Cairo -- medieval: Difference between revisions

| Line 494: | Line 494: | ||

=== <span style="color:#800000;">'''Banu Yashkur (سبط هيل) -- Assamites of Egypt''' === | === <span style="color:#800000;">'''Banu Yashkur (سبط هيل) -- Assamites of Egypt''' === | ||

[[]] | [[File:Assamites.jpg]] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 20:05, 21 February 2018

Quote (استشهد)

Mistress of broad provinces and fruitful lands, boundless in profusion

of buildings, peerless in beauty and splendor, she shelters all you will of the

learned and ignorant, the grave and the gay, the prudent and the foolish,

the noble and the base...like the waves of the sea she surges with her throngs

of folk...her youth is ever new despite the length of days. Her reigning star

never shifts from the mansion of fortune. (sic)

- -- Ibn Batuta, Rihla (The Journey)

- -- Ibn Batuta, Rihla (The Journey)

Admonition (تحذير)

Older than time itself, Cairo sits as a gleaming gem amid

the Egyptian sands. But is its glitter a beacon of hope or the

harbinger of something more terrible?

Appearance (مظهر)

Climate

Economy

History of the City Triumphant

Sins of the Fathers: A Secret History of Cairo

Time.

Long before my seminal mortal work, the Kitab al-Ibar, I was fascinated by its very concept -- where it comes from, what it signifies and, most importantly, what it (and its shortage) drives men to accomplish or ignore. When my sire first brought me into this world of eternal night, some six centuries ago now, my presumptions about time and "immortality" were, understandably, those that only a mortal could presume. Only now, having come this far through the long fog of history, do I even begin to see...

Time and the land of Egypt are, with little measure of overstatement, linked -- as brother and sister, as husband and wife. I pen this historical record as a living testament to them; to their scope, their ravages, their patience and deceit and, above all, the awesome power that is theirs to share. If it is a comprehensive history of either that you seek, be it mundane or otherwise, seek it elsewhere. I make no excuses about my designs for this brief account.

A strange mirror-tale to my work on humanity, it is equally as much the story of my kind as I have come to understand it. Cairo has borne the heavy load of the Damned for so long, and I believe that to learn from that suffering is a debt that is owed. Kindred find that many lessons can be learned in time...

I have heard it said that history is written by the victors. Alas, among the undead this is a curious fallacy: To the Children of Caine, history is truly written by those who have shaped its course -- and they are not always the victors.

May Allah bring ever-lasting peace and prosperity upon you.

-- Abd al-Rahman Ibn Khaldun, Walid Al-Muntathir

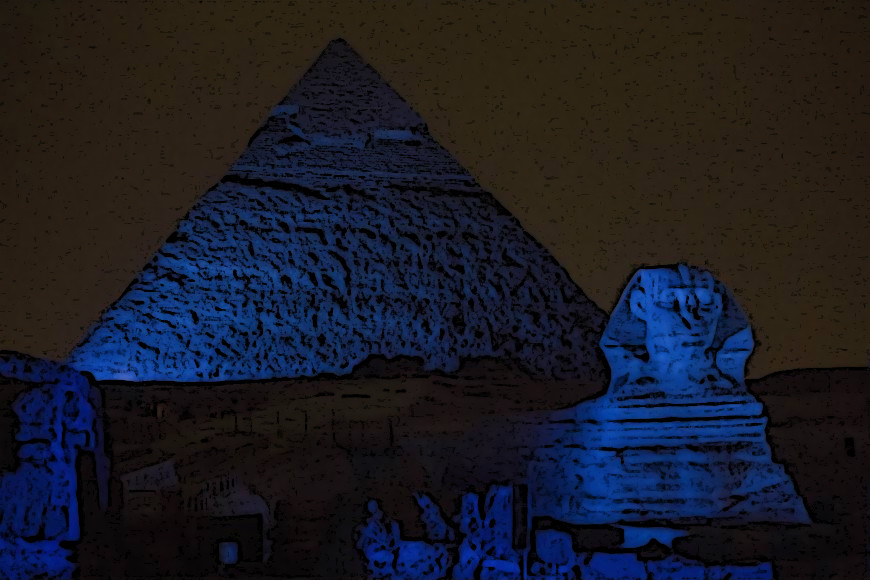

City of the Gods

Despite the early Egyptian belief that Creation began here in the form of a mound called benben, birthed by the gods eons ago from the void of nothingness, a more pragmatic (and less spectacular) view is more likely the case. Long ago, the land that was to become Egypt was, ironically, buried under an endless sea. Water, modern Egypt's most scant resource, was everything and everywhere. In time, the area gradually became a tropical forest, teeming with an abundance of flora and fauna. Life of all shapes and varieties, including many tribes of early humans, flocked to this budding paradise.

The first mortal inhabitants of the land they came to call Khem soon found that the price they would pay for Heaven on Earth was to live as obedient subjects to a host of deathless masters. In their wisdom, the gods had chosen to make the most beautiful land in Creation their home on the living plane. And it is in this place that their city arose, dotted with dazzling palaces and monuments of flawlessly worked stone. Here the gods rested long, hot days in private luxury, rising after nightfall to walk freely among their living worshipers.

Although the kine lived to serve (and, indeed, often served with their lives), the gratitude bestowed upon them for faithful service were wondrous indeed. From the gods themselves the mortals were taught new and more efficient way to make their living community thrive. Their sovereign lords instructed them, fittingly, on the arts of domestication and husbandry. These techniques were applied to everything possible, and thse ancient Egyptians had soon domesticated wheat, barley, sheep, goats, and cattle. Donkeys were put to use for transport, and pigs were kept in farms outside the city. One god in particular taught his subjects a deep reverence for all animals, and it is believed that from him that they learned to keep them as sacred aspects of the cycle of life. Some animals, such as the greyhound and the cat, were then given to the faithful as companions of their own -- to be taken in to live with them in their homes.

From the other gods, the mortals learned of community, love, early science and design. One game unto them the secret of flax, which was grown, spun into thread and woven into linen for the city's clothing. Another, presumably the designer of their own spectacular palaces, taught the people ways to live more securely, and soon their homes took on and even, rectangular shape, constructed of a much better brick. Another god poured his metalworking genius into their tools, which soon included harpoons, hoes, spindles, looms and drills for hollowing out stone vases. The people's use of flint for blades became more refined, and he assisted them in securing copper and other rare metals of the day. Yet another, one of the most favored among the kine by all accounts, took an active interest in their sense of community and pride. She encouraged recreation time to balance the heavy workload placed upon them, and was the most vocal proponent of leniency whenever transgressions occurred. One of her greatest gifts to them was a powerful oral tradition -- a method by which their songs and stories could live on through the ages -- and the many incarnations of this gift remain to this night.

