Novel 1920's New Orleans: Difference between revisions

| Line 582: | Line 582: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

* -- [[Andre Foushon]] <span style="color:#800000;"> Prince | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 12:14, 6 November 2015

Quote

"It is the most congenial city in America that I know of and it"

"is due in large part, I believe, to the fact that here at last on this bleak"

"continent that sensual pleasures assume the importance which they deserve..."

- -- Henry Miller, The Air-Conditioned Nightmare

- -- Henry Miller, The Air-Conditioned Nightmare

Appearance

Location

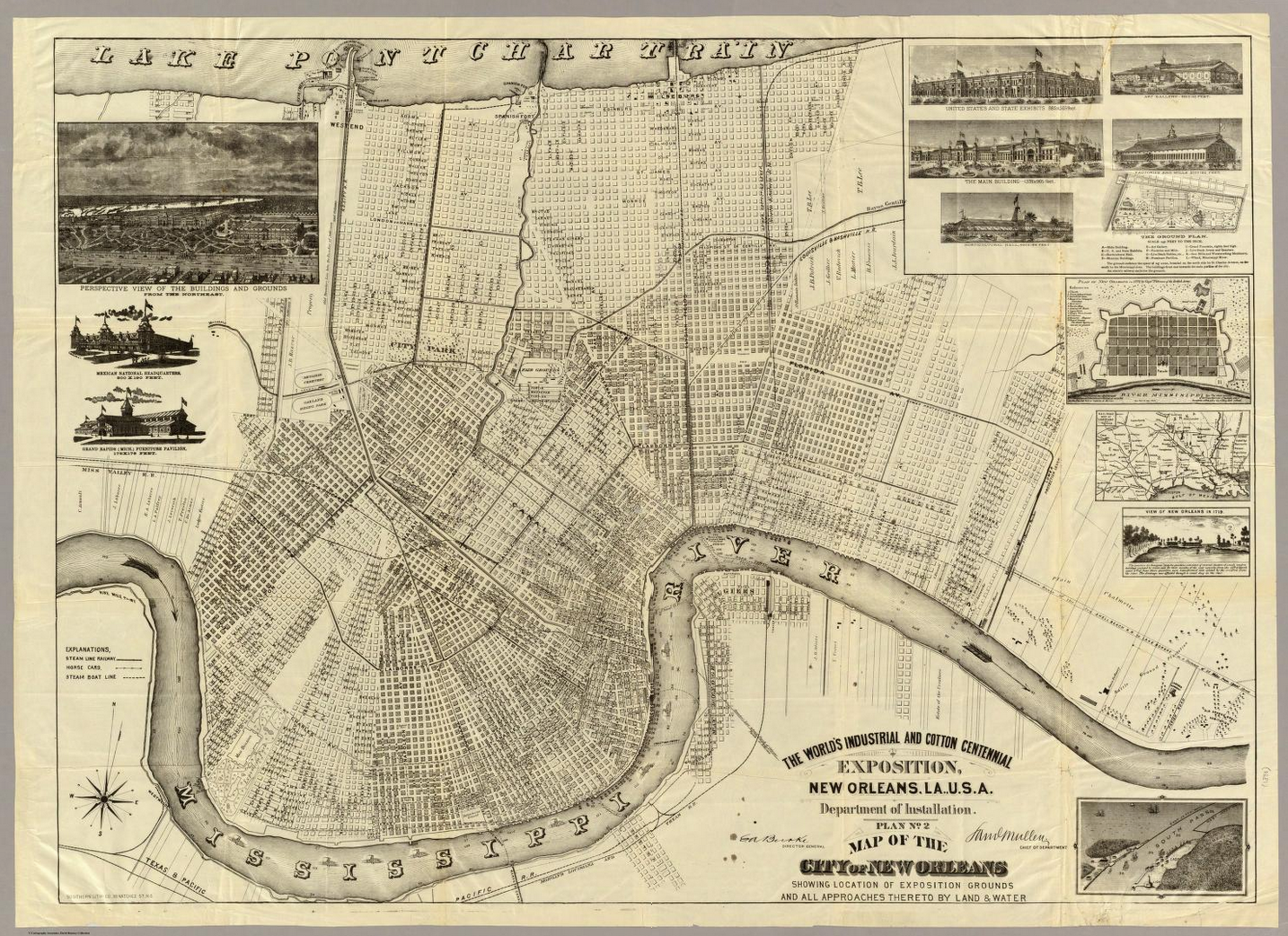

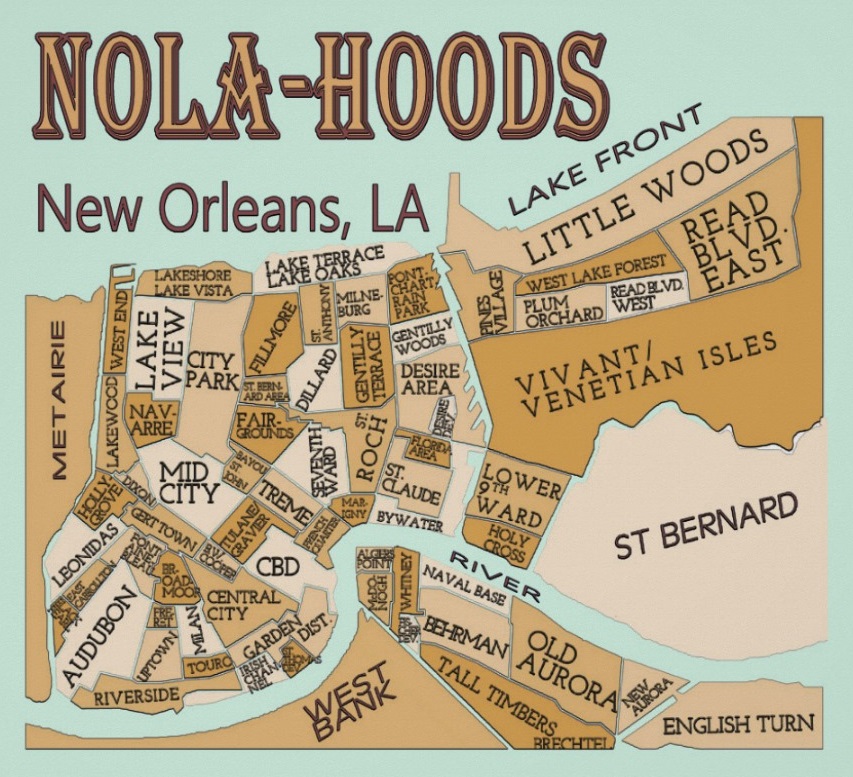

New Orleans is located at 29°57′53″N 90°4′14″W (29.964722, −90.070556) on the banks of the Mississippi River, approximately 105 miles (169 km) upriver from the Gulf of Mexico. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 350.2 square miles (907 km2), of which 180.56 square miles (467.6 km2), or 51.55%, is land. The city is located in the Mississippi River Delta on the east and west banks of the Mississippi River and south of Lake Pontchartrain. The area along the river is characterized by ridges and hollows.

Climate

The climate of New Orleans is humid subtropical with short, generally mild winters and hot, humid summers. The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 53.4 °F (11.9 °C) in January to 83.3 °F (28.5 °C) in July and August. The lowest recorded temperature was 6 °F (−14 °C) on February 13, 1899. The highest recorded temperature was 104 °F (40 °C) on June 24, 2009. The average precipitation is 62.7 inches (1,590 mm) annually; the summer months are the wettest, while October is the driest month. Precipitation in winter usually accompanies the passing of a cold front. On average, there are 77 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs, 8.1 days per winter where the high does not exceed 50 °F (10 °C), and 8.0 nights with freezing lows annually; in a typical year the coldest night will be around 30 °F (−1 °C).[62] It is rare for the temperature to reach 100 °F (38 °C) or dip below 25 °F (−4 °C).

