks, fortifications, and stone buildings. The modern Venice, at one with the sea, was being born. Agnello was succeeded by his son Giustiniano, who brought the body of Saint Mark the Evangelist to Venice from Alexandria and made him the patron saint of Venice.

During the reign of the successor of the Participazio, Pietro Tradonico, Venice began to establish its military might which would influence many a later crusade and dominate the Adriatic for centuries, and signed a trade agreement with the Holy Roman Emperor Lothair I, whose privileges were later expanded by Otto I. Tradonico secured the sea by fighting Narentine and Saracen pirates. Tradonico's reign was long and successful (837 – 864), but he was succeeded by the Participazio and it appeared that a dynasty may have finally been established. Around 841, the Republic of Venice sent a fleet of 60 galleys (each carrying 200 men) to assist the Byzantines in driving the Arabs from Crotone, but failed.

Under Pietro II Candiano, Istrian cities signed an act of devotion to the Venetian rule. The autocratic, philo-Imperial Candiano dynasty was overthrown by a revolt in 972, and the populace elected doge Pietro I Orseolo; however, his conciliating policy was ineffective, and he resigned in favor of Vitale Candiano.

Starting from Pietro II Orseolo, who reigned from 991, attention towards the mainland was definitely overshadowed by a strong push towards control of Adriatic Sea. Inner strife was pacified, and trade with the Byzantine Empire boosted by the favorable treaty (Grisobolus or Golden Bull) with Emperor Basil II. The imperial edict granted Venetian traders freedom from taxation paid by other foreigners and the Byzantines themselves.

In the Ascension-day of the year 1000 a powerful fleet sailed from Venice, to resolve the problem of the Narentine pirates. The fleet visited all the main Istrian and Dalmatian cities, whose citizen, exhausted by the wars between the Croatian king Svetislav and his brother Cresimir, swore an oath of fidelity to Venice. the Main Narentine harbors (Lagosta, Lissa and Curzola) tried to resist, but they were conquered and destroyed (see: battle of Lastovo). The Narentine pirates were suppressed permanently and disappeared. Dalmatia formally remained under Byzantine rule, but Oseolo became "Dux Dalmatie" ("Duke of Dalmatia"), establishing the prominence of Venice over the Adriatic Sea.

He died in 1008; he was also responsible of the establishment of the "Marriage of the Sea" ceremony. At this time Venice had a firm control over the Adriatic Sea, strengthened by the expedition of Pietro's son Ottone in 1017, and had assumed a firm role of balance of power between the two major Empires.

During the long Investiture Controversy, an 11th-century dispute between Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor and Pope Gregory VII over who would control appointments of church officials, Venice remained neutral, and this caused some attrition of support from the Popes. Doge Domenico Selvo intervened in the war between the Normans of Apulia and the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos in favor of the latter, obtaining in exchange a bull declaring the Venetian supremacy in the Adriatic coast up to Durazzo, as well as "the exemption from taxes for his merchants in the whole Byzantine Empire", a considerable factor in the city-state's later accumulation of wealth and power serving as middlemen for the lucrative spice and silk trade that funneled through the Levant and Egypt along the ancient Kingdom of Axum and Roman-Indian routes via the Red Sea.

The war was not a military success, but with that act the city gained total independence. In 1084, Domenico Selvo led a fleet against the Normans, but he was defeated and lost 9 great galleys, the largest and most heavily armed ships in the Venetian navy.

