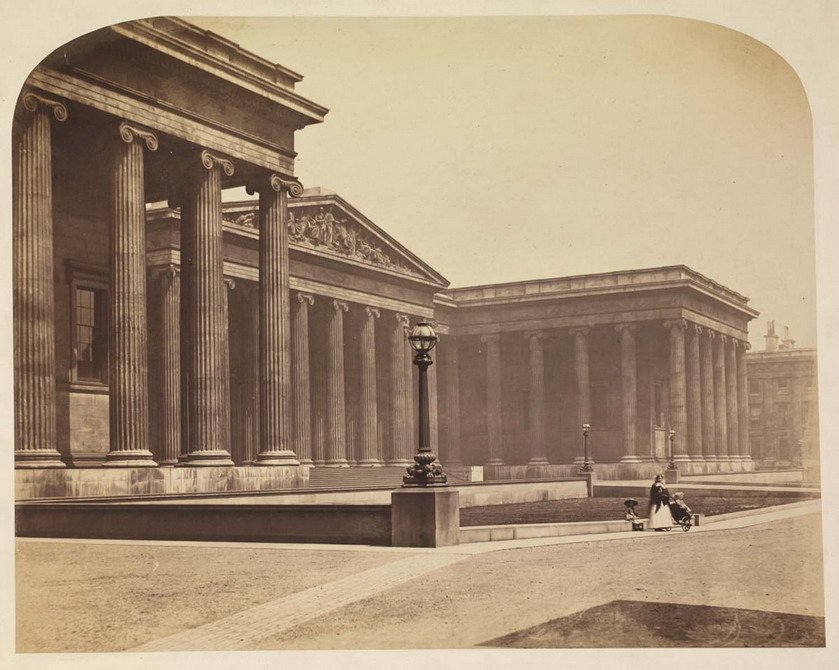

The British Museum

- London ~MDCCCLXXXVIII~ London 1888 ~MCM~ London - Pax Britannica

Introduction

The British Museum, in the Bloomsbury area of London, United Kingdom, is a public institution dedicated to human history, art and culture. Its permanent collection of some eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence, having been widely sourced during the era of the British Empire. It documents the story of human culture from its beginnings to the present. It was the first public national museum in the world.

The British Museum was established in 1753, largely based on the collections of the Irish physician and scientist Sir Hans Sloane. It first opened to the public in 1759, in Montagu House, on the site of the current building. Its expansion over the following 250 years was largely a result of expanding British colonisation and has resulted in the creation of several branch institutions, the first being the Natural History Museum in 1881.

In 1973, the British Library Act 1972 detached the library department from the British Museum, but it continued to host the now separated British Library in the same Reading Room and building as the museum until 1997. The museum is a non-departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, and as with all national museums in the UK it charges no admission fee, except for loan exhibitions.

Its ownership of some of its most famous objects originating in other countries is disputed and remains the subject of international controversy, most notably in the case of the Parthenon Marbles.

History

Sir Hans Sloane

Although today principally a museum of cultural art objects and antiquities, the British Museum was founded as a "universal museum". Its foundations lie in the will of the Irish physician and naturalist Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), a London-based doctor and scientist from Ulster. During the course of his lifetime, and particularly after he married the widow of a wealthy Jamaican planter, Sloane gathered a large collection of curiosities and, not wishing to see his collection broken up after death, he bequeathed it to King George II, for the nation, for a sum of £20,000.

At that time, Sloane's collection consisted of around 71,000 objects of all kinds including some 40,000 printed books, 7,000 manuscripts, extensive natural history specimens including 337 volumes of dried plants, prints and drawings including those by Albrecht Dürer and antiquities from Sudan, Egypt, Greece, Rome, the Ancient Near and Far East and the Americas.

Foundation (1753)

On 7 June 1753, King George II gave his Royal Assent to the Act of Parliament which established the British Museum. The British Museum Act 1753 also added two other libraries to the Sloane collection, namely the Cottonian Library, assembled by Sir Robert Cotton, dating back to Elizabethan times, and the Harleian Library, the collection of the Earls of Oxford. They were joined in 1757 by the "Old Royal Library", now the Royal manuscripts, assembled by various British monarchs. Together these four "foundation collections" included many of the most treasured books now in the British Library including the Lindisfarne Gospels and the sole surviving manuscript of Beowulf.

The British Museum was the first of a new kind of museum – national, belonging to neither church nor king, freely open to the public and aiming to collect everything. Sloane's collection, while including a vast miscellany of objects, tended to reflect his scientific interests. The addition of the Cotton and Harley manuscripts introduced a literary and antiquarian element and meant that the British Museum now became both National Museum and library.