Hurricanes pose a severe threat to the area, and the city is particularly at risk because of its low elevation, and because it is surrounded by water from the north, east, and south, and Louisiana's sinking coast. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, New Orleans is the nation's most vulnerable city to hurricanes. Indeed, portions of Greater New Orleans have been flooded by: the Grand Isle Hurricane of 1909, the New Orleans Hurricane of 1915, 1947 Fort Lauderdale Hurricane, Hurricane Flossy in 1956, Hurricane Betsy in 1965, Hurricane Georges in 1998, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, and Hurricane Gustav in 2008, with the flooding in Betsy being significant and in a few neighborhoods severe, and that in Katrina being disastrous in the majority of the city.

New Orleans experiences snowfall only on rare occasions. A small amount of snow fell during the 2004 Christmas Eve Snowstorm and again on Christmas (December 25) when a combination of rain, sleet, and snow fell on the city, leaving some bridges icy. Before that, the last White Christmas was in 1964 and brought 4.5 inches (11 cm). Snow fell again on December 22, 1989, when most of the city received 1–2 inches (2.5–5.1 cm).

The last significant snow fall in New Orleans was on the morning of December 11, 2008.

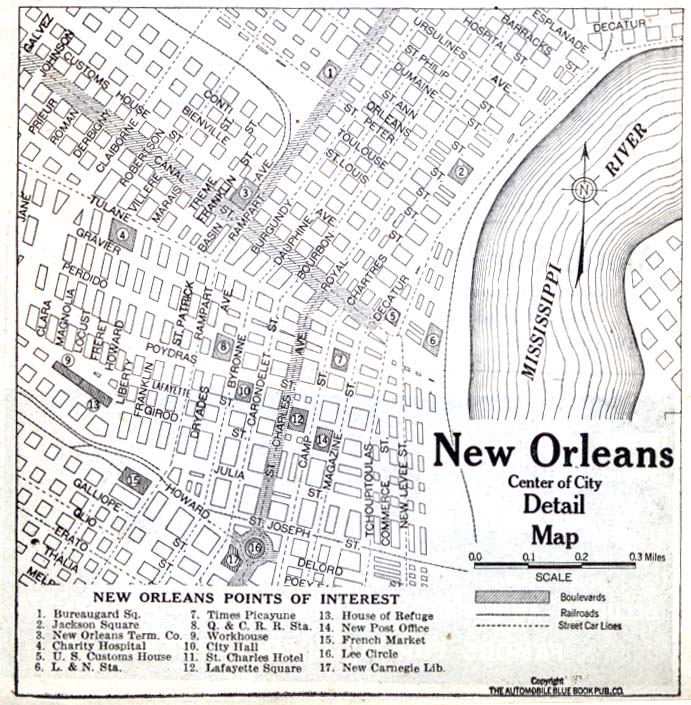

Geography

Map of Central NOLA

Districts

History

The Colonial Era

Before the founding of what would become known as the city of New Orleans, the area was inhabited by Native Americans for thousands of years. The Mississippian culture peoples built mounds and earthworks in the area. Later Native Americans created a portage between the headwaters of Bayou St. John (known to the natives as Bayouk Choupique) and the Mississippi River. The bayou flowed into Lake Pontchartrain. This became an important trade route. Archaeological evidence has shown settlement here dated back to at least 400 C.E.

