French Quarter

The French Quarter, also known as the Vieux Carré, is the oldest neighborhood in the city of New Orleans. After New Orleans (La Nouvelle-Orléans in French) was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the city developed around the Vieux Carré ("Old Square" in English), a central square. The district is more commonly called the French Quarter today, or simply "The Quarter," related to changes in the city with American immigration after the Louisiana Purchase. Most of the extant historic buildings were constructed either in the late 18th century, during the city's period of Spanish rule, or were built during the first half of the 19th century, after U.S. annexation and statehood.

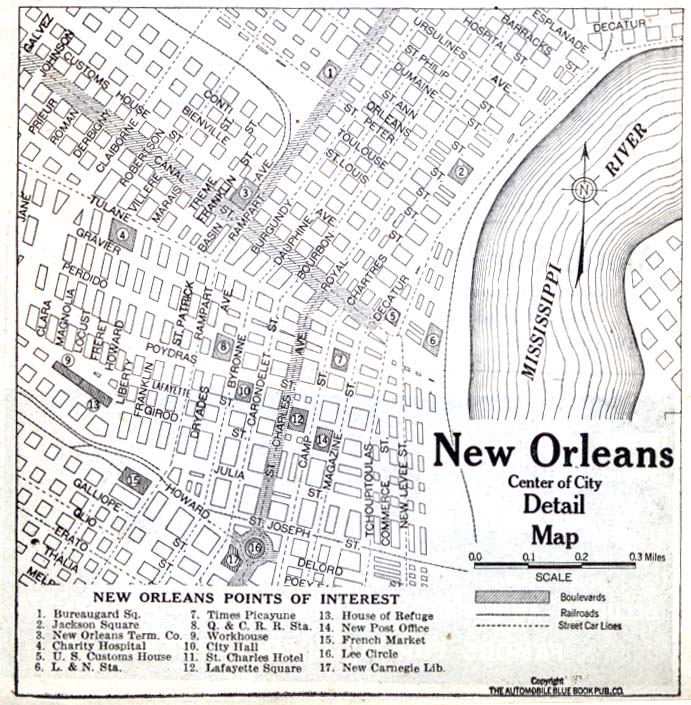

Boundaries

The most common definition of the French Quarter includes all the land stretching along the Mississippi River from Canal Street to Esplanade Avenue (13 blocks) and inland to North Rampart Street (seven to nine blocks). It equals an area of 78 square blocks. Some definitions, such as city zoning laws, exclude the properties facing Canal Street, which had already been redeveloped by the time architectural preservation was considered, and the section between Decatur Street and the river, much of which had long served industrial and warehousing functions.

Any alteration to structures in the remaining blocks is subject to review by the Vieux Carré Commission, which determines whether the proposal is appropriate for the historic character of the district. Its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Esplanade Avenue to the north, the Mississippi River to the east, Canal Street, Decatur Street and Iberville Street to the south and the Basin Street, St. Louis Street and North Rampart Street to the west.

The National Historic Landmark district is stated to be 85 square blocks. The Quarter is subdistrict of the French Quarter/CBD Area.

Significant Dates

Many of the buildings date from before 1803, when New Orleans was acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase, although some 19th-century and early 20th-century buildings were added to the area. Since the 1920s, the historic buildings have been protected by law and cannot be demolished; and any renovations or new construction in the neighborhood must be carried out in accordance with city regulations, preserving the historic architectural style.

Most of the French Quarter's architecture was built during the late 18th century and the period of Spanish rule over the city, which is reflected in the architecture of the neighborhood. The Great New Orleans Fire (1788) and another great fire in 1794 destroyed most of the Quarter's old French colonial architecture, leaving the colony's new Spanish overlords to rebuild it according to more modern tastes. Their strict new fire codes mandated that all structures be physically adjacent and close to the curb to create a firewall. The exception to that rule, The Cornstalk Hotel, also listed on the National Historical Register, still stands today at 915 Royal Street and is considered the finest Boutique Hotel in New Orleans. The old French peaked roofs were replaced with flat tiled ones, and wooden siding was banned in favor of fire-resistant stucco, painted in the pastel hues fashionable at the time. As a result, colorful walls and roofs and elaborately decorated ironwork balconies and galleries, from the late 18th and the early 19th centuries, abound. (In southeast Louisiana, a distinction is made between "balconies", which are self-supporting and attached to the side of the building, and "galleries," which are supported from the ground by poles or columns.)

When Anglophone Americans began to move in after the Louisiana Purchase, they mostly built on available land upriver, across modern-day Canal Street. This thoroughfare became the meeting place of two cultures, one Francophone Creole and the other Anglophone American. (Local landowners had retained architect and surveyor Barthelemy Lafon to subdivide their property to create an American suburb). The median of the wide boulevard became a place where the two contentious cultures could meet and do business in both French and English. As such, it became known as the "neutral ground", and this name is used for medians in the New Orleans area.

Even before the Civil War, French Creoles had become a minority in the French Quarter. In the late 19th century the Quarter became a less fashionable part of town, and many immigrants from southern Italy and Ireland settled there. In 1905, the Italian consul estimated that one-third to one-half of the Quarter’s population were Italian-born or second generation Italian-Americans. Irish immigrants also settled heavily in the Esplanade area, which was called the "Irish Channel".

The balconies and windows are an example of late 18th-century Spanish architecture built after the Great Fires of 1788 and 1794. In 1917, the closure of Storyville sent much of the vice formerly concentrated therein back into the French Quarter, which "for most of the remaining French Creole families . . was the last straw, and they began to move uptown." This, combined with the loss of the French Opera House two years later, provided a bookend to the era of French Creole culture in the Quarter. Many of the remaining French Creoles moved to the University area.

In the early 20th century, the Quarter's cheap rents and air of decay attracted a bohemian artistic community, a trend which became pronounced in the 1920s. Many of these new inhabitants were active in the first preservation efforts in the Quarter, which began around that time. As a result, the Vieux Carré Commission (VCC) was established in 1925. Although initially only an advisory body, a 1936 referendum to amend the Louisiana constitution afforded it a measure of regulatory power. It began to exercise more power in the 1940s to preserve and protect the district.

Meanwhile, World War II brought thousands of servicemen and war workers to New Orleans as well as to the surrounding region's military bases and shipyards. Many of these sojourners paid visits to the Vieux Carré. Although nightlife and vice had already begun to coalesce on Bourbon Street in the two decades following the closure of Storyville, the war produced a larger, more permanent presence of exotic, risqué, and often raucous entertainment on what became the city's most famous strip. Years of repeated crackdowns on vice in Bourbon Street clubs, which took on new urgency under Mayor deLesseps Story Morrison, reached a crescendo with District Attorney Jim Garrison's raids in 1962, but Bourbon Street's clubs were soon back in business.