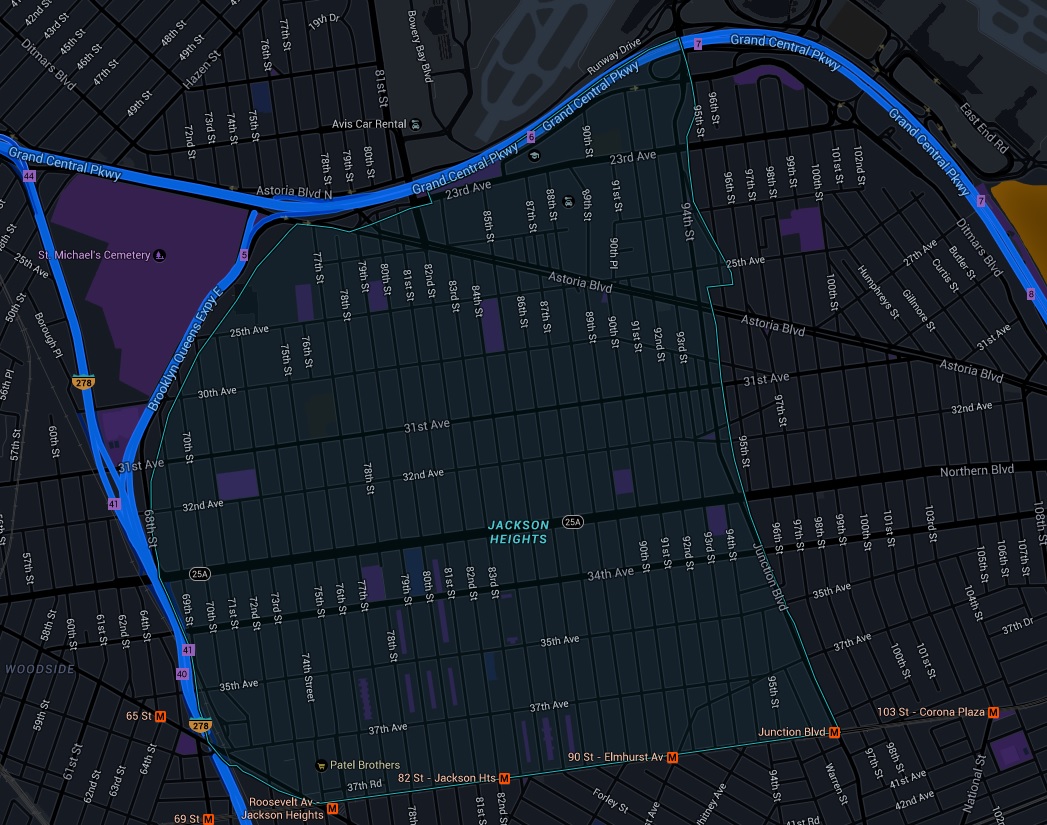

Jackson Heights - Queens

History

Early Years

The Jackson Heights name comes from Jackson Avenue, the former name for Northern Boulevard. John C. Jackson built the road across what is now Jackson Heights in 1859. The Jackson Avenue name is retained by this major road in a short stretch between Queens Plaza and Queens–Midtown Tunnel in Long Island City. The place was not actually high, but the name "heights" showed that the place was originally meant to be exclusive. Until 1916, the area was called "Trains Meadow", but contrary to the name, there were very few trains in the area. It is suspected that it was corrupted from "drain".

The first land purchase of 128 acres (52 ha) was completed in 1910, and Edward A. MacDougall's Queensboro Corporation had bought about 325 acres (132 ha) by 1914. At first, the area could only be reached via a ferry from Manhattan, but the Queensboro Bridge opened in 1909, followed by the elevated IRT Flushing Line—the present-day 7 trains, just 20 minutes from Manhattan—came in 1917, and Fifth Avenue Coach Company double-decker coaches came in 1922.

The Heights Develop

Jackson Heights was a planned development laid out by the Queensboro Corporation beginning in about 1916, and residents came after the arrival of the Flushing Line into Jackson Heights in 1917. The community was initially planned as a place for middle- to upper-middle income workers from Manhattan to raise their families. The Queensboro Corporation coined the name "garden apartment" to convey the concept of apartments surrounded by a green environment. The apartments, built around private parks during this time, contributed to Jackson Heights' being the first garden city community built in the United States, as part of the international garden city movement at the turn of the 20th century. Most of the buildings in Jackson Heights are the Queensboro Corporation apartments, built within a few blocks of the Flushing Line, which are typically five or six stories tall and are located between Northern Boulevard and 37th Avenue as part of that planned community. Targeted toward the middle class, the Queensboro Corporation-based the new apartments off of similar ones in Berlin. These new apartments were to share garden spaces, have ornate exteriors and features such as fireplaces, parquet floors, sun rooms, and built-in bathtubs with showers; and be cooperatively owned. In addition, the corporation divided the land into blocks and building lots, as well as installed streets, sidewalks, and power, water, and sewage lines. Although land for churches was provided, the apartments themselves were limited to white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, while excluding Jews, Blacks, and perhaps Greeks and Italians.