As is also fitting, the gods gave unto their people a deep pandect of beliefs centered upon a strong religion. The dead, they were taught, were seen as holy -- to be treasured and revered by the living. Their were taught to sacrifice of themselves to those who passed on, and they supplied food and other items to the dead in their graves.

They chanted dirges to their fallen loved ones and observed holy days and nights in their names. Reverence for the lords of eternity and the afterlife that awaited them became paramount, and it is from this greatest of traditions that the greatest struggles would arise. This struggle -- would come to be known as the Jyhad.

A Brief History of Egypt

The history of Egypt has been long and rich, due to the flow of the Nile river, with its fertile banks and delta. Its rich history also comes from its native inhabitants and outside influence. Much of Egypt's ancient history was a mystery until the secrets of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs were deciphered with the discovery and help of the Rosetta Stone. The Great Pyramid of Giza is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still standing. The Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the other Seven Wonders, is gone. The Library of Alexandria was the only one of its kind for centuries.

Human settlement in Egypt dates back to at least 40,000 BC with Aterian tool manufacturing. Ancient Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh of the First Dynasty, Narmer. Predominately native Egyptian rule lasted until the conquering of Egypt by the Achaemenid Persian Empire in the 6th century BC.

In 332 BC, Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great conquered Egypt as he toppled the Achaemenids and established the Hellenistic Ptolemaic Kingdom, whose first ruler was one of Alexander's former generals, Ptolemy I Soter. The Ptolemies had to fight native rebellions and were involved in foreign and civil wars that led to the decline of the kingdom and its final annexation by Rome. The death of Cleopatra ended the nominal independence of Egypt resulting in Egypt becoming one of the provinces of the Roman Empire.

Roman rule in Egypt (including Byzantine) lasted from 30 BC to 641 AD, with a brief Sassanid Persian interlude between 619-629, known as Sasanian Egypt. After the Islamic conquest of Egypt, parts of Egypt became provinces of successive Caliphates and other Muslim dynasties: Rashidun Caliphate (632-661), Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), Abbasid Caliphate (750-909), Fatimid Caliphate (909-1171), Ayyubid Sultanate (1171–1260), and the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt (1250-1517).

Timeline

• 1st century BCE - Babylon Fortress built (approximate date).

• 4th-5th centuries CE - Saints Sergius and Bacchus Church (Abu Serga) built.

• 6th century - Church of Saint Menas established.

• 642 - Mosque of Amr ibn al-As built.

• 879 - Mosque of Ibn Tulun built.

• Church of St. George built (approximate date).

• Church of the Virgin Mary (Haret Zuweila) built (approximate date).

• 970

- • Misr al-Qahira settlement founded by Fatimid Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah.

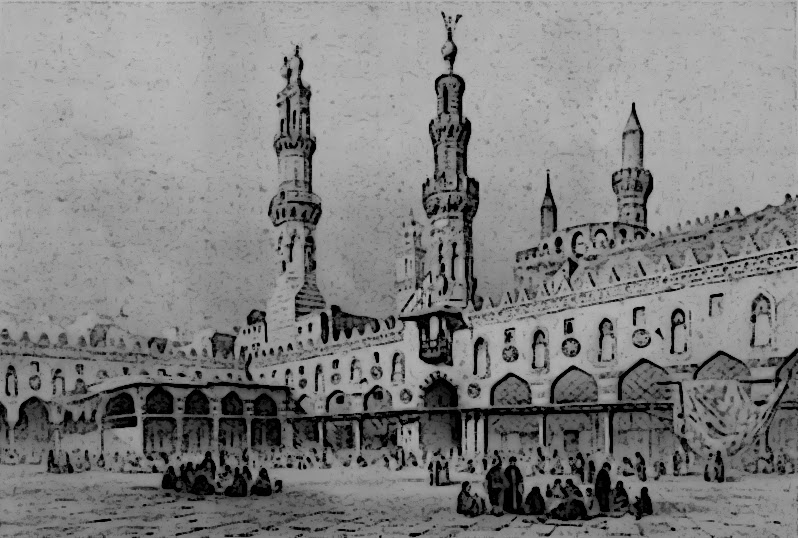

- • Al-Azhar University established.

• 972 - Al-Azhar Mosque established.

• 978 -The Hanging Church rebuilt (approximate date).

• 979 - Saint Mercurius Church in Coptic Cairo rebuilt (approximate date).

• 992 - Al-Hakim Mosque built.

• 11th century - Church of the Holy Virgin (Babylon El-Darag) built.

• 1016 - Lulua Mosque built.

• 1073 - Saint Barbara Church in Coptic Cairo restored.

• 1085 - Juyushi Mosque built.

• 1092 - City wall and Gates of Cairo built (including Bab Zuweila and Bab al-Nasr).

Medieval Cairo

Following the Islamic conquest in 639 AD, Lower Egypt was ruled at first by governors acting in the name of the Rashidun Caliphs and then the Ummayad Caliphs in Damascus, but in 747 the Ummayads were overthrown. In 1174, Egypt came under the rule of Ayyubids, which lasted until 1252.

The Ayyubids were overthrown by their bodyguards, known as the Mamluks, who ruled under the suzerainty of Abbasid Caliphs until 1517, when Egypt became part of the Ottoman Empire as Eyālet-i Mıṣr province.

The Muslim conquest of Egypt

n 639 an army of some 4,000 men were sent against Egypt by the second caliph, Umar, under the command of Amr ibn al-As. This army was joined by another 5,000 men in 640 and defeated a Byzantine army at the battle of Heliopolis. Amr next proceeded in the direction of Alexandria, which was surrendered to him by a treaty signed on November 8, 641. Alexandria was regained for the Byzantine Empire in 645 but was retaken by Amr in 646. In 654 an invasion fleet sent by Constans II was repulsed. From that time no serious effort was made by the Byzantines to regain possession of the country.