French explorers, fur trappers and traders arrived in the area by the 1690s, some making settlements amid the Native American village of thatched huts along the bayou. By the end of the decade, the French made an encampment called "Port Bayou St. Jean" near the head of the bayou. They built a small fort "St. Jean" at the mouth of the bayou in 1701, used as a large Native American shell midden dating back to the Marksville culture. These early European settlements were then within the limits of the city of New Orleans, though predating its official date of founding.

New Orleans

New Orleans was founded in 1718 by the French as Nouvelle-Orléans, under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville. The site was selected because it was relatively high ground along the flood-prone banks of the lower Mississippi, and was adjacent to the trading route and portage between the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain via Bayou St. John. From its founding, the French intended it to be an important colonial city. The city was named in honor of the then Regent of France, Philip II, Duke of Orléans.

The priest-chronicler Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix described it in 1721 as a place of a hundred wretched hovels in a malarious wet thicket of willows and dwarf palmettos, infested by serpents and alligators; he seems to have been the first, however, to predict for it an imperial future. In 1722, Nouvelle-Orléans was made the capital of French Louisiana, replacing Biloxi in that role. In September of that year, a hurricane struck the city, blowing most of the structures down. After this, the administrators enforced the grid pattern dictated by Bienville but hitherto previously mostly ignored by the colonists. This grid is still seen today in the streets of the city's "French Quarter".

Much of the population in the early days was of the wildest and, in part, of the most undesirable character: deported galley slaves, trappers, gold-hunters and city scourings; and the governors' letters are full of complaints regarding the riffraff sent as soldiers as late as Kerlerec's administration from 1753 to 1763. In 1755 the British began the Great Expulsion which drove approximately 11,500 Acadians from the Nova Scotia area. Nearly a third drowned, several thousand stopped in other places, but many came to Louisiana to start over. Two lakes in the vicinity, Lake Pontchartrain and Maurepas, commemorate respectively Louis Phelypeaux, Count Pontchartrain, minister and chancellor of France, and Jean Frederic Phelypeaux, Count Maurepas, minister and secretary of state; a third is really a landlocked inlet of the sea, and its name (Lake Borgne) has reference to its incomplete or defective character.

Spanish Rule

In 1763 following Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War, the French colony west of the Mississippi River—plus New Orleans—was ceded to the Spanish Empire as a secret provision of the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau, confirmed the following year in the Treaty of Paris. This was to compensate Spain for the loss of Florida to the British, who also took the remainder of the formerly French territory east of the River.

No Spanish governor came to take control until 1766. French and German settlers, hoping to restore New Orleans to French control, forced the Spanish governor to flee to Spain in the bloodless Rebellion of 1768. A year later, the Spanish reasserted control, executing five ringleaders and sending five plotters to a prison in Cuba, and formally instituting Spanish law. Other members of the rebellion were forgiven as long as they pledged loyalty to Spain. Although a Spanish governor was in New Orleans, it was under the jurisdiction of the Spanish garrison in Cuba.

In the final third of the Spanish period, two massive fires burned the great majority of the city's buildings. The Great New Orleans Fire of 1788 destroyed 856 buildings in the city on Good Friday, March 21 of that year. In December 1794 another fire destroyed 212 buildings. After the fires, the city was rebuilt with bricks, replacing the simpler wooden buildings constructed in the early colonial period. Much of the 18th-century architecture still present in the French Quarter was built during this time, including three of the most impressive structures in New Orleans—St. Louis Cathedral, the Cabildo and the Presbytere. While the architecture from this period is commonly attributed to French influence, characteristics of the French Quarter, such as multi-storied buildings centered around inner courtyards, large arched doorways, and the use of decorative wrought-iron, were most ubiquitous in parts of Spain and the Spanish colonies. This influence may be attributed to the fact that the period of Spanish rule saw a great deal of immigration from all over the Atlantic, including Spain and the Canary Islands, and the Spanish colonies. In addition, it should be noted that while the architectural style of New Orleans, with its wrought iron balconies and full-height windows may remind one of Paris, many of New Orleans's oldest buildings actually predate the Haussman Projects that later renovated large areas of Paris in this same style.

In 1795 and 1796, the sugar processing industry was first put upon a firm basis. The last twenty years of the 18th century were especially characterized by the growth of commerce on the Mississippi, and the development of those international interests, commercial and political, of which New Orleans was the center. Within the city, the Carondelet Canal, connecting the back of the city along the river levee with Lake Pontchartrain via Bayou St. John, opened in 1794, which was a boost to commerce.

Through Pinckney's Treaty signed on October 27, 1795, Spain granted the United States "Right of Deposit" in New Orleans, allowing Americans to use the city's port facilities. In 1800 Spain and France signed the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso stipulating that Spain gave Louisiana back to France, though it had to remain under Spanish control as long as France wished to postpone the transfer of power.