Population

- -- 120,000

Cemeteries

Fortifications

Holy Ground

Churches

Convents

Monasteries

Inns

Landmarks

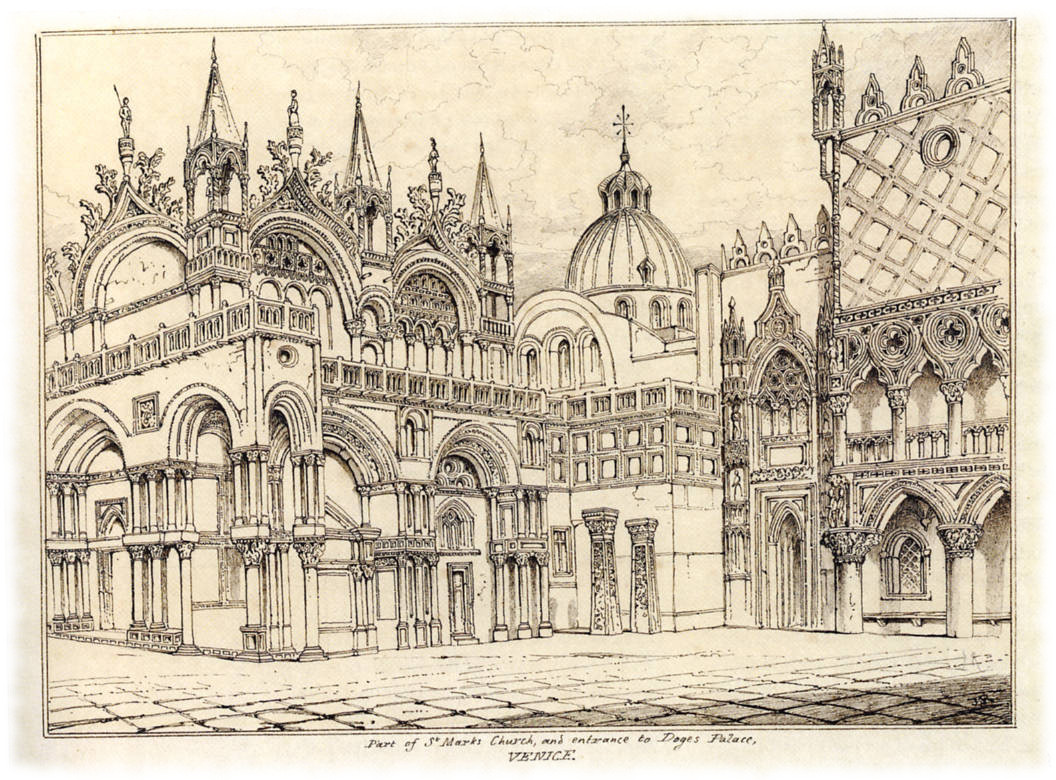

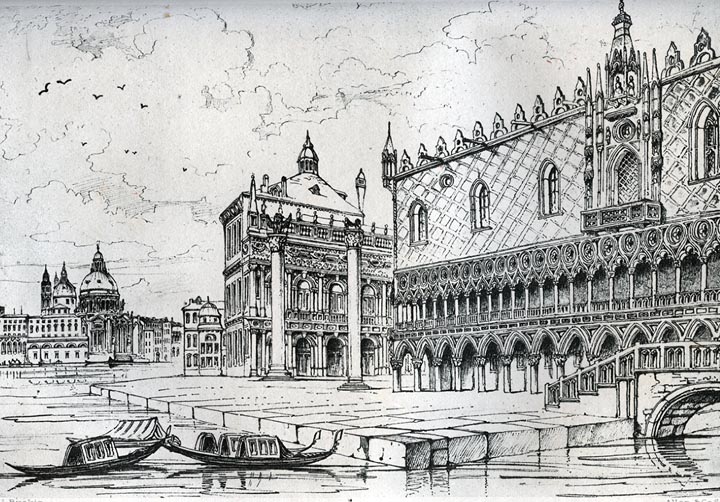

- -- Palazzo Ducale (The Doge's Palace)

- -- Rialto Bridge

Law & Lawlessness

Monuments

Private Residences

- -- Casa di Giovanni -- The Mausoleum

Taverns

Visitors

- Talib Samara -- Moorish Pirate

Whore Houses

The Vampires of Venice

High Clans

Brujah

- Natalya Svyatoslav -- Eastern Scholar

Cappadocians

- Goffredo Adimari -- A Cappadocian monk from

The Giovanni Bloodline

- Augustus Giovanni -- Third Generation Progenitor of the Giovanni Clan of Vampires

- Ambrogino Giovanni -- Giovanni Savant

- Ignazio Giovanni -- Scourge of Venice

Lasombra

- Narses -- Archbishop of Nod and Prince of Venice

- Alfonzo of Venice -- The Merchant Princeling

- Magdalena Castellucci Borcellino -- Night's Daughter

- Guilelmo Aliprando -- Seneschal of Venice

- Tommaso Brexiano -- Messenger of the Amicus Noctis

- Khadijah Saadeh -- Ashirra Envoy

Toreador

- Vasileios Michelakis -- Artisan of Glass

Ventrue

- Lanzo von Sachsen -- Ambassador of the Fiefs of the Black Cross to Venice

Low Clans

Assamites

Followers of Set

- Sarrasine -- Byzantine Envoy

Gangrel

- Marie Feroux -- Mother of Shame

Nosferatu

- Nicolo -- Wretch of Venice

Tremere

- Fredrich von München -- Thaumaturgic tutor to Augustus Giovanni, resident of the Venetian Ghetto in the Sestieri Cannaregio.

Cainite Criminals

- Jela Kovač -- Il drago di Murano -- {Serbian Tzimisce}

- Eadwulf -- The Huntsman - {Saxon Ventrue} -- Now posing as the mortal Captain Marko of the Isle of Murano.

Websites

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venice

http://visualovation.typepad.com/theartofcarnivaleinvenice/2011/01/once-upon-a-mask-3.html {Golden Masks}