Administration of early Islamic Cairo

Following the first surrender of Alexandria, Amr chose a new site to settle his men, near the location of the Byzantine fortress of Babylon. The new settlement received the name of Fustat, after Amr's tent, which had been pitched there when the Arabs besieged the fortress. Fustat quickly became the focal point of Islamic Egypt, and, with the exception of the brief relocation to Helwan during a plague in 689, and the period of 750–763, when the seat of the governor moved to Askar, the capital and residence of the administration. After the conquest, the country was initially divided in two provinces, Upper Egypt (al-sa'id) and Lower Egypt with the Nile Delta (asfal al-ard). In 643/4, however, Caliph Uthman appointed a single governor (wāli) with jurisdiction over all of Egypt, resident at Fustat. The governor would in turn nominate deputies for Upper and Lower Egypt. Alexandria remained a distinct district, reflecting both its role as the country's shield against Byzantine attacks, and as the major naval base. It was considered a frontier fortress (ribat) under a military governor and was heavily garrisoned, with a quarter of the province's garrison serving there in semi-annual rotation. Next to the wāli, there was also the commander of the police (ṣāḥib al-shurṭa), responsible for internal security and for commanding the jund (army).

The main pillar of the early Muslim rule and control in the country was the military force, or jund, staffed by the Arab settlers. These were initially the men who had followed Amr and participated in the conquest. The followers of Amr were mostly drawn from Yamani (south Arabian) tribes, rather than the northern Arab (Qaysi) tribes, who were scarcely represented in the province; it was they who dominated the country's affairs for the first two centuries of Muslim rule. Initially, they numbered 15,500, but their numbers grew through emigration in the subsequent decades. By the time of Caliph Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680), the number of men registered in the army list (diwān al-jund) and entitled an annual pay (ʿaṭāʾ) reached 40,000. Jealous of their privileges and status, which entitled them to a share of the local revenue, the members of the jund then virtually closed off the register to new entries. It was only after the losses of the Second Fitna that the registers were updated, and occasionally, governors would add soldiers en masse to the lists as a means to garner political support.

In return for a tribute of money and food for the troops of occupation, the Christian inhabitants of Egypt were excused from military service and left free in the observance of their religion and the administration of their affairs.

Conversions of Copts to Islam were initially rare, and the old system of taxation was maintained for the greater part of the first Islamic century. The old division of the country into districts (nomoi) was maintained, and to the inhabitants of these districts demands were directly addressed by the governor of Egypt, while the head of the community—ordinarily a Copt but in some cases a Muslim Egyptian—was responsible for compliance with the demand.

Umayyad period

During the First Fitna, Caliph Ali (r. 656–661) appointed Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr as governor of Egypt, but Amr led an invasion in summer 658 that defeated Ibn Abi Bakr and secured the country for the Umayyads. Amr then served as governor until his death in 664. From 667/8 until 682, the province was governed by another fervent pro-Umayyad partisan, Maslama ibn Mukhallad al-Ansari. During the Second Fitna, Ibn al-Zubayr gained the support of the Kharijites in Egypt and sent a governor of his own, Abd al-Rahman ibn Utba al-Fihri, to the province. The Kharijite-backed Zubayrid regime was very unpopular with the local Arabs, who called upon the Umayyad caliph Marwan I (r. 684–685) for aid. In December 684, Marwan invaded Egypt and reconquered it with relative ease. Marwan installed his son Abd al-Aziz as governor. Relying on his close ties with the jund, Abd al-Aziz ruled the country for 20 years, enjoying wide autonomy and governing as a de facto viceroy. Abd al-Aziz also supervised the completion of the Muslim conquest of North Africa; it was he who appointed Musa ibn Nusayr in his post as governor of Ifriqiya. Abd al-Aziz hoped to be succeeded by his son, but when he died, Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (685–695) sent his own son, Abdallah, as governor in a move to reassert control and prevent the country from becoming a hereditary domain.

Abd al-Malik ibn Rifa'a al-Fahmi in 715 and his successor Ayyub ibn Sharhabil in 717 were the first governors chosen from the jund, rather than members of the Umayyad family or court. Both are reported to have increased pressure on the Copts, and initiated measures of Islamization. The resentment of the Copts against taxation led to a revolt in 725. In 727, to strengthen Arab representation, a colony of 3,000 Arabs was set up near Bilbeis. Meanwhile, the employment of the Arabic language had been steadily gaining ground, and in 706 it was made the official language of the government. Egyptian Arabic, the modern Arabic accent of Egypt, began to form. Other revolts of the Copts are recorded for the years 739 and 750, the last year of Umayyad domination. The outbreaks in all cases are attributed to increased taxation.

Abbasid period

The Abbasid period was marked by new taxations, and the Copts revolted again in the fourth year of Abbasid rule. At the beginning of the 9th century the practice of ruling Egypt through a governor was resumed under Abdallah ibn Tahir, who decided to reside at Baghdad, sending a deputy to Egypt to govern for him. In 828 another Egyptian revolt broke out, and in 831 the Copts joined with native Muslims against the government.

A major change came in 834, when Caliph al-Mu'tasim discontinued the practice of paying the jund as they nominally still formed the province's garrison—the ʿaṭāʾ from the local revenue. Al-Mu'tasim discontinued the practice, removing the Arab families from the army registers diwān and ordering that the revenues of Egypt be sent to the central government, which would then pay the ʿaṭāʾ only to the Turkish troops stationed in the province. This was a move towards centralizing power in the hands of the central caliphal administration, but also signaled the decline of the old elites, and the passing of power to the officials sent to the province by the Abbasid court, most notably the Turkish soldiers favored by al-Mu'tasim. At about the same time, for the first time the Muslim population began surpassing the Coptic Christians in numbers, and throughout the 9th century the rural districts were increasingly subject to both Arabization and Islamization. The rapidity of this process, and the influx of settlers after the discovery of gold and emerald mines at Aswan, meant that Upper Egypt in particular was only superficially controlled by the local governor. Furthermore, the persistence of internecine strife and turmoil at the heart of the Abbasid state—the so-called "Anarchy at Samarra" — led to the appearance of millennialist revolutionary movements in the province under a series of Alid pretenders in the 870s. In part, these movements were an expression of dissatisfaction with and alienation from imperial rule by Baghdad; these sentiments would manifest themselves in the support of several Egyptians for the Fatimids in the 10th century.