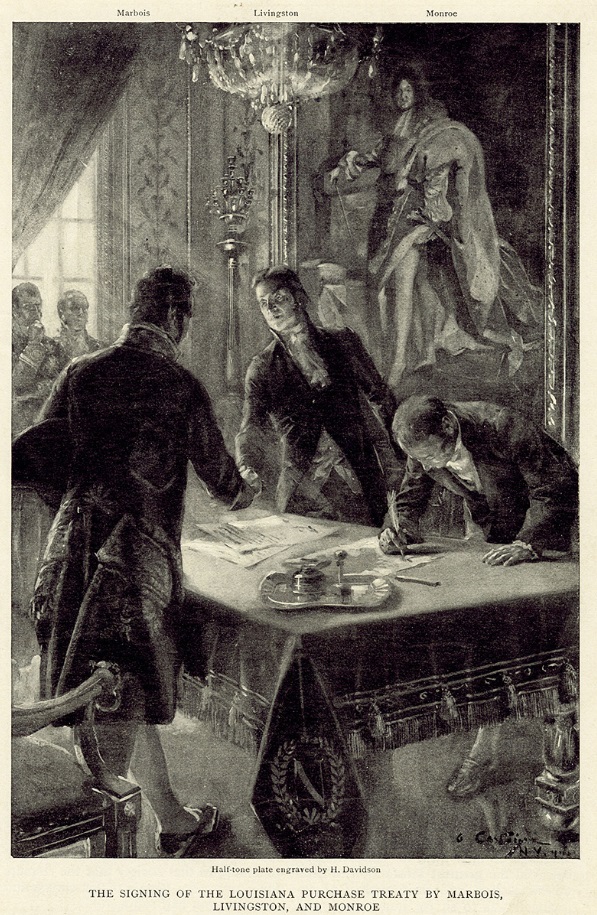

In April 1803, Napoleon sold Louisiana (which then included portions of more than a dozen present-day states) to the U.S. in the Louisiana Purchase. A French prefect, Pierre Clément de Laussat, who had arrived in New Orleans on March 23, 1803, formally took control of Louisiana for France on November 30, only to hand it over to the U.S. on December 20. In the meantime he created New Orleans' first city council.

The 19th Century

In 1805, a census showed a heterogeneous population of 8500. comprising 3551 whites, 1556 free blacks, and 3105 slaves. Observers at the time and historians since believe there was an undercount and the true population was about 10,000.

The Early Years

The next dozen years were marked by the beginnings of self-government in city and state; by the excitement attending the Aaron Burr conspiracy (in the course of which, in 1806–1807, General James Wilkinson practically put New Orleans under martial law); by the immigration from Cuba of French planters; and by the American War of 1812. From early days it was noted for its cosmopolitan polyglot population and mixture of cultures. The city grew rapidly, with influxes of Americans, African, French and Creole French (people of French descent born in the Americas) and Creoles of Color (people of mixed European and African ancestry), many of the latter two groups fleeing from the revolution in Haiti.

The Haitian Revolution of 1804 established the second republic in the Western Hemisphere and the first led by blacks. Haitian refugees, both white and free people of color (affranchis or gens de couleur libres), arrived in New Orleans, often bringing slaves with them. While Governor Claiborne and other officials wanted to keep out more free black men, French Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking population. As more refugees were allowed in Louisiana, Haitian émigrés who had gone to Cuba also arrived. Nearly 90 percent of the new immigrants settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites; 3,102 free persons of African descent; and 3,226 enslaved refugees to the city, doubling its French-speaking population. In addition, an 1809-1810 migration brought thousands of white francophone refugees from Saint-Domingue (deported by officials in Cuba in response to Bonapartist schemes in Spain).

The Slave Rebellions of 1811

The Haitian Revolution also increased ideas of resistance to the slaves of New Orleans. Early in 1811, hundreds of slaves revolted in what became known as the 1811 German Coast Uprising. The uprising occurred on the east bank of the Mississippi River in St. John the Baptist and St. Charles Parishes, Louisiana. While the slave insurgency was the largest in U.S. history, the rebels killed only two white men. Confrontations with militia and executions after so-called trials killed ninety-five black people.

Between 64 and 125 enslaved men marched from sugar plantations near present-day LaPlace on the German Coast toward the city of New Orleans. They collected more men along the way. Some accounts claimed a total of 200-500 slaves participated. During their two-day, twenty-mile march, the men burned five plantation houses (three completely), several sugar houses (small sugar mills), and crops. They were armed mostly with hand tools.

White men led by officials of the territory formed militia companies to hunt down and kill the insurgents, backed up by the United States Army under the command of Brigadier General Wade Hampton I, a slaveholder himself. Over the next two weeks, white planters and officials interrogated, sentenced, and carried out summary executions of an additional 44 insurgents who had been captured. The tribunals were held in three locations, in the two parishes involved and in Orleans Parish (New Orleans). Executions were by hanging, decapitation, or firing squad (St. Charles Parish). Whites displayed the bodies as a warning to intimidate slaves. The heads of some were put on pikes and displayed along the River Road and at the Place d'Armes in New Orleans.

The War of 1812

During the War of 1812, the British sent a large force to conquer the city, but they were defeated early in 1815 by Andrew Jackson's combined forces some miles downriver from the city at Chalmette's plantation, during the Battle of New Orleans. The American government managed to obtain early information of the enterprise and prepared to meet it with forces (regular, militia, and naval) under the command of Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson. Privateers led by Jean Lafitte were also recruited for the battle.

