Greater Sudbury: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (1 revision) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 19:07, 3 January 2014

Quote

Appearance

City Coat of Arms

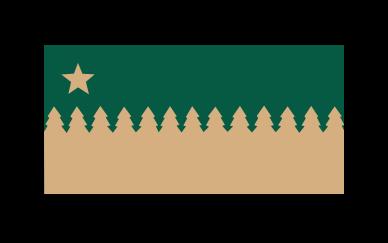

City Flag

City Logo

Climate

Greater Sudbury has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification). This region has warm and often hot summers with long, cold winters. It is situated north of the great lakes, making it prone to arctic air masses. Monthly precipitation is equal year round with snow cover expected six months of the year. Although extreme weather events are rare, Sudbury, Ontario Tornado - one of the worst tornadoes in Canadian history struck the city and its suburbs on August 20, 1970, killing six people, injuring 200, and causing over 17 million Canadian dollars in damages.

Economy

Geography

Sudbury has 330 lakes over 10 hectares (25 acres) within the city limits. The most prominent is Lake Wanapitei, the largest lake in the world completely contained within the boundaries of a single city, and which representing 1/3 of the total lake area. Lake Ramsey, a few kilometres south of downtown Sudbury, held the same record before the municipal amalgamation in 2001 brought Lake Wanapitei fully inside the city limits. Sudbury is divided into two main watersheds: to the east is the French River Watershed which flows into Georgian Bay and to the west is the Spanish River Watershed which flows into Lake Huron.

Sudbury is built around many small, rocky mountains with exposed igneous rock of the Canadian (Precambrian) Shield. The ore deposits in Sudbury are part of a large geological structure known as the Sudbury Basin, which are the remnants of a 1.85 billion-year-old meteorite impact crater. Sudbury's pentlandite, pyrite and pyrrhotite ores contain profitable amounts of many elements—primarily nickel and copper, but also platinum, palladium and other valuable metals.

Local smelting of the ore releases this sulphur into the atmosphere where it combines with water vapour to form sulphuric acid, contributing to acid rain. As a result, Sudbury is widely known as a wasteland. In parts of the city, vegetation was devastated by acid rain and logging to provide fuel for early smelting techniques. To a lesser extent, the area's ecology was also impacted by lumber camps in the area providing wood for the reconstruction of Chicago after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. While other logging areas in Northeastern Ontario were also involved in that effort, the emergence of mining related processes in the following decade made it significantly harder for new trees to grow to full maturity in the Sudbury area than elsewhere.

The resulting erosion exposed bedrock in many parts of the city, which was charred in most places to a pitted, dark black appearance. There was not a complete lack of vegetation in the region as Paper birch and wild blueberry patches thrived in the acidic soils. During the Apollo manned lunar exploration program, NASA astronauts trained in Sudbury to become familiar with impact breccia and shatter cones, rare rock formations produced by large meteorite impacts. However, the popular misconception that they were visiting Sudbury because it purportedly resembled the lifeless surface of the moon persists.

The city's Nickel District Conservation Authority operates a conservation area, the Lake Laurentian Conservation Area, in the city's south end. Other unique environmental projects in the city include the Fielding Bird Sanctuary, a protected area along Highway 17 near Lively that provides a managed natural habitat for birds, and a hiking and nature trail near Coniston, which is named in honour of scientist Jane Goodall.

Six provincial parks (Chiniguchi River, Daisy Lake Uplands, Fairbank, Killarney Lakelands and Headwaters, Wanapitei and Windy Lake) and two provincial conservation reserves (MacLennan Esker Forest and Tilton Forest) are also located partially or entirely within the city boundaries.

History

The Sudbury region was sparsely inhabited by the Ojibwe people of the Algonquin group as early as 9000 years ago following the retreat of the continental ice sheet. In 1856 the provincial land surveyor Albert Salter had located magnetic anomalies in the area that were strongly suggestive of mineral deposits, but his discovery aroused little attention because the area was remote. During construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1883, blasting and excavation revealed high concentrations of nickel-copper ore at Murray Mine on the edge of the Sudbury Basin, bearing out Salter's earlier readings. This brought the first waves of European settlers, who arrived not only to reap the benefits of the mineral-rich mines, but also to build a service station for railway workers. The parish was originally named Sainte-Anne-des-Pins ("St. Anne of the Pines") after a Jesuits mission concurrently established in the area. The Sainte-Anne-des-Pins church played a prominent role in the development of Franco-Ontarian culture in the region.

The community was named for Sudbury, Suffolk, in England, which was the hometown of Canadian Pacific Railway commissioner James Worthington's wife. Sudbury was incorporated as a town in 1893, and its first mayor was Stephen Fournier.