Tulunids, second Abbasid period, and Ikhsidids

In 868, Caliph al-Mu'tazz (r. 866–869) gave charge of Egypt to the Turkish general Bakbak. Bakbak in turn sent his stepson Ahmad ibn Tulun as his lieutenant and resident governor. This appointment ushered in a new era in Egypt's history: hitherto a passive province of an empire, under Ibn Tulun it would re-emerge as an independent political center. Ibn Tulun would use the country's wealth to extend his rule into the Levant, in a pattern followed by later Egypt-based regimes, from the Ikhshidids to the Mamluk Sultanate.

The first years of Ibn Tulun's governorship were dominated by his power struggle with the powerful head of the fiscal administration, the Ibn al-Mudabbir. The latter had been appointed as fiscal agent (ʿāmil) already since ca. 861, and had rapidly become the most hated man in the country as he doubled the taxes and imposed new ones on Muslims and non-Muslims alike. By 872 Ibn Tulun had achieved Ibn al-Mudabirbir's dismissal and taken over the management of the fisc himself, and had managed to assemble an army of his own, thereby becoming de facto independent of Baghdad. As a sign of his power, he established a new palace city to the northeast of Fustat, called al-Qata'i, in 870. The project was a conscious emulation of, and rival to, the Abbasid capital Samarra, with quarters assigned to the regiments of his army, a hippodrome, hospital, and palaces. The new city's centerpiece was the Mosque of Ibn Tulun. Ibn Tulun continued to emulate the familiar Samarra model in the establishment of his administration as well, creating new departments and entrusting them to Samarra-trained officials. His regime was in many ways typical of the "ghulām system" that became one of the two main paradigms of Islamic polities in the 9th and 10th centuries, as the Abbasid Caliphate fragmented and new dynasties emerged. These regimes were based on the power of a regular army composed of slave soldiers or ghilmān, but in turn, according to Hugh N. Kennedy, "the paying of the troops was the major preoccupation of government". It is therefore in the context of the increased financial requirements that in 879, the supervision of the finances passed to Abu Bakr Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Madhara'i, the founder of the al-Madhara'i bureaucratic dynasty that dominated the fiscal apparatus of Egypt for the next 70 years. The peace and security provided by the Tulunid regime, the establishment of an efficient administration, and repairs and expansions to the irrigation system, coupled with a consistently high level of Nile floods, resulted in a major increase in revenue. By the end of his reign, Ibn Tulun had accumulated a reserve of ten million dinars.

Ibn Tulun's rise was facilitated by the feebleness of the Abbasid government, threatened by the rise of the Saffarids in the east and by the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq itself, and divided due to the rivalry between Caliph al-Mu'tamid (r. 870–892) and his increasingly powerful brother and de facto regent, al-Muwaffaq. Open conflict between Ibn Tulun and al-Muwaffaq broke out in 875/6. The latter tried to oust Ibn Tulun from Egypt, but the expedition sent against him barely reached Syria. In retaliation, with the support of the Caliph, in 877/8 Ibn Tulun received responsibility for the entirety of Syria and the frontier districts of Cilicia (the Thughūr). Ibn Tulun occupied Syria but failed to seize Tarsus in Cilicia, and was forced to return to Egypt due to the abortive revolt of his eldest son, Abbas. Ibn Tulun has Abbas imprisoned, and named his second son, Khumarawayh, as his heir. In 882, Ibn Tulun came close to having Egypt become the new center of the Caliphate, when al-Mu'tamid tried to flee to his domains. In the event, however, the Caliph was overtaken and brought him back to Samarra (February 883) and under his brother's control. This opened anew the rift between the two rulers: Ibn Tulun organized an assembly of religious jurists at Damascus which denounced al-Muwaffaq a usurper, condemned his maltreatment of the Caliph, declared his place in the succession as void, and called for a jihād against him. Al-Muwaffaq was duly denounced in sermons in the mosques across the Tulunid domains, while the Abbasid regent responded in kind with a ritual denunciation of Ibn Tulun. Ibn Tulun then tried once more, again without success, to impose his rule over Tarsus. He fell ill on his return journey to Egypt, and died at Fustat on 10 May 884.

At Ibn Tulun's death, Khumarawayh, with the backing of the Tulunid elites, succeeded without opposition. Ibn Tulun bequeathed his heir "with a seasoned military, a stable economy, and a coterie of experienced commanders and bureaucrats". Khumarawayh was able to preserve his authority against the Abbasid attempt to overthrow him at the Battle of Tawahin and even made additional territorial gains, recognized in a treaty with al-Muwaffaq in 886 that gave the Tulunids the hereditary governorship over Egypt and Syria for 30 years. The accession of al-Muwaffaq's son al-Mu'tadid as Caliph in 892 marked a new rapprochement, culminating in the marriage of Khumarawayh's daughter to the new Caliph, but also the return of the provinces of Diyar Rabi'a and Diyar Mudar to caliphal control. Domestically, Khumarawayh's reign was one of "luxury and decay" (Hugh N. Kennedy), but also a time of relative tranquility in Egypt as well as in Syria, a rather unusual occurrence for the period. Nevertheless, Khumarawayh's extravagant spending exhausted the fisc, and by the time of his assassination in 896, the Tulunid treasury was empty. Following Khumarawayh's death, internal strife sapped Tulunid power. Khumarawayh's son Jaysh was a drunkard who executed his uncle, Mudar ibn Ahmad ibn Tulun; he was deposed after only a few months and replaced by his brother Harun ibn Khumarawayh. Harun too was a weak ruler, and although a revolt by his uncle Rabi'ah in Alexandria was suppressed, the Tulunids were unable to confront the attacks of the Qarmatians who began at the same time. In addition, many commanders defected to the Abbasids, whose power revived under the capable leadership of al-Muwaffaq's son, Caliph al-Mu'tadid (r. 892–902). Finally, in December 904, two other sons of Ibn Tulun, Ali and Shayban, murdered their nephew and assumed control of the Tulunid state. Far from halting the decline, this event alienated key commanders in Syria and led to the rapid and relatively unopposed reconquest of Syria and Egypt by the Abbasids under Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Katib, who entered Fustat in January 905. With the exception of the great Mosque of Ibn Tulun, the victorious Abbasid troops pillaged al-Qata'i and razed it to the ground.

In 969 the Fatimid general Jawhar as-Siqilli was placed at the head of an army said to number 100,000 men and attempted to seize Egypt. He had little difficulty defeating the Egyptian army. And on July 6, 969, he entered Fustat at the head of his forces. Egypt was transferred from the Eastern to the Western caliphate.

