Compton Heights, St. Louis

In the 1760s, the village of Saint Louis resembled a medieval town in Europe. Its habitants lived within the confines of a fortified village and traveled each day to their prairie or cultivation fields, sometimes several miles away. Four major cultivating fields surrounded early Saint Louis: the St. Louis Common Field, Grande Prairie, Cul de Sac Prairie, and Prairie des Noyers. East of the Prairie des Noyers (present site of the Missouri Botanical Gardens) was another large tract of land known as the Saint Louis Commons. This tract was owned by all the villagers in common for the purposes of cutting firewood, pasturing livestock and hunting game. Never intended to be sold since it was held in common, its boundaries were not fixed because its area expanded as the population of St. Louis grew. Compton Heights occupies the Northwest corner of what was previously the Saint Louis Commons – its initial land partition was received in the 1850s.

This prarie, dotted with springs, limestone outcroppings, and rolling hills first belonged to prominent Saint Louisans, including: James S. Thomas, George I. Barnett, and Henry Shaw. In 1855, the city limits were expanded to include this area, just Southwest of downtown. The Compton Resevoir was completed in 1871, as the city's population continued to expand. Haarstick & The Compton Hill Improvement Company

Compton Heights is one of the earliest examples of planned residential developments of the American 19th century. The original "Compton Hill Improvement Company" was formed quietly in 1888 with a $400,000 investment (about $10m in today's terms) in the form of $100 shares by 33 individuals. Chief among the investors were Henry C. Haarstick (President of the Board) and Julius Pitzman (Secretary), both of whom lived on Russell Avenue (renamed from "Pontiac" in 1884). By 1890, over $300,000 had been spent in development including "above-street grading for each lot, sewers, gas and electric light, water, Telford pavements, Granitoid sidewalks, curb and gutter."

When the articles of association were renewed June 1, 1898, Haarstick dramatically increased his holdings from 150 shares in 1888 to 3,080 shares in 1898, giving him a dominant controlling interest in the Compton Hill Improvement Company. The number of shareholders had dropped from 33 to 7, all of which were members of the board of directors. Pitzman had also increased his holdings from 100 to 250, Herman Haeussler from 100 to 120 shares, Edward C. Kehr from 100 to 150. This new charter would last for 20 years, expiring June 1, 1918.

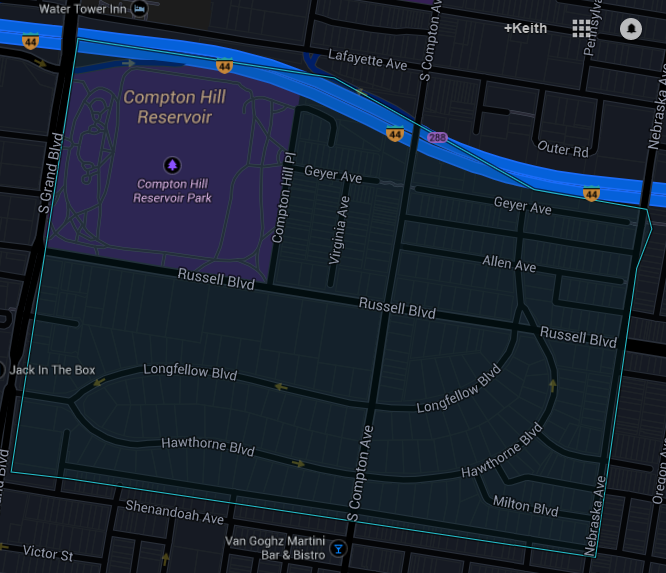

A main attraction of Compton Heights is the Compton Hill Reservoir Park.

St. Louis's rapid expansion in the late 19th century required construction of a vast system to bring fresh water to the burgeoning population. Five remarkable structures from that time period survive today and bear witness to the wealth of the city in that era. They include three standpipe towers, and two water intake structures in the middle of the Mississippi River.

At the end of the 19th century, there were several hundred standpipe towers scattered across the United States. With many having vanished over the years, St. Louis is fortunate to have three survivors. (Chicago's Michigan Avenue water tower, located in downtown Chicago, is famed and revered as a cherished city landmark. Other survivors include Milwaukee's Yankee Point tower on the northern lakefront, and towers in New York City and Louisville.) Though they are less known than their Chicago cousin, St. Louis's Victorian-era standpipes are of a much larger scale. All are well-preserved and exquisitely beautiful.

The two intake towers stand at the northeast edge of the city, off shore from the Riverview, St. Louis neighborhood, in the center of the Mississippi River's churning waters. They are no longer in service, and in fact can no longer be reached by boat due to shifts in the river's currents and rapids.