Cabinet of curiosities (1753–1778)

The body of trustees decided on a converted 17th-century mansion, Montagu House, as a location for the museum, which it bought from the Montagu family for £20,000. The trustees rejected Buckingham House, on the site now occupied by Buckingham Palace, on the grounds of cost and the unsuitability of its location.

With the acquisition of Montagu House, the first exhibition galleries and reading room for scholars opened on 15 January 1759. At this time, the largest parts of collection were the library, which took up the majority of the rooms on the ground floor of Montagu House and the natural history objects, which took up an entire wing on the second state storey of the building. In 1763, the trustees of the British Museum, under the influence of Peter Collinson and William Watson, employed the former student of Carl Linnaeus, Daniel Solander to reclassify the natural history collection according to the Linnaean system, thereby making the Museum a public centre of learning accessible to the full range of European natural historians. In 1823, King George IV[19] gave the King's Library assembled by George III, and Parliament gave the right to a copy of every book published in the country, thereby ensuring that the museum's library would expand indefinitely. During the few years after its foundation the British Museum received several further gifts, including the Thomason Collection of Civil War Tracts and David Garrick's library of 1,000 printed plays. The predominance of natural history, books and manuscripts began to lessen when in 1772 the museum acquired for £8,410 its first significant antiquities in Sir William Hamilton's "first" collection of Greek vases.

Indolence and energy (1778–1800)

From 1778, a display of objects from the South Seas brought back from the round-the-world voyages of Captain James Cook and the travels of other explorers fascinated visitors with a glimpse of previously unknown lands. The bequest of a collection of books, engraved gems, coins, prints and drawings by Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode in 1800 did much to raise the museum's reputation; but Montagu House became increasingly crowded and decrepit and it was apparent that it would be unable to cope with further expansion.

The museum's first notable addition towards its collection of antiquities, since its foundation, was by Sir William Hamilton (1730–1803), British Ambassador to Naples, who sold his collection of Greek and Roman artifacts to the museum in 1784 together with a number of other antiquities and natural history specimens. A list of donations to the museum, dated 31 January 1784, refers to the Hamilton bequest of a "Colossal Foot of an Apollo in Marble". It was one of two antiquities of Hamilton's collection drawn for him by Francesco Progenie, a pupil of Pietro Fabris, who also contributed a number of drawings of Mount Vesuvius sent by Hamilton to the Royal Society in London.

Growth and change (1800–1825)

In the early 19th century the foundations for the extensive collection of sculpture began to be laid and Greek, Roman and Egyptian artefacts dominated the antiquities displays. After the defeat of the French campaign in the Battle of the Nile, in 1801, the British Museum acquired more Egyptian sculptures and in 1802 King George III presented the Rosetta Stone – key to the deciphering of hieroglyphs. Gifts and purchases from Henry Salt, British consul general in Egypt, beginning with the Colossal bust of Ramesses II in 1818, laid the foundations of the collection of Egyptian Monumental Sculpture. Many Greek sculptures followed, notably the first purpose-built exhibition space, the Charles Towneley collection, much of it Roman Sculpture, in 1805. In 1806, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1799 to 1803 removed the large collection of marble sculptures from the Parthenon, on the Acropolis in Athens and transferred them to the UK. In 1816 these masterpieces of western art, were acquired by The British Museum by Act of Parliament and deposited in the museum thereafter. The collections were supplemented by the Bassae frieze from Phigaleia, Greece in 1815. The Ancient Near Eastern collection also had its beginnings in 1825 with the purchase of Assyrian and Babylonian antiquities from the widow of Claudius James Rich.

In 1802 a buildings committee was set up to plan for expansion of the museum, and further highlighted by the donation in 1822 of the King's Library, personal library of King George III's, comprising 65,000 volumes, 19,000 pamphlets, maps, charts and topographical drawings. The neoclassical architect, Sir Robert Smirke, was asked to draw up plans for an eastern extension to the museum "... for the reception of the Royal Library, and a Picture Gallery over it ..." and put forward plans for today's quadrangular building, much of which can be seen today. The dilapidated Old Montagu House was demolished and work on the King's Library Gallery began in 1823. The extension, the East Wing, was completed by 1831. However, following the founding of the National Gallery, London in 1824,[e] the proposed Picture Gallery was no longer needed, and the space on the upper floor was given over to the Natural history collections.