Fatimid period

Jawhar as-Siqilli immediately began the building of a new city, Cairo, to furnish quarters for the army which he had brought. A palace for the Caliph and a mosque for the army were immediately constructed, which for many centuries remained the center of Muslim learning. However, the Carmathians of Damascus under Hasan al-Asam advanced through Palestine to Egypt, and in the autumn of 971 Jauhar found himself besieged in his new city. By a timely sortie, preceded by the administration of bribes to various officers in the Carmathian host, Jauhar succeeded in inflicting a severe defeat on the besiegers, who were compelled to evacuate Egypt and part of Syria.

Meanwhile, the caliph al-Muizz had been summoned to enter the palace that had been prepared for him, and after leaving a viceroy to take charge of his western possessions he arrived in Alexandria on May 31 973, and proceeded to instruct his new subjects in the particular form of religion (Shiism) which his family represented. As this was in origin identical with that professed by the Carmathians, he hoped to gain the submission of their leader by argument; but this plan was unsuccessful, and there was a fresh invasion from that quarter in the year after his arrival, and the caliph found himself besieged in his capital.

The Carmathians were gradually forced to retreat from Egypt and then from Syria by some successful engagements, and by the judicious use of bribes, whereby dissension was sown among their leaders. Al-Muizz also found time to take some active measures against the Byzantines, with whom his generals fought in Syria with varying fortune. Before his death he was acknowledged as Caliph in Mecca and Medina, as well as Syria, Egypt and North Africa as far as Tangier.

Under the vizier al-Aziz, there was a large amount of toleration conceded to the other sects of Islam, and to other communities, but the belief that the Christians of Egypt were in league with the Byzantine emperor, and even burned a fleet which was being built for the Byzantine war, led to some persecution. Al-Aziz attempted without success to enter into friendly relations with the Buwayhid ruler of Baghdad, and tried to gain possession of Aleppo, as the key to Iraq, but this was prevented by the intervention of the Byzantines. His North African possessions were maintained and extended, but the recognition of the Fatimid caliph in this region was little more than nominal.

His successor al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah came to the throne at the age of eleven, being the son of Aziz by a Christian mother. His conduct of affairs was vigorous and successful, and he concluded a peace with the Byzantine emperor. He is perhaps best remembered by his destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem (1009), a measure which helped to provoke the Crusades, but was only part of a general scheme for converting all Christians and Jews in his dominions to his own opinions by force.

A more reputable expedient with the same end in view was the construction of a great library in Cairo, with ample provision for students; this was modeled on a similar institution at Baghdad. His system of persecution was not abandoned till in the last year of his reign (1020) he thought fit to claim divinity, a doctrine which is perpetuated by the Druze, called after one Darazi, who preached the divinity of al-Hakim at the time. For unknown reasons al-Hakim disappeared in 1021.

In 1049 the Zirid dynasty in the Maghrib returned to the Sunni faith and became subjects of the Caliphate in Baghdad, but at the same time Yemen recognized the Fatimid caliphate. Meanwhile, Baghdad was taken by the Turks, falling to the Seljuk Tughrul Beg in 1059. The Turks also plundered Cairo in 1068, but they were driven out by 1074. During this time, however, Syria was overrun by an invader in league with the Seljuk Malik Shah, and Damascus was permanently lost to the Fatimids. This period is otherwise memorable for the rise of the Hashshashin, or Assassins.

During the Crusades, al-Mustafa maintained himself in Alexandria, and helped the Crusaders by rescuing Jerusalem from the Ortokids, thereby facilitating its conquest by the Crusaders in 1099. He endeavored to retrieve his error by himself advancing into Palestine, but he was defeated at the battle of Ascalon, and compelled to retire to Egypt. Many of the Palestinian possessions of the Fatimids then successively fell into the hands of the Crusaders.

In 1118 Egypt was invaded by Baldwin I of Jerusalem, who burned the gates and the mosques of Farama, and advanced to Tinnis, when illness compelled him to retreat. In August 1121 al-Afdal Shahanshah was assassinated in a street of Cairo, it is said, with the connivance of the Caliph, who immediately began the plunder of his house, where fabulous treasures were said to be amassed. The vizier's offices were given to al-Mamn. His external policy was not more fortunate than that of his predecessor, as he lost Tyre to the Crusaders, and a fleet equipped by him was defeated by the Venetians.

In 1153 Ascalon was lost, the last place in Syria which the Fatimids held; its loss was attributed to dissensions between the parties of which the garrison consisted. In April 1154 the Caliph al-Zafir was murdered by his vizier Abbas, according to Usamah, because the Caliph had suggested to his favorite, the vizier's son, to murder his father; and this was followed by a massacre of the brothers of Zafir, followed by the raising of his infant son Abul-Qasim Isa to the throne.

In December 1162, the vizier Shawar took control of Cairo. However, after only nine months he was compelled to flee to Damascus, where he was favorably received by the prince Nureddin, who sent with him to Cairo a force of Kurds under Asad al-din Shirkuh. At the same time Egypt was invaded by the Franks, who raided and did much damage on the coast. Shawar recaptured Cairo but a dispute then arose with his Syrian allies for the possession of Egypt. Shawar, being unable to cope with the Syrians, demanded help of the Frankish king of Jerusalem Amalric I, who hastened to his aid with a large force, which united with Shawar's and besieged Shirkuh in Bilbeis for three months; at the end of this time, owing to the successes of Nureddin in Syria, the Franks granted Shirkuh a free passage with his troops back to Syria, on condition of Egypt being evacuated (October 1164).

Two years later Shirkuh, a Kurdish general known as "the Lion", persuaded Nureddin to put him at the head of another expedition to Egypt, which left Syria in January 1167; a Frankish army hastened to Shawar's aid. At the battle of Babain (April 11, 1167) the allies were defeated by the forces commanded by Shirkuh and his nephew Saladin, who was made prefect of Alexandria, which surrendered to Shirkuh without a struggle. In 1168 Amalric invaded again, but Shirkuh's return caused the Crusaders to withdraw.

Shirkuh was appointed vizier but died of indigestion (March 23, 1169), and the Caliph appointed Saladin as successor to Shirkuh; the new vizier professed to hold office as a deputy of Nureddin, whose name was mentioned in public worship after that of the Caliph. Nureddin loyally aided his deputy in dealing with Crusader invasions of Egypt, and he ordered Saladin to substitute the name of the Abbasid caliph for the Fatimid in public worship. The last Fatimid caliph died soon after in September, 1171.