The British advance was made by way of Lake Borgne, and the troops landed at a fisherman's village on December 23, 1814, Major-General Sir Edward Pakenham taking command there two days later (Christmas). An immediate advance on the still insufficiently-prepared defenses of the Americans might have led to the capture of the city; but this was not attempted, and both sides limited themselves to relatively small skirmishes and a naval battle while awaiting reinforcements. At last in the early morning of January 8, 1815 (after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed but before the news had reached across the Atlantic), a direct attack was made on the now strongly-entrenched line of defenders at Chalmette, near the Mississippi River. It failed disastrously with a loss of 2,000 out of 9,000 British troops engaged, among the dead being Pakenham and Major-General Gibbs. The expedition was soon afterwards abandoned and the troops embarked, under the command of John Lambert. Another engagement followed: a ten-day artillery battle at Fort St. Philip on the lower Mississippi River. The British fleet set sail on January 18th and went on to capture Fort Bowyer at the entrance to Mobile Bay.

General Jackson had arrived in New Orleans in early December of 1814, having marched overland from Mobile in the Mississippi Territory. His final departure was not until mid-March of 1815. Martial law was maintained in the city throughout the period of three and a half months.

Antebellum New Orleans

The population of the city doubled in the 1830s with an influx of settlers. A few newcomers to the city were friends of the Marquis de Lafayette who had settled in the newly founded city of Tallahassee, Florida, but due to legalities had lost their deeds. One new settler who was not displaced but chose to move to New Orleans to practice law was Prince Achille Murat, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. According to historian Paul Lachance, “the addition of white immigrants to the white creole population enabled French-speakers to remain a majority of the white population until almost 1830. If a substantial proportion of free persons of color and slaves had not also spoken French, however, the Gallic community would have become a minority of the total population as early as 1820.” Large numbers of German and Irish immigrants began arriving at this time. The population of the city doubled in the 1830s and by 1840 New Orleans had become the wealthiest and third-most populous city in the nation.

By 1840, the city's population was approximately 102,000 and it was now the third-largest in the U.S, the largest city away from the Atlantic seaboard as well as the largest in the South.

The introduction of natural gas (about 1830); the building of the Pontchartrain Rail-Road (1830–31), one of the earliest in the United States; the introduction of the first steam-powered cotton press (1832), and the beginning of the public school system (1840) marked these years; foreign exports more than doubled in the period 1831–1833. In 1838 the commercially-important New Basin Canal opened a shipping route from the Lake to uptown New Orleans. Travelers in this decade have left pictures of the animation of the river trade more congested in those days of river boats, steamers, and ocean-sailing craft than today; of the institution of slavery, the quadroon balls, the medley of Latin tongues, the disorder and carousing of the river-men and adventurers that filled the city. Altogether there was much of the wildness of a frontier town, and a seemingly boundless promise of prosperity. The crisis of 1837, indeed, was severely felt, but did not greatly retard the city's advancement, which continued unchecked until the Civil War. In 1849 Baton Rouge replaced New Orleans as the capital of the state. In 1850 telegraphic communication was established with St. Louis and New York City; in 1851 the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern railway, the first railway outlet northward, later part of the Illinois Central, and in 1854 the western outlet, now the Southern Pacific, were begun.

In 1836 the city was divided into three municipalities: the first being the French Quarter and Faubourg Tremé, the second being Uptown (then meaning all settled areas upriver from Canal Street), and the third being Downtown (the rest of the city from Esplanade Avenue on, downriver). For two decades the three Municipalities were essentially governed as separate cities, with the office of Mayor of New Orleans having only a minor role in facilitating discussions between municipal governments.

The importance of New Orleans as a commercial center was reinforced when the United States Federal Government established a branch of the United States Mint there in 1838, along with two other Southern branch mints at Charlotte, North Carolina, and Dahlonega, Georgia. Although there was an existing coin shortage, the situation became much worse because in 1836 President Andrew Jackson had issued an executive order, called a specie circular, which demanded that all land transactions in the United States be conducted in cash, thus increasing the need for minted money. In contrast to the other two Southern branch mints, which only minted gold coins, the New Orleans Mint produced both gold and silver coinage, which perhaps marked it as the most important branch mint in the country.

The mint produced coins from 1838 until 1861, when Confederate forces occupied the building and used it briefly as their own coinage facility until it was recaptured by Union forces the following year.

On May 3, 1849, a Mississippi River levee breach upriver from the city (around modern River Ridge, Louisiana) created the worst flooding the city had ever seen. The flood, known as at Sauvé's Crevasse, left 12,000 people homeless. While New Orleans has experienced numerous floods large and small in its history, the flood of 1849 was of a more disastrous scale than any save the flooding after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. New Orleans has not experienced flooding from the Mississippi River since Sauvé's Crevasse, although it came dangerously close during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.

The Civil War

Early in the American Civil War New Orleans was captured by the Union without a battle in the city itself, and hence was spared the destruction suffered by many other cities of the American South. It retains a historical flavor with a wealth of 19th century structures far beyond the early colonial city boundaries of the French Quarter.

