Church of Saint-Sulpice: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

;[[Paris - La Belle Époque]] | ;[[Paris - La Belle Époque]] | ||

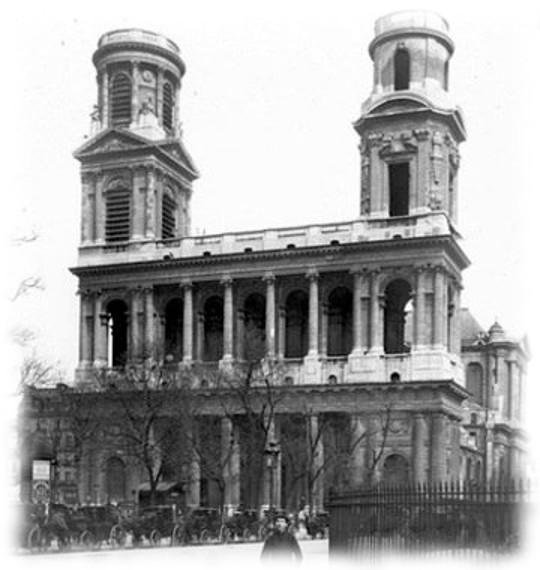

[[]] | [[File:Paris 1900 Church of Saint-Sulpice.jpg]] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Latest revision as of 19:30, 4 April 2017

The present church is the second building on the site, erected over a Romanesque church originally constructed during the 13th century. Additions were made over the centuries, up to 1631. The new building was founded in 1646 by parish priest Jean-Jacques Olier (1608–1657) who had established the Society of Saint-Sulpice, a clerical congregation, and a seminary attached to the church. Anne of Austria laid the first stone.

Construction began in 1646 to designs which had been created in 1636 by Christophe Gamard, but the Fronde interfered, and only the Lady Chapel had been built by 1660, when Daniel Gittard provided a new general design for most of the church. Gittard completed the sanctuary, ambulatory, apsidal chapels, transept, and north portal (1670–1678), after which construction was halted for lack of funds.

Gilles-Marie Oppenord and Giovanni Servandoni, adhering closely to Gittard's designs, supervised further construction (mainly the nave and side-chapels, 1719–1745). The decoration was executed by the brothers Sébastien-Antoine Slodtz (1695–1742) and Paul-Ambroise Slodtz (1702–1758).

In 1723–1724 Oppenord created the north and south portals of the transept with an unusual interior design for the ends: concave walls with nearly engaged Corinthian columns instead of the pilasters found in other parts of the church. He also built a bell-tower on top of the transept crossing (c. 1725), which threatened to collapse the structure because of its weight and had to be removed. This miscalculation may account for the fact that Oppenord was then relieved of his duties as an architect and restricted to designing decoration.

In 1732 a competition was held for the design of the west facade, won by Servandoni, who was inspired by the entrance elevation of Christopher Wren's Saint Paul's Cathedral in London. The 1739 Turgot map of Paris shows the church without Oppenord's crossing bell-tower, but with Servandoni's pedimented facade mostly complete, still lacking however its two towers.

Unfinished at the time of his death in 1766, the work was continued by others, primarily the obscure Oudot de Maclaurin, who erected twin towers to Servandoni's design. Servandoni's pupil Jean Chalgrin rebuilt the north tower (1777–1780), making it taller and modifying Servandoni's baroque design to one that was more neoclassical, but the French Revolution intervened, and the south tower was never replaced. Chalgrin also designed the decoration of the chapels under the towers.

The principal facade now exists in somewhat altered form. Servandoni's pediment, criticized as classically incorrect because its width was based on the entire front rather than the size of the order on which it rested, was removed after it was struck by lightning in 1770 and replaced with a balustrade. This change and the absence of the belvederes on the towers bring the design closer in spirit to that of the severely classical east front of the Louvre.

The facade is an unorthodox essay in which a double colonnade, Ionic order over Roman Doric with loggias behind them, unifies the bases of the corner towers with the façade; this fully classicising statement was made at the height of the rococo. Its revolutionary character was recognised by the architect and teacher Jacques-François Blondel, who illustrated the elevation of the façade in his Architecture françoise of 1752, remarking: "The entire merit of this building lies in the architecture itself... and its greatness of scale, which opens a practically new road for our French architects." Large arched windows fill the vast interior with natural light. The result is a simple two-storey west front with three tiers of elegant columns. The overall harmony of the building is, some say, only marred by the two mismatched towers.