Current Events

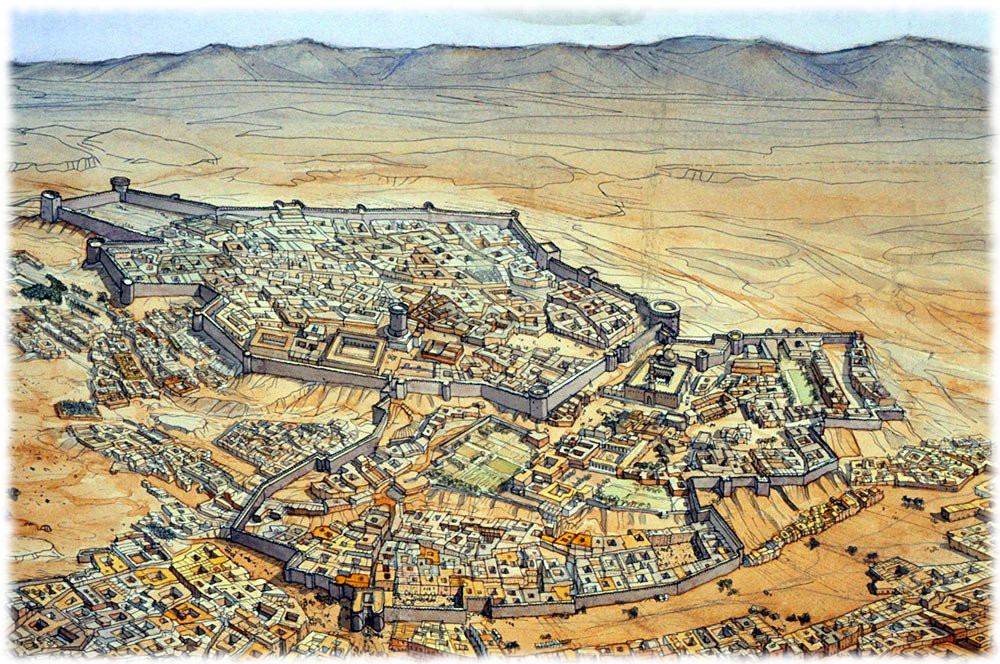

Districts of Al-Qāhirah

Аrea around present-day Cairo, especially Memphis, had long been a focal point of Ancient Egypt due to its strategic location just upstream from the Nile Delta. However, the origins of the modern city are generally traced back to a series of settlements in the first millennium. Around the turn of the 4th century, as Memphis was continuing to decline in importance, the Romans established a fortress town along the east bank of the Nile. This fortress, known as Babylon, remains the oldest structure in the city. It is also situated at the nucleus of the Coptic Orthodox community, which separated from the Roman and Byzantine church in the late 4th century. Many of Cairo's oldest Coptic churches, including the Hanging Church, are located along the fortress walls in a section of the city known as Coptic Cairo.

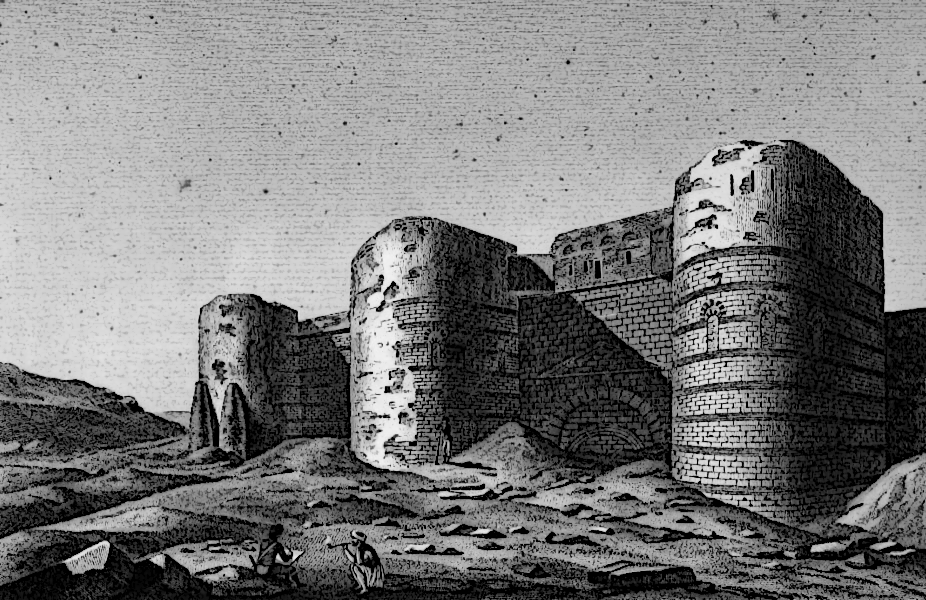

Babylon Fortress

There is evidence of settlement in the area as early as the 6th century BC, when Persians built a fort on the Nile, north of Memphis. The Persians also built a canal from the Nile (at Fustat) to the Red Sea. The Persian settlement was called Babylon, reminiscent of the ancient city along the Euphrates, and it gained importance while the nearby city of Memphis declined, as did Heliopolis. During the Ptolemaic period, Babylon and its people were mostly forgotten.

It is traditionally held that the Holy Family visited the area during the Flight into Egypt, seeking refuge from Herod. Further it is held that Christianity began to spread in Egypt when St. Mark arrived in Alexandria, becoming the first Patriarch, though the religion remained underground during the rule of the Romans. As the local population began to organize towards a revolt, the Romans, recognizing the strategic importance of the region, took over the fort and relocated it nearby as the Babylon Fortress. Trajan reopened the canal to the Red Sea, bringing increased trade, though Egypt remained a backwater as far as the Romans were concerned.

Under the Romans, St. Mark and his successors were able to convert a substantial portion of the population, from pagan beliefs to Christianity. As the Christian communities in Egypt grew, they were subjected to persecution by the Romans, under Emperor Diocletian around 300 AD, and the persecution continued following the Edict of Milan that declared religious toleration. The Coptic Church later separated from the church of the Romans and the Byzantines. Under the rule of Arcadius (395-408), a number of churches were built in Old Cairo.[8] In the early years of Arab rule, the Copts were allowed to build several churches within the old fortress area of Old Cairo.

