Palace of Versailles

Contents

Introduction

The Palace of Versailles, or simply Versailles, is a royal château in Versailles in the Île-de-France region of France. It is also known as the Château de Versailles.

When the château was built, Versailles was a country village; today, however, it is a wealthy suburb of Paris, some 20 kilometres (12 miles) southwest of the French capital. The court of Versailles was the centre of political power in France from 1682, when Louis XIV moved from Paris, until the royal family was forced to return to the capital in October 1789 after the beginning of the French Revolution. Versailles is therefore famous not only as a building, but as a symbol of the system of absolute monarchy of the Ancien Régime.

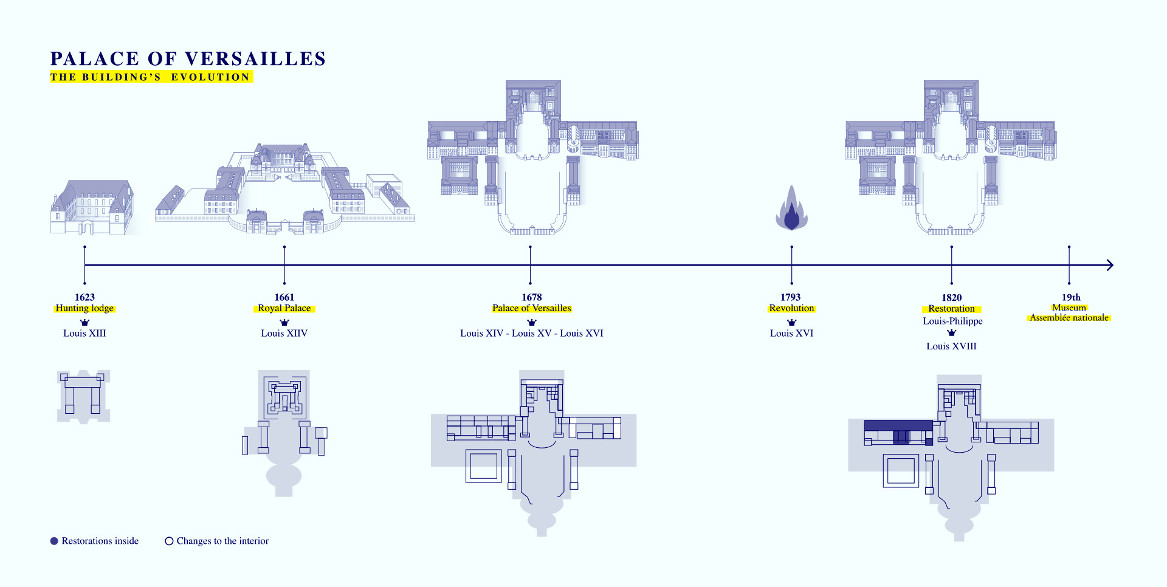

Palatial Evolutions

Origins

The earliest mention of the name of Versailles is found in a document which predates 1038, the Charte de l'abbaye Saint-Père de Chartres (Charter of the Saint-Père de Chartres Abbey), in which one of the signatories was a certain Hugo de Versailliis (Hugues de Versailles), who was seigneur of Versailles.

During this period, the village of Versailles centered on a small castle and church and the area was governed by a local lord. Its location on the road from Paris to Dreux and Normandy brought some prosperity to the village but, following an outbreak of the Plague and the Hundred Years' War, the village was largely destroyed and its population sharply declined. In 1575, Albert de Gondi, a naturalized Florentine who gained prominence at the court of Henry II, purchased the seigneury of Versailles.

Ancien Régime

Louis XIII

In the early seventeenth century, Gondi invited Louis XIII on several hunting trips in the forests surrounding Versailles. Pleased with the location, Louis ordered the construction of a hunting lodge in 1624. Designed by Philibert Le Roy, the structure, a small château, was constructed of stone and red brick with a based roof. Eight years later, Louis obtained the seigneury of Versailles from the Gondi family and began to make enlargements to the château.

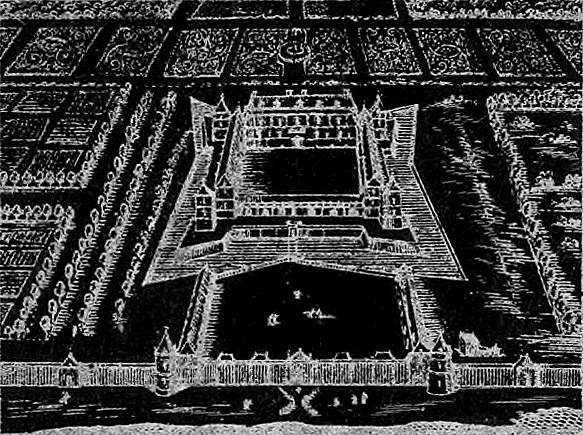

A vignette of Versailles from the 1652 Paris map of Jacques Gomboust (fr) shows a traditional design: an entrance court with a corps de logis on the far western end, flanked by secondary wings on the north and south sides, and closed off by an entrance screen. Adjacent exterior towers were located at the four corners with the entire structure surrounded by a moat. This was preceded by two service wings, creating a forecourt with a grilled entrance marked by two round towers. The vignette also shows a garden on the western side of the château with a fountain on the central axis and rectangular planted parterres to either side.