Another point of interest dating from the time of the Revolution, when Christianity was suppressed and Saint-Sulpice became a place for worship of the "Supreme Being", is a printed sign over the center door of the main entrance. One can still barely make out the printed words ‘’Le Peuple Francais Reconnoit L’Etre Suprême Et L’Immortalité de L’Âme’’ ("The French people recognize the Supreme Being and the immortality of the soul"). Further questions of interest are the fate of the frieze that this must have replaced, the persons responsible for placing this manifesto and the reasons that it has been left in place.

During the Directory, Saint-Sulpice was used as a Temple of Victory. Redecorations to the interior, to repair extensive damage still remaining from the Revolution, were begun after the Concordat of 1801. Eugène Delacroix added murals (1855–1861) that adorn the walls of the Chapel of the Holy Angels (first side-chapel on the right). The most famous of these are Jacob Wrestling with the Angel and Heliodorus Driven from the Temple. During the Paris Commune one faction, called the Club de la Victoire, chose Saint-Sulpice as its headquarters and Louise Michel spoke from the pulpit.

The Marquis de Sade and Charles Baudelaire were baptized in Saint-Sulpice (1740 and 1821, respectively), and the church also saw the marriage of Victor Hugo to Adèle Foucher (1822). Louise Élisabeth de Bourbon and Louise Élisabeth d'Orléans, grand daughters of Louis XIV and Madame de Montespan are buried in the church. Louise de Lorraine, duchesse de Bouillon was buried here in 1788, wife of Charles Godefroy de La Tour d'Auvergne. Jules Massenet set an act of his opera Manon here.

The Organ

The church has a long-standing tradition of talented organists that dates back to the eighteenth century (see below). In 1862, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll reconstructed and improved the existing organ built by François-Henri Clicquot. The case was designed by Jean-François-Thérèse Chalgrin and built by Monsieur Joudot.

Though using many materials from Clicquot's French Classical organ, it is considered to be Cavaillé-Coll's magnum opus, featuring 102 speaking stops, and is perhaps the most impressive instrument of the romantic French symphonic-organ era.

Its organists have also been renowned, starting with Nicolas Séjan in the 18th century, and continuing with Charles-Marie Widor (organist 1870-1933) and Marcel Dupré (organist 1934-1971), both great organists and composers of organ music. Thus for over a century (1870–1971), Saint-Sulpice employed only two organists, and much credit is due to these two individuals for preserving the instrument and protecting it from the ravages of changes in taste and fashion which resulted in the destruction of many of Cavaillé-Coll's other masterpieces. The current organists are Daniel Roth (since 1985) and Sophie-Véronique Cauchefer-Choplin.

This impressive instrument is perhaps the summit of Cavaillé-Coll's craftmanship and genius. The sound and musical effects achieved in this instrument are almost unparalleled. Widor's compositional efforts for the organ were intended to produce orchestral and symphonic timbres, reaching the limits of the instrument's range. Albert Schweitzer, his student and collaborator—despite initiating an "Orgelbewegung," or organ reform movement, which deplored many nineteenth-century developments—called this organ the most beautiful in the world. More recently, Stephen Bicknell concurred, pointing out that the full ensemble of many large organs is dominated by a few powerful stops; but at S. Sulpice many ranks, each of moderate power, contribute to a sound of dazzling complexity.[22] With five manuals— keyboards— and boasting two 32-foot stops, organists at St. Sulpice have an incredibly rich palette of sounds at their disposal.

Aside from a re-arrangement of the manual keyboards c. 1900, the installation of an electric blower and the addition of two Pedal stops upon Widor's retirement in 1934 (Principal 16' and Principal 8' donated by Societe Cavaille-Coll), the organ is maintained today almost exactly as Cavaillé-Coll left it.

The Gnomon

In 1727 Jean-Baptiste Languet de Gergy, then priest of Saint-Sulpice, requested the construction of a gnomon in the church as part of its new construction, to help him determine the time of the equinoxes and hence of Easter. A meridian line of brass was inlaid across the floor and ascending a white marble obelisk, nearly eleven metres high, at the top of which is a sphere surmounted by a cross. The obelisk is dated 1743.

In the south transept window a small opening with a lens was set up, so that a ray of sunlight shines onto the brass line. At noon on the winter solstice (21 December), the ray of light touches the brass line on the obelisk. At noon on the equinoxes (21 March and 21 September), the ray touches an oval plate of copper in the floor near the altar.

Constructed by the English clock-maker and astronomer Henry Sully, the gnomon was also used for various scientific measurements: This rational use may have protected Saint-Sulpice from being destroyed during the French Revolution.