In the 11th Century AD, Coptic Cairo hosted the Seat of the Coptic Orthodox Pope of Alexandria, which is historically based in Alexandria. As the ruling powers moved from Alexandria to Cairo after the Arab invasion of Egypt during Pope Christodolos's tenure, Cairo became the fixed and official residence of the Coptic Pope at the Hanging Church in Coptic Cairo in 1047.

The Ben Ezra Synagogue was established in Coptic Cairo in 1115, in what was previously a Coptic church that was built in the 8th century. The Copts needed to sell it, in order to raise funds to pay taxes to Ibn Tulun.

Important Sites of the Fortress of Babylon

- -- The Hanging Church -- Home to the Coptic Patriarch.

- -- Church of St. George in Cairo

- -- Coptic Orthodox Church of St. Barbara (or Sitt Barbara)

- -- Saints Sergius and Bacchus Church (AKA: Abu Serga)

- -- Saint Mercurius Church in Coptic Cairo

- -- Coptic Orthodox Church of Saint Menas (kenīset Mar-Mīna)

- -- Church of the Holy Virgin (AKA: Babylon El-Darag)

- -- Ben Ezra Synagogue

Rhoda Island

Al-Fustat

In 968, the Fatimids were led by General Jawhar al-Siqilli with his Kutama army, to establish a new capital for the Fatimid dynasty. Egypt was conquered from their base in Ifriqiya and a new fortified city northeast of Fustat was established. It took four years for Jawhar to build the city, initially known as al-Manṣūriyyah, which was to serve as the new capital of the caliphate. During that time, Jawhar also commissioned the construction of al-Azhar Mosque, which developed into the third-oldest university in the world. Cairo would eventually become a centre of learning, with the library of Cairo containing hundreds of thousands of books. When Caliph al-Mu'izz li Din Allah finally arrived from the old Fatimid capital of Mahdia in Tunisia in 973, he gave the city its present name, al-Qahira ("The Victorious").

For nearly 200 years after Cairo was established, the administrative centre of Egypt remained in Fustat. However, in 1168 the Fatimids under the leadership of Vizier Shawar set fire to Fustat to prevent Cairo's capture by the Crusaders. Egypt's capital was permanently moved to Cairo, which was eventually expanded to include the ruins of Fustat and the previous capitals of al-Askar and al-Qatta'i. While the Fustat fire successfully protected the city of Cairo, a continuing power struggle between Shawar, King Amalric I of Jerusalem, and the Zengid general Shirkuh led to the downfall of the Fatimid establishment.

In 1169 Saladin was appointed as the new vizier of Egypt by the Fatimids and two years later he would seize power from the family of the last Fatimid caliph, al-'Āḍid. As the first Sultan of Egypt, Saladin established the Ayyubid dynasty, based in Cairo, and aligned Egypt with the Abbasids, who were based in Baghdad. During his reign, Saladin also constructed the Cairo Citadel, which served as the seat of the Egyptian government until the mid-19th century.

In 1250 slave soldiers, known as the Mamluks, seized control of Egypt and like many of their predecessors established Cairo as the capital of their new dynasty. Continuing a practice started by the Ayyubids, much of the land occupied by former Fatimid palaces was sold and replaced by newer buildings. Construction projects initiated by the Mamluks pushed the city outward while also bringing new infrastructure to the centre of the city. Meanwhile, Cairo flourished as a centre of Islamic scholarship and a crossroads on the spice trade route among the civilisations in Afro-Eurasia. By 1340, Cairo had a population of close to half a million, making it the largest city west of China.

Al-Askar

al-‘Askar (Arabic: العسكر) was the capital of Egypt from 750-868, when Egypt was a province of the Abbasid Caliphate.

History

After the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 641, Rashidun commander Amr ibn al-As established Fustat just north of Coptic Cairo. At Caliph Umar's request, the Egyptian capital was moved from Alexandria to the new city on the eastern side of the Nile.

The reach of the Umayyads was extensive, stretching from western Spain all the way to eastern China. However, they were overthrown by the Abbasids, who moved the capital of the Umayyad empire itself to Baghdad. In Egypt, this shift in power involved moving control from the Umayyad city of al-Fustat slightly north to the Abbasid city of al-‘Askar. Its full name was مدينة العسكري Madinatu l-‘Askari "City of Cantonments" or "City of Sections". Intended primarily as a city large enough to house an army, it was laid out in a grid pattern that could be easily subdivided into separate sections for various groups such as merchants and officers.

The peak of the Abbasid dynasty occurred during the reign of Harun al Rashid, along with increased taxes on the Egyptians, who rose up in a peasant revolt in 832 during the time of Caliph al-Ma'mun. Local Egyptian governors gained increasing autonomy, and in 870, governor Ahmad ibn Tulun declared Egypt's independence (though still nominally under the rule of the Abbasid Caliph). As a symbol of this independence, in 868 ibn Tulun founded yet another capital, al-Qatta'i, slightly further north of al-‘Askar. The capital remained there until 905, until the city was destroyed, and the administrative capital of Egypt then returned to al-Fusṭāṭ.

Al-Fusṭāṭ itself was destroyed by a vizier-ordered fire that burned from 1168 to 1169, at which time the capital moved to nearly al-Qāhirah (Cairo), where it has remained to this day. Cairo's bounds grew to eventually encompass the three earlier capitals of al-Fusṭāṭ, al-Qatta'i and al-‘Askar, the remnants of which can today be seen in "Old Cairo" in the southern part of the city.

Places of Interest

- The Gorgon's Head -- A cheap place of ill repute, drink and inexpensive smoke -- Owned by Bilaal the Guide

Al-Qata'i

Al-Qaṭāʾi (Arabic: القطائـع) was the short-lived Tulunid capital of Egypt, founded by Ahmad ibn Tulun in the year 868 CE. Al-Qata'i was located immediately to the northeast of the previous capital, al-Askar, which in turn was adjacent to the settlement of Fustat. All three settlements were later incorporated into the city of al-Qahira (Cairo), founded by the Fatimids in 969 CE. The city was razed in the early 10th century CE, and the only surviving structure is the Mosque of Ibn Tulun.

History

Each of the new cities was founded with a change in the governance of the Middle East: Fustat was the first Arab settlement in Egypt, founded by Amr ibn al-A'as in 642 following the Arab conquest of Egypt. Al-Askar succeeded Fustat as capital of Egypt after the move of the caliphate from the Umayyad dynasty in Damascus to the Abbasids in Baghdad around 750 CE.