Louis XIV had played and hunted at the site as a boy. With a few modifications, this structure would become the core of the new palace.

Louis XIV

Louis XIII's successor, Louis XIV, had a great interest in Versailles. He settled on the royal hunting lodge at Versailles and over the following decades had it expanded into one of the largest palaces in the world. Beginning in 1661, the architect Louis Le Vau, landscape architect André Le Nôtre, and painter-decorator Charles Lebrun began a detailed renovation and expansion of the château. This was done to fulfill Louis XIV's desire to establish a new centre for the royal court. Following the Treaties of Nijmegen in 1678, he began to gradually move the court to Versailles. The court was officially established there on 6 May 1682.

By moving his court and government to Versailles, Louis XIV hoped to extract more control of the government from the nobility, and to distance himself from the population of Paris. All the power of France emanated from this centre: there were government offices here, as well as the homes of thousands of courtiers, their retinues, and all the attendant functionaries of court. By requiring that nobles of a certain rank and position spend time each year at Versailles, Louis prevented them from developing their own regional power at the expense of his own and kept them from countering his efforts to centralise the French government in an absolute monarchy. The meticulous and strict court etiquette that Louis established, which overwhelmed his heirs with its petty boredom, was epitomised in the elaborate ceremonies and exacting procedures that accompanied his rising in the morning, known as the Lever, divided into a petit lever for the most important and a grand lever for the whole court. Like other French court manners, étiquette was quickly imitated in other European courts.

The expansion of the château became synonymous with the absolutism of Louis XIV. In 1661, following the death of Cardinal Mazarin, chief minister of the government, Louis had declared that he would be his own chief minister. The idea of establishing the court at Versailles was conceived to ensure that all of his advisors and provincial rulers would be kept close to him. He feared that they would rise up against him and start a revolt. He thought that if he kept all of his potential threats near him, they would be powerless. After the disgrace of Nicolas Fouquet in 1661 – Louis claimed the finance minister would not have been able to build his grand château at Vaux-le-Vicomte without having embezzled from the crown – Louis, after the confiscation of Fouquet’s state, employed the talents of Le Vau, Le Nôtre, and Le Brun, who all had worked on Vaux-le-Vicomte, for his building campaigns at Versailles and elsewhere. For Versailles, there were four distinct building campaigns (after minor alterations and enlargements had been executed on the château and the gardens in 1662–1663), all of which corresponded to Louis XIV’s wars.

First building campaign

The first building campaign (1664–1668) commenced with the Plaisirs de l’Île enchantée of 1664, a fête that was held between 7 and 13 May 1664. The fête was ostensibly given to celebrate the two queens of France – Anne of Austria, the Queen Mother, and Marie-Thérèse, Louis XIV’s wife – but in reality honored the king’s mistress, Louise de La Vallière. The celebration of the Plaisirs de l’Île enchantée is often regarded as a prelude to the War of Devolution, which Louis waged against Spain. The first building campaign (1664–1668) involved alterations in the château and gardens to accommodate the 600 guests invited to the party.

Second building campaign

The second building campaign (1669–1672) was inaugurated with the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which ended the War of Devolution. During this campaign, the château began to assume some of the appearance that it has today. The most important modification of the château was Le Vau’s envelope of Louis XIII’s hunting lodge. The enveloppe – often referred to as the château neuf to distinguish it from the older structure of Louis XIII – enclosed the hunting lodge on the north, west, and south. The new structure provided new lodgings for the king and members of his family. The main floor – the piano nobile – of the château neuf was given over entirely to two apartments: one for the king, and one for the queen. The grand appartement du roi occupied the northern part of the château neuf and grand appartement de la reine occupied the southern part.

The western part of the enveloppe was given over almost entirely to a terrace, which was later enclosed with the construction of the Hall of Mirrors (Galerie des Glaces). The ground floor of the northern part of the château neuf was occupied by the appartement des bains, which included a sunken octagonal tub with hot and cold running water. The king’s brother and sister-in-law, the duke and duchesse d’Orléans occupied apartments on the ground floor of the southern part of the château neuf. The upper story of the château neuf was reserved for private rooms for the king to the north and rooms for the king’s children above the queen’s apartment to the south.