The political and commercial importance of New Orleans, as well as its strategic position, marked it out as the objective of a Union expedition soon after the opening of the Civil War. Elements of the Union Blockade fleet arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi on 27 May 1861. An effort to drive them off lead to the Battle of the Head of Passes on 12 October 1861. Captain D.G. Farragut and the Western Gulf squadron sailed for New Orleans in January 1862. The main defenses of the Mississippi consisted of the two permanent forts, Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip. On April 16, after elaborate reconnaissances, the Union fleet steamed up into position below the forts and opened fire two days later. Within days, the fleet had bypassed the forts in what was known as the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip. At noon on the 25th, Farragut anchored in front of New Orleans. Forts Jackson and St. Philip, isolated and continuously bombarded by Farragut's mortar boats, surrendered on the 28th, and soon afterwards the military portion of the expedition occupied the city resulting in the Capture of New Orleans.

The commander, General Benjamin Butler, subjected New Orleans to a rigorous martial law so tactlessly administered as greatly to intensify the hostility of South and North. Butler's administration did have benefits to the city, which was kept both orderly and due to his massive cleanup efforts unusually healthy by 19th century standards. Towards the end of the war General Nathaniel Banks held the command at New Orleans.

Era of Reconstruction

The city again served as capital of Louisiana from 1865 to 1880. Throughout the years of the Civil War and the Reconstruction period the history of the city is inseparable from that of the state. All the constitutional conventions were held here, the seat of government again was here (in 1864–1882) and New Orleans was the center of dispute and organization in the struggle between political and ethnic blocks for the control of government.

There was a major street riot of July 30, 1866, at the time of the meeting of the radical constitutional convention. Businessman Charles T. Howard began the Louisiana State Lottery Company in an arrangement which involved bribing state legislators and governors for permission to operate the highly lucrative outfit, as well as legal manipulations that at one point interfered with the passing of one version of the state constitution.

During Reconstruction, New Orleans was within the Fifth Military District of the United States. Louisiana was readmitted to the Union in 1868, and its Constitution of 1868 granted universal manhood suffrage. Both blacks and whites were elected to local and state offices. In 1872, then-lieutenant governor P.B.S. Pinchback succeeded Henry Clay Warmouth as governor of Louisiana, becoming the first non-white governor of a U.S. state, and the last African American to lead a U.S. state until Douglas Wilder's election in Virginia, 117 years later. In New Orleans, Reconstruction was marked by the Mechanics Institute race riot (1866). The city operated successfully a racially integrated public school system. Damage to levees and cities along the Mississippi River adversely affected southern crops and trade for the port city for some time, as the government tried to restore infrastructure. The nationwide Panic of 1873 also slowed economic recovery.

In the 1850s white Francophones had remained an intact and vibrant community, maintaining instruction in French in two of the city's four school districts. As the Creole elite feared, during the war, their world changed. In 1862, the Union general Ben Butler abolished French instruction in schools, and statewide measures in 1864 and 1868 further cemented the policy. By the end of the 19th century, French usage in the city had faded significantly.

New Orleans annexed the city of Algiers, Louisiana, across the Mississippi River, in 1870. The city also continued to expand upriver, annexing the town of Carrollton, Louisiana in 1874.

On September 14, 1874 armed forces led by the White League defeated the integrated Republican metropolitan police and their allies in pitched battle in the French Quarter and along Canal Street. The White League forced the temporary flight of the William P. Kellogg government, installing John McEnery as Governor of Louisiana. Kellogg and the Republican administration were reinstated in power three days later by United States troops. Early 20th century segregationists would celebrate the short-lived triumph of the White League as a victory for "white supremacy" and dubbed the conflict "The Battle of Liberty Place". A monument commemorating the event still stands near the foot of Canal Street, to the side of the Aquarium near the trolley tracks.

U.S. troops also blocked the White League Democrats in January 1875, after they had wrested from the Republicans the organization of the state legislature. Nevertheless, the revolution of 1874 is generally regarded as the independence day of Reconstruction, although not until President Hayes withdrew the troops in 1877 and the Packard government fell did the Democrats actually hold control of the state and city. The financial condition of the city when the whites gained control was very bad. The tax-rate had risen in 1873 to 3%. The city defaulted in 1874. On the interest of its bonded debt, it later refunded this ($22,000,000 in 1875) at a lower rate, to decrease the annual charge from $1,416,000 to $307,500.

The New Orleans Mint was reopened in 1879, minting mainly silver coinage, including the famed Morgan silver dollar from 1879 to 1904.

The city suffered flooding in 1882.

The city hosted the 1884 World's Fair, called the World Cotton Centennial. A financial failure, the event is notable as the beginnings of the city's tourist economy.

An electric lighting system was introduced to the city in 1886; limited use of electric lights in a few areas of town had preceded this by a few years.

1890s

On October 15, 1890, Chief-of-Police David C. Hennessy was shot, and reportedly his dying words informed a colleague that he was shot by "Dagos", an insulting term for Italians. On March 13, 1891, a group of Italian Americans on trial for the shooting were acquitted. However, a mob stormed the jail and lynched the accused and a number of other Italian-Americans. Local historians still debate whether some of those lynched were connected to the Mafia, but most agree that a number of innocent people were lynched during the Chief Hennessy Riot. The government of Italy protested, as some of those lynched were still Italian citizens, and the government of the U.S. eventually paid reparations to Italy.