The Laurel apartment building on 82nd Street at Northern Boulevard was the first of the Queensboro Corporation buildings in Jackson Heights, completed in 1914 with a small courtyard. The Greystone on 79th Street between 34th Avenue and Northern Boulevard was completed in 1918 with a design by architect George H. Wells. There was leftover unused space, which was converted to parks, gardens, and recreational areas, including a golf course; much of this leftover space, including the golf course, no longer exists. This was followed by the 1919 construction of the Andrew J. Thomas-designed Linden Court, a 10-building complex between 84th Street, 85th Streets, 37th Avenue, and Roosevelt Avenue. The two sets of 5 buildings each, separated by a gated garden with linden trees and two pathways, included parking spaces with single-story garages accessed via narrow driveways, the first Jackson Heights development to do so; gaps at regular intervals in the perimeter wall; a layout that provided light and ventilation to the apartments, as well as fostered a sense of belonging to a community; the area's first co-op; and now-prevalent private gardens surrounded by the building blocks.

The Hampton Gardens, the Château, and the Towers followed in the 1920s. The Château and the Towers, both co-ops on 34th Avenue, had large, airy apartments and were served by elevators. The elegant Château cooperative apartment complex, with twelve building surrounding a shared garden, was built in the French Renaissance style and have slate mansard roofs pierced by dormer windows, and diaperwork brick walls. At first purely decorative, the shared gardens in later developments included paved spaces where people could meet or sit. The Queensboro Corporation started the Ivy Court, Cedar Court, and Spanish Gardens projects, all designed by Thomas, in 1924.

The Queensboro Corporation advertised their apartments from 1922 on. On August 28, 1922, the Queensboro Corporation paid $50 to the WEAF radio station to broadcast a ten-minute sales pitch for apartments in Jackson Heights, in what may have been the first "infomercial", opening with a few words about Nathaniel Hawthorne before promoting the corporation's Nathaniel Hawthorne apartments. The ad wanted viewers to: seek the recreation and the daily comfort of the home removed from the congested part of the city, right at the boundaries of God's great outdoors, and within a few minutes by subway from the business section of Manhattan ... The cry of the heart is for more living room, more chance to unfold, more opportunity to get near Mother Earth, to play, to romp, to plant and to dig ... Let me enjoin upon you as you value your health and your hopes and your home happiness, get away from the solid masses of brick ... where your children grow up starved for a run over a patch of grass and the sight of a tree...

Built in 1928, the English Gables line 82nd Street, the main shopping area of Jackson Heights' Hispanic community. There are two developments, called English Gables I and II; they were meant to provide a gateway to the neighborhood for commercial traffic and for passengers from the 82nd Street – Jackson Heights station. A year later, the Robert Morris Apartments, on 37th Avenue between 79th and 80th Streets, were constructed. Named after Robert Morris, a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence, the apartments have ample green spaces, original high ceilings, and fireplaces, and are relatively expensive.

The Decline of the Heights and Ethnic changes

Until the Great Depression, these apartments were only half-filled due to the paucity of residents who could pay; after the Depression, the apartments became more affordable. During the Depression, two new buildings were built: Ravenna Court on 37th Avenue between 80th and 81st Streets, built in 1929; and Georgian Court three blocks east, between 83rd and 84th Streets, built in 1930. The Queensboro Corporation began to build on land that until then had been kept open for community use, including the tennis courts, community garden, and the former golf course—located between 76th and 78th Streets and 34th and 37th Avenues—all of which were built upon during the 1940s and 1950s. The corporation also began erecting traditional six-story apartment buildings. Dunolly Gardens, the last garden apartment complex that Thomas built, was an exception, a modernistic building completed in 1939. The corner windows, considered very innovative in the 1930s, gave the apartments a more spacious feeling. After the 1940s, Jackson Heights's real estate was diversified, and more apartment buildings and cooperatives were built with elevators; some new transportation infrastructure were also built.

Primarily during the 1930s, Holmes Airport operated on 220 acres (0.89 km2) adjacent to the community, and later, its land became veterans' housing and the Bulova watch factory site.

By 1930, about 44,500 people lived in Jackson heights, an increase from 3,800 residents in 1910. The community was close-knit. Gay people from Broadway theaters started to move into the area. However, Jewish and black people were still excluded until Jews were allowed to move in by the 1940s and blacks by 1968. Beginning in the 1960s, an influx of newly immigrated residents came into Jackson Heights, at the same time that existing residents were leaving for suburbs due to white flight. Hispanic immigrants moved in by the 1970s. By then, white residents who remained in the neighborhood wished to eliminate the stigma of Jackson Heights being an ethnically diverse neighborhood, often defining its border as Roosevelt Avenue, because crime had started to increase in the area. By the mid-1970s, South American organized crime groups in Jackson Heights, often peddling drugs, gained national attention. A 1978 article in New York Magazine stated that 27 people were killed in Jackson Heights in the three years preceding.

Resident Vampires

- -- Adrian Cruz -- Toreador comic-book artist.