Thomas Edison visited the Sudbury area as a prospector in 1901, and is credited with the original discovery of the ore body at Falconbridge and rich deposits of nickel sulphide ore were discovered in the Sudbury Basin geological formation. The construction of the railway allowed exploitation of these mineral resources as well as large-scale lumber extraction. Artist's rendering of Sudbury in 1888

Mining began to replace lumber as the primary industry as improvements to the area's transportation network, including trams, made it possible for workers to live in one community and work in another. Sudbury’s economy was dominated by the mining industry for much of the 20th century. Two major mining companies were created, Inco in 1902 and Falconbridge in 1928. They became two of the city’s major employers and two of the world's leading producers of nickel.

Through the decades that followed, Sudbury's economy went through boom and bust cycles as world demand for nickel fluctuated. Demand was high during the First World War when Sudbury-mined nickel was used extensively in the manufacturing of artillery in Sheffield, England. It bottomed out when the war ended and then rose again in the mid-1920s as peacetime uses for nickel began to develop. The town was reincorporated as a city in 1930. The city recovered from the Great Depression much more quickly than almost any other city in North America due to increased demand for nickel in the 1930s. Sudbury was the fastest-growing city and one of the wealthiest cities in Canada for most of the decade. Many of the city's social problems in the Great Depression era were not caused by unemployment, but due to the difficulty in keeping up with all of its new infrastructure demands created by rapid growth. Between 1936 and 1941, the city was ordered into receivership by the Ontario Municipal Board. Another economic slowdown effected the city in 1937, but the city's fortunes rose again during the Second World War. The Frood Mine alone accounted for 40 percent of all the nickel used in Allied artillery production during the war. After the end of the war, Sudbury was in a good position to supply nickel to the United States government when it decided to stockpile non-Soviet supplies during the Cold War.

Compounded by open coke beds in the early to mid 20th century and logging for fuel, the area suffered a near-total loss of native vegetation. Consequently, the region became blanketed with exposed rocky outcrops permanently stained charcoal black, first by the air pollution from the roasting yards then by the acid rain in a layer which penetrates up to three inches into the once pink-gray granite. The construction of the Inco Superstack in 1972 dispersed sulphuric acid over a much wider area, reducing the acidity of local precipitation and enabling the city to begin an environmental recovery program. In the late 1970s, private and public interests combined to establish a "regreening" effort. Lime was spread over the charred soil by hand and by aircraft. Seeds of wild grasses and other vegetation were also spread. As of 2010, 9.2 million new trees have been planted in the city. Vale has begun to rehabilitate the slag heaps that surrounding their smelter in the Copper Cliff area with the planting of grass and trees.

In 1978, the workers of Sudbury's largest mining corporation, Inco (now Vale), embarked on a strike over production and employment cutbacks. The strike, which lasted for nine months, badly damaged Sudbury's economy and spurred the city government to launch a project to diversify the city's economy. Through an aggressive strategy, the city tried to attract new employers and industries through the 1980s and 1990s.

The city of Sudbury and its suburban communities, which were reorganized into the Regional Municipality of Sudbury in 1973, was subsequently merged in 2001 into the single-tier city of Greater Sudbury. In 2006, both of the city's major mining companies, Canadian-based Inco and Falconbridge, were taken over by new owners: Inco was acquired by the Brazilian company CVRD (now renamed Vale), while Falconbridge was purchased by the Swiss company Xstrata. Xstrata donated the historic Edison Building, the onetime head office of Falconbridge, to the city in 2007 to serve as the new home of the municipal archives. On September 19, 2008, a fire destroyed the historic Sudbury Steelworkers Hall on Frood Road. A strike at Vale's operations, which began on July 13, 2009, and saw a tentative resolution announced on July 5, 2010, lasted longer than the devastating 1978 strike, but had a much more modest effect on the city's economy than the earlier action—the local rate of unemployment declined slightly during the strike.

The ecology of the Sudbury region has recovered dramatically, helped by regreening programs and improved mining practices. The United Nations honoured twelve cities in the world, including Sudbury, with the Local Government Honours Award at the 1992 Earth Summit honouring the city's community-based environmental reclamation strategies. By 2010, the regreening programs had successfully rehabilitated 3,350 hectares of land in the city; however, approximately 30,000 hectares of land have yet to be rehabilitated.

Location

Population

- City (160,274) - 2011 census

- Metro Area (160,770) - 2011 census

- 2012 estimate: 95,000

- 2023 estimate: low 70,000s

Arenas

Attractions

Bars and Clubs

Castles

Cemeteries

City Government

Churches

Crime

Citizens of the City

Current Events

Galleries

Hospitals

Hotels & Hostels

Hypermarkets

Landmarks

Maps

Monasteries

Monuments

Museums

Neighborhoods

Parks

Private Residences

Restaurants

Ruins

Schools

Shops

Theatres

Transportation

Recent History

Sudbury played a major role in the recent Quebequois war for independence. First, it was a staging area for forces prepared to move against the separatists, then it was badly damaged by the Quebeqois' American allies, who bombed the city to prevent Canadian forces from advancing. As of 2022, the city's infrastructure has not been rebuilt, and the population has not yet recovered.