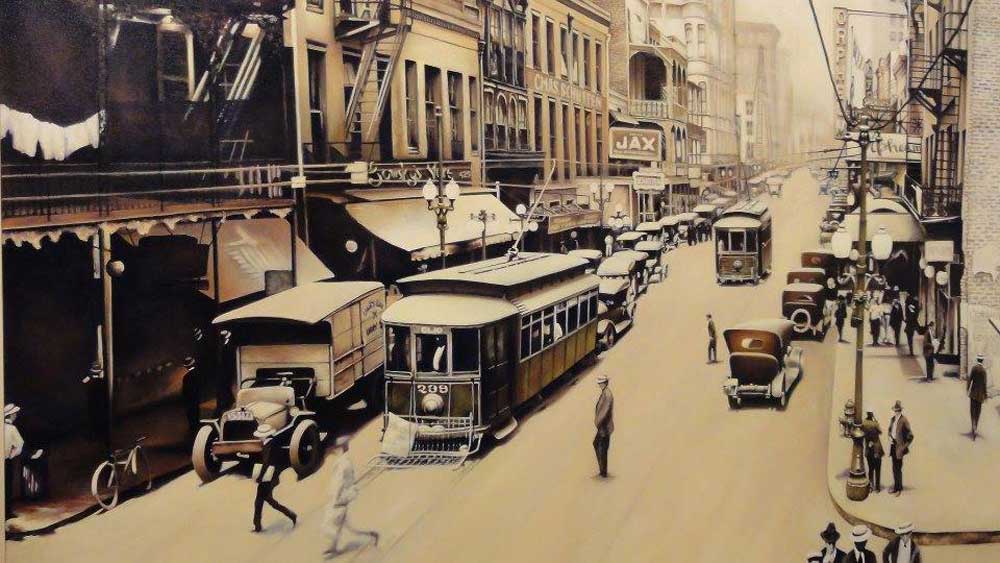

In the 1890s much of the city's public transportation system, hitherto relying on mule-drawn streetcars on most routes supplemented by a few steam locomotives on longer routes, was electrified.

With a large educated colored population that had long interacted with the white population, racial attitudes were comparatively liberal for the Deep South. Many in the city objected to the government of the State of Louisiana's attempt to enforce strict racial segregation, and hoped to overturn the law with a test case in 1892. The case found its way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896 as Plessy v. Ferguson. This resulted in upholding segregation, which would be enforced with ever-growing strictness for more than half a century.

In 1892, the New Orleans political machine, "the Ring," won a sweeping victory over the incumbent reformers. John Fitzpatrick, leader of the working class Irish, became mayor. In 1896 Mayor Fitzpatrick proposed combining existing library resources to create the city's first free public library, the Fisk Free and Public Library. This entity later became known as the New Orleans Public Library.

In the spring of 1896 Mayor Fitzpatrick, leader of the city's Bourbon Democratic organization, left office after a scandal-ridden administration, his chosen successor badly defeated by reform candidate Walter C. Flower. But Fitzpatrick and his associates quickly regrouped, organizing themselves on 29 December into the Choctaw Club, which soon received considerable patronage from Louisiana governor and Fitzpatrick ally Murphy Foster. Fitzpatrick, a power at the 1898 Louisiana Constitutional Convention, was instrumental in exempting immigrants from the new educational and property requirements designed to disenfranchise blacks. In 1899 he managed the successful mayoral campaign of Bourbon candidate Paul Capdevielle.

In 1897 the quasi-legal red light district called Storyville opened and soon became a famous attraction of the city.

The Robert Charles Riots occurred in July 1900. Well-armed African-American Robert Charles held off a group of policemen who came to arrest him for days, killing several of them. A White mob started a race riot, terrorizing and killing a number of African Americans unconnected with Charles. The riots were stopped when a group of White businessmen quickly printed and nailed up flyers saying that if the rioting continued they would start passing out firearms to the Colored population for their self-defense.

The Epidemics of 17th - 18th - 19th Centuries

The population of New Orleans and other settlements in south Louisiana suffered from epidemics of yellow fever, malaria, cholera, and smallpox, beginning in the late 18th century and periodically throughout the 19th century. Doctors did not understand how the diseases were transmitted; primitive sanitation and lack of a public water system contributed to public health problems, as did the highly transient population of sailors and immigrants. The city successfully suppressed a final outbreak of yellow fever in 1905. (See below, 20th century.)

Drainage in the Progressive Era

Much of the city is located below sea level between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, so the city is surrounded by levees.

Until the early 20th century, construction was largely limited to the slightly higher ground along old natural river levees and bayous; the largest section of this being near the Mississippi River front. This gave the 19th-century city the shape of a crescent along a bend of the Mississippi, the origin of the nickname The Crescent City. Between the developed higher ground near the Mississippi and the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, most of the area was wetlands only slightly above the level of Lake Pontchartrain and sea level. This area was commonly referred to as the "back swamp," or areas of cypress groves as "the back woods." While there had been some use of this land for cow pasture and agriculture, the land was subject to frequent flooding, making what would otherwise be valuable land on the edge of a growing city unsuitable for development. The levees protecting the city from high water events on the Mississippi and Lake compounded this problem, as they also kept rainwater in, which tended to concentrate in the lower areas. 19th century steam pumps were set up on canals to push the water out, but these early efforts proved inadequate to the task.

Following studies begun by the Drainage Advisory Board and the Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans in the 1890s, in the 1900s and 1910s engineer and inventor A. Baldwin Wood enacted his ambitious plan to drain the city, including large pumps of his own design that are still used when heavy rains hit the city. Wood's pumps and drainage allowed the city to expand greatly in area.

