Musée national du Moyen Âge: Difference between revisions

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

=== The Museum 1900 === | === The Museum 1900 === | ||

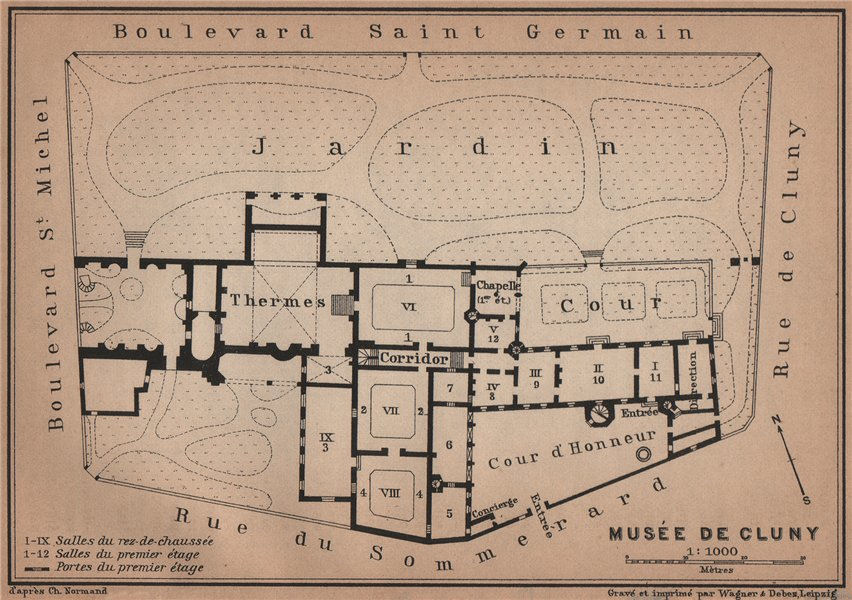

[[]] | [[File:Paris 1900 Musée national du Moyen Âge map.jpg]] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 11:46, 15 April 2017

History: The Hôtel de Cluny

The structure is perhaps the most outstanding example still extant of civic architecture in medieval Paris. It was formerly the town house (hôtel) of the abbots of Cluny, started in 1334. The structure was rebuilt by Jacques d'Amboise, abbot in commendam of Cluny 1485–1510; it combines Gothic and Renaissance elements. In 1843, it was made into a public museum, to hold relics of France's Gothic past preserved in the building by Alexandre du Sommerard.

Though it no longer possesses anything originally connected with the abbey of Cluny, the hôtel was at first part of a larger Cluniac complex that also included a building (no longer standing) for a religious college in the Place de la Sorbonne, just south of the present day Hôtel de Cluny along Boulevard Saint-Michel. Although originally intended for the use of the Cluny abbots, the residence was taken over by Jacques d'Amboise, Bishop of Clermont and Abbot of Jumièges, and rebuilt to its present form in the period of 1485-1500. Occupants of the house over the years have included Mary Tudor, the sister of Henry VIII of England. She resided here in 1515 after the death of her husband Louis XII, whose successor, Francis I, kept her under surveillance, particularly to see if she was pregnant. Seventeenth-century occupants included several papal nuncios, including Mazarin.

In the 18th century, the tower of the Hôtel de Cluny was used as an observatory by the astronomer Charles Messier who, in 1771, published his observations in the landmark Messier catalog. In 1789, the hôtel was confiscated by the state, and for the next three decades served several functions. At one point, it was owned by a physician who used the magnificent Flamboyant chapel on the first floor as a dissection room.

In 1833, Alexandre du Sommerard bought the Hôtel de Cluny and installed his large collection of medieval and Renaissance objects.[5] Upon his death in 1842, the collection was purchased by the state; the building was opened as a museum in 1843, with Sommerard's son serving as its first curator. The present-day gardens, opened in 1971, include a "forêt de la licorne" inspired by the tapestries.

The Hôtel de Cluny is partially constructed on the remnants of the third century Gallo-Roman baths (known as the Thermes de Cluny), famous in their own right, and which may be visited. In fact, the museum itself actually consists of two buildings: the frigidarium ("cooling room"), where the vestiges of the Thermes de Cluny are, and the Hôtel de Cluny itself, which houses its impressive collections.

The Museum 1900

The Musée de Cluny houses a variety of important medieval artifacts, in particular its tapestry collection, which includes the fifteenth century tapestry cycle La Dame à la Licorne.

Other notable works stored there include early medieval sculptures from the seventh and eighth centuries, and works of gold, ivory, antique furnishings, stained glass, and illuminated manuscripts.

Thermes de Cluny: The Roman Baths

The Thermes de Cluny are the ruins of Gallo-Roman thermal baths lying in the heart of Paris' 5th arrondissement, and which are partly subsumed into the Musée national du Moyen Âge - Thermes et hôtel de Cluny.

The present bath ruins constitute about one-third of a massive bath complex that is believed to have been constructed around the beginning of the 3rd century. The best preserved room is the frigidarium, with intact architectural elements such as Gallo-Roman vaults, ribs and consoles, and fragments of original decorative wall painting and mosaics.

It is believed that the bath complex was built by the influential guild of boatmen of 3rd-century Roman Paris or Lutetia, as the consoles on which the barrel ribs rest are carved in the shape of ships' prows. Like all Roman Baths, these baths were freely open to the public, and were meant to be, at least partially, a means of romanizing the ancient Gauls. As the baths lay across the Seine river on the Left Bank and were unprotected by defensive fortifications, they were easy prey to roving barbarian groups, who apparently destroyed the bath complex sometime at the end of the 3rd century.

The bath complex is partly an archaeological site, and has partly been incorporated into the Musée national du Moyen Age (or Musée de Cluny). It is the occasional repository for historic stonework or masonry found from time to time in Paris. The spectacular frigidarium is entirely incorporated within the museum and houses the Pilier des Nautes (Pillar of the Boatmen). Although somewhat obscured by renovations and reuse over the past two thousand years, several other rooms from the bath complex are also incorporated into the museum, notably the gymnasium, which now forms part of gallery 9 (Gallery of French Kings and sculptures from Notre Dame that were taken down during the iconoclasm of the French Revolution). The caldarium (hot water room) and the tepidarium (warm water room) are both still present as ruins outside the Musée and on the museum's grounds.

References in Literature

Herman Melville visited Paris in 1849, and the Hôtel de Cluny evidently fired his imagination. The structure figures prominently in Chapter 41 of Moby-Dick, when Ishmael, probing Ahab's "darker, deeper" motives, invokes the building as a symbol of man's noble but buried psyche.

In G. K. Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday, the narrator states (chapter 13) that the wealthy Dr. Renard's rooms "were like the Musée de Cluny".

Websites

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thermes_de_Cluny

http://www.musee-moyenage.fr/ang/index.html Home page (in English)

http://maget.maget.free.fr/SiteCluny/index3.html Sous les pavés…Paris Excellent Cluny web-site; check out the Axonometries and Tel quel sections, particularly.