Al-Qata'i ("The Quarters") was established by Ahmad ibn Tulun when he was sent to Egypt by the Abbasid caliph to assume the governorship in 868 CE. Ibn Tulun arrived with a large military force that was too large to be housed in al-Askar. The city was founded on the Gabal Yashkhur, a hill to the northeast of the existing settlements that was said to have been the landing point for Noah's Ark after the Deluge, according to a local legend.

Al-Qata'i was modeled to some degree after Samarra in Iraq, where Ibn Tulun had undergone military training. Samarra was a city of sections, each designated for a particular social stratum or subgroup. Likewise, certain areas of al-Qata'i were allocated to officers, civil servants, specific military corps, Greeks, guards, policemen, camel drivers, and slaves. The new city was not intended to replace Fustat, which was a thriving market town, but rather to serve as an expansion of it. Many of the government officials continued to reside in Fustat.

The focal point of al-Qata'i was the large ceremonial mosque, named for Ibn Tulun, which is still the largest mosque in terms of area in Cairo. Among other architectural features, the mosque is noted for its use of pointed arches two centuries before they appeared in European architecture. The historian al-Maqrizi reported that a new mosque had to be built because the existing ceremonial mosque in Fustat, named for Amr ibn al-A'as, could not accommodate Ibn Tulun's personal regiment at the Friday prayer. Ibn Tulun's palace, the Dar al-Imara ("House of the Emir") was built adjacent to the mosque and a private door allowed the governor direct access to the pulpit, or minbar. The palace faced a large parade ground and park, featuring gardens and a hippodrome.

Ibn Tulun also commissioned the construction of an aqueduct to bring water to the existing town, and a maristan (hospital), the first such public institution in Egypt, founded in 873. An endowment was established to fund both in perpetuity. Ibn Tulun secured a significant income for the capital through various military campaigns, and many taxes were abolished during his rule. Following Ibn Tulun's death in 884, his son Khumarawayh focused much of his attention on enlarging the already lavish palace structures. He also built several irrigation canals and a sewage system in al-Qata'i.

In 905, Egypt was reoccupied by the Abbasids, and, in retaliation for the Tulunids long military campaigns against the caliphate, the city was plundered and razed, leaving only the mosque standing. Administration was then transferred back to al-Askar, which had become geographically indistinct from Fustat.

After the founding of al-Qahira in 969, Fustat/al-Askar and al-Qahira eventually grew together, building over the remains of the Tulunid capital and incorporating the Mosque of Ibn Tulun into the new urban landscape.

Places of Interest

- House of Fortune -- A gambling hall owned by one Toufik Abdulrashid

Al-Qāhirah

Population

- Annual Census, 1100 A.D.:

Bazaars

Cemeteries

The Cities of the Dead

Citizens of the City

Cairo is a city of communities. The city's residents both mortal and Kindred, often band together to accomplish individual and common goals, and the vampire who walks the streets of Cairo alone may well find herself at a distinct disadvantage. Within these assemblies lie various subsects, heresies and and fringe groups, and, when inspected in depth, their relations with one another can seem somewhat convoluted. To outsiders and those encountering them for the first time, their ancient and often traditional dealings with one another can appear peculiar, insular or unfamiliar.

Clergy

Craftsmen

Criminals

- -- Qadir Ali -- Experienced Smuggler

Fortifications

Holy Ground

Churches

Convents

Mosques

Inns

Law & Lawlessness

Monuments

Arches (Triumphal)

Bridges

Columns

Fountains

Gates

Mausolea

Statues

Tombs

Private Residences

How shall I go in peace and without sorrow? Nay, not without a wound

in the spirit shall I leave this city; long were the days of pain I have spent within

its walls, and long were the nights of aloneness, and who can depart from his

pain and his aloneness without regret? (sic)

- -- Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet

Taverns

Temples

Visitors

Whore Houses

Dead Among the Dead -- The Damned of Cairo (القتلى من بين الأموات - وملعون من القاهرة)

God Appears and God is Light

To those poor Souls who dwell in Night

But does a Human Form Display

To those who Dwell in Realms of day

-- William Blake, Auguries of Innocence

Introduction to the Unliving of Cairo

Banu Yashkur (سبط هيل) -- Assamites of Egypt

- -- Antara -- The Shepherd of Wolves

Banu Ahl ar-Raya (قبيلة من رمال الزمن) -- The Cold Brujah

- -- Al-Muntaqim - The Avenger

- -- Al-Muntathir - God's Witness

Qabilat Al-Mawt (قبيلة الموت) -- The Cappadocians of Cairo

Banu al as-Sa'idi (قبيلة من المصلين الثعبان) -- Followers of Set

- -- Bilaal the Guide -- Setite Entrepreneur

- -- Kahina -- Kahina is a powerful Setite Sorceress and one of the two heads of the Dream Court.

- -- Bek -- The Spice Merchant

Future Events: When Al-Fustat was destroyed in 1168 to prevent the King of Jerusalem from taking it for the Christians, so too fell the first and only legitimate domain ever held by the Followers of Set in Cairo. After that, they continued much as they always had, but without the benefit of an ancestral home and its attendant feeding rights.

Place of Note

Banu al - Lam'a (قبيلة من الليل) -- Lasombra

- -- Sharif Al-Lam'a -- Monarch of the Light

- -- Fatimah Al-Lam'a -- Pious Princess

- -- Suleiman ibn Abdullah -- Mullah of the Ashirra

Banu al - Hajji (سبط حجي) -- Muslim Nosferatu

- -- Wahid Al-Mufti -- The Sacred Legalist

- -- Fahim Hussain -- Scholar of Prophesy

- -- Tayyib -- The Good Samaritan

- -- Zaahir Najm -- The Hallowed One

Ventrue: Antonii cum Sanguine

- -- Antonius of Cairo -- Sultan of the City Victorious

Laibon (أبو الهول) -- The Sphinx of Cairo

- -- Jubal -- Advisor to the Sultan

Cainites of Lesser Blood

Shadows in Dust -- The Hidden Host

- -- Angelique -- Guardian of the Necropoli.

- -- [[]] --

- -- Maiden of Plagues -- The mysterious Sleeping Lord of the Cairene Court of Dreams.

- -- [[]] --

- -- Abu Al-Intiqam -- Child of Osiris

Ghouls and Future Cainites

Websites