Significant to the design and construction of the grands appartements is that the rooms of both apartments are of the same configuration and dimensions – a hitherto unprecedented feature in French palace design. It has been suggested that this parallel configuration was intentional as Louis XIV had intended to establish Marie-Thérèse d’Autriche as queen of Spain, and thus thereby establish a dual monarchy. Louis XIV’s rationale for the joining of the two kingdoms was seen largely as recompense for Philip IV's failure to pay his daughter Marie-Thérèse’s dowry, which was among the terms of capitulation to which Spain agreed with the promulgation of the Treaty of the Pyrenees, which ended the war between France and Spain that began in 1635 during the Thirty Years’ War. Louis XIV regarded his father-in-law’s act as a breach of the treaty and consequently engaged in the War of Devolution.

Both the grand appartement du roi and the grand appartement de la reine formed a suite of seven enfilade rooms. Each room is dedicated to one of the then known celestial bodies and is personified by the appropriate Greco-Roman deity. The decoration of the rooms, which was conducted under Le Brun's direction depicted the “heroic actions of the king” and were represented in allegorical form by the actions of historical figures from the antique past (Alexander the Great, Augustus, Cyrus, etc.).

Third building campaign

With the signing of the Treaty of Nijmegen in 1678, which ended the Dutch War, the third building campaign at Versailles began (1678–1684). Under the direction of the architect, Jules Hardouin-Mansart, the Palace of Versailles acquired much of the look that it has today. In addition to the Hall of Mirrors, Hardouin-Mansart designed the north and south wings, which were used, respectively, by the nobility and Princes of the Blood, and the Orangerie. Le Brun was occupied not only with the interior decoration of the new additions of the palace, but also collaborated with Le Nôtre's in landscaping the palace gardens. As symbol of France’s new prominence as a European super-power, Louis XIV officially installed his court at Versailles in May 1682.

Fourth building campaign

Soon after the crushing defeat of the War of the League of Augsburg (1688–1697) and owing possibly to the pious influence of Madame de Maintenon, Louis XIV undertook his last building campaign at Versailles. The fourth building campaign (1699–1710) concentrated almost exclusively on construction of the royal chapel designed by Hardouin-Mansart and finished by Robert de Cotte and his team of decorative designers. There were also some modifications in the appartement du roi, namely the construction of the Salon de l’Œil de Bœuf and the King’s Bedchamber. With the completion of the chapel in 1710, virtually all construction at Versailles ceased; building would not be resumed at Versailles until some twenty one years later during the reign of Louis XV.

Louis XV

After the death of the Louis XIV in 1715, the five-year-old king Louis XV, the court, and the Régence government of Philippe d’Orléans returned to Paris. In May 1717, during his visit to France, the Russian czar Peter the Great stayed at the Grand Trianon. His time at Versailles was used to observe and study the palace and gardens, which he later used as a source of inspiration when he built Peterhof on the Bay of Finland west of Saint Petersburg.

During the reign of Louis XV, Versailles underwent transformation, but not on the scale that had been seen during the reign of Louis XIV. When the king and the court returned to Versailles in 1722, the first project was the completion of the Salon d'Hercule, which had been begun during the last years of Louis XIV's reign but was never finished due to the king’s death.

Significant among Louis XV’s contributions to Versailles were the petit appartement du roi; the appartements de Mesdames, the appartement du dauphin, and the appartement de la dauphine on the ground floor; and the two private apartments of Louis XV – petit appartement du roi au deuxième étage (later transformed into the appartement de Madame du Barry) and the petit appartement du roi au troisième étage – on the second and third floors of the palace. The crowning achievements of Louis XV’s reign were the construction of the Opéra and the Petit Trianon.

Equally significant was the destruction of the Escalier des Ambassadeurs (Ambassadors' Stair), the only fitting approach to the State Apartments, which Louis XV undertook to make way for apartments for his daughters.

The gardens remained largely unchanged from the time of Louis XIV; only the completion of the Bassin de Neptune between 1738 and 1741 was the most important legacy Louis XV made to the gardens. Towards the end of his reign, Louis XV, under the advice of Ange-Jacques Gabriel, began to remodel the courtyard façades of the palace. With the objective revetting the entrance of the palace with classical façades, Louis XV began a project that was continued during the reign of Louis XVI, but which did not see completion until the 20th century.

Louis XVI

In 1774, shortly after his ascension, Louis XVI ordered an extensive replanting of the bosquets of the gardens, since many of the century-old trees had died. Only a few changes to Le Nôtre's design were made: some bosquets were removed, others altered, including the Bains d'Apollon (north of the Parterre de Latone), which was redone after a design by Hubert Robert in anglo-chinois style (popular during the late 18th century), and the Labyrinthe (at the southern edge of the garden) was converted to the small Jardin de la Reine. In the interior of the palace, the library and the salon des jeux in the petit appartement du roi and the petit appartement de la reine, redecorated by Richard Mique for Marie-Antoinette, are among the finest examples of the style Louis XVI.