It only became clear decades later that the problem of subsidence had been underestimated. Much of the land in what had been the old back swamp has continued to slowly sink, and many of the neighborhoods developed after 1900 are now below sea level.

20th Century

In the early part of the 20th century the Francophone character of the city was still much in evidence, with one 1902 report describing "one-fourth of the population of the city speaks French in ordinary daily intercourse, while another two-fourths is able to understand the language perfectly." As late as 1945, one still encountered elderly Creole women who spoke no English. The last major French language newspaper in New Orleans, L’Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans, ceased publication on December 27, 1923, after ninety-six years; according to some sources Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Orleans continued until 1955.

In 1905, yellow fever was reported in the city, which had suffered under repeated epidemics of the disease in the previous century. As the role of mosquitoes in spreading the disease was newly understood, the city embarked on a massive campaign to drain, screen, or oil all cisterns and standing water (breeding ground for mosquitoes) in the city and educate the public on their vital role in preventing mosquitoes. The effort was a success and the disease was stopped before reaching epidemic proportions. President Theodore Roosevelt visited the city to demonstrate the safety of New Orleans. The city has had no cases of Yellow Fever since.

In 1909, the New Orleans Mint ceased coinage, with active coining equipment shipped to Philadelphia.

New Orleans was hit by major storms in the 1909 Atlantic hurricane season and again in the 1915 Atlantic hurricane season.

In 1917 the Department of the Navy ordered the Storyville District closed, over the opposition of Mayor Martin Behrman.

The Current Year is 1916

Population of the City

- -- (339,075): 1910 census +18.1%

- -- (387,219): 1920 census +14.2%

- -- (458,762): 1930 census +18.5%

- -- (494,537): 1940 census +7.8%

- -- (570,445): 1950 census +15.3%

- -- (627,525): 1960 census +10.0%

- -- (593,471): 1970 census −5.4%

- -- (557,515): 1980 census −6.1%

- -- (496,938): 1990 census −10.9%

- -- (484,674): 2000 census −2.5%

- -- (343,829): 2010 census −29.1%

- -- (384,320): 2014 census +11.8%

Economy

[[]]

Arenas

[[]]

Attractions

[[]]

- -- Bourbon Street

- -- French Market

- -- Storyville

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

- -- [[]]

Bars and Clubs

[[]]

- -- The Lamp Light -- A wild and raunchy strip club on Bourbon Street that occasionally closes its doors for Kindred only affairs.

- -- The Twilight Club -- A Kindred Gathering Place (Elysium)

Cemeteries

[[]]

- -- Cypress Grove Cemetery

- -- Gates of Prayer Cemetery No.1

- -- Gates of Prayer Cemetery No.2

- -- Greenwood Cemetery

- -- Hebrew Rest Cemetery

- -- Holt Cemetery

- -- Lafayette Cemetery No.1

- -- Masonic Cemetery

- -- St. Louis Cemetery No.1 -- The city's most famous cemetery

- -- St. Louis Cemetery No.2

- -- St. Louis Cemetery No.3

- -- St. Patrick's Cemetery No.1

- -- St. Patrick's Cemetery No.2

- -- St. Patrick's Cemetery No.3

- -- St. Roch Cemetery

City Government

Crime

[[]]

Citizens of 1920s New Orleans

- -- Lulu White -- Madame of Mahogany Hall (Storyville)

Culture

[[]]

http://www.nps.gov/jazz/learn/historyculture/jazz_history.htm

http://riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu/program/sobbin-blues-joe-oliver-new-orleans-trumpet-king

Current Events

[[]]

Festivals

[[]]

- -- Mardi Gras

Galleries

[[]]

Haunted Houses

[[]]

[[]]

[[]]

Holy Ground

[[]]

Hospitals

[[]]

Hotels & Hostels

[[]]

[[]]

[[]]

Landmarks

Monuments

[[]]

Museums

[[]]

Parks

[[]]

Periodicals

- -- The Times Picayune - 1920 (newspaper)

Private Residences

[[]]

Restaurants

[[]]

- -- Antoine's -- New Orleans' Oldest Restaurant

- -- Cafe du Monde

Schools

[[]]

Shops

[[]]

Theatres

[[]]

Transportation

The Vampires of Nawlins

"Take me in your arms"

"Forgetting all you couldn't do today"

"Black celebration"

"I'll drink to that"

"Black celebration"

"Tonight."

"Ain't No Rest for the Wicked" Cage the Elephant

-- Depeche Mode, "Black Celebration"

[[]] Assamites

[[]] Brujah

[[]] Cappadocians

[[]] Followers of Set

[[]] Gangrel

[[]] Lasombra

[[]] Malkavian

[[]] Nosferatu

[[]] Ravnos

[[]] Salubri

[[]] Toreador

[[]] Tzimisce

[[]] Ventrue

- -- Andre Foushon Prince

Bloodlines

Caitiff

Visitors

The Ghouls of the Big Easy

- -- Countess Willie Piazza -- Madam of the Willie Piazza House

The Magi of the Big Easy

Changing Breeds of the Bayous

The Wraiths of the NOLA Necropolis

Websites

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-w_itoTQi_U {U-tube Video}

http://photos.nola.com/1792/gallery/april_2012_photo_contest_new_orleans_at_night/index.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belle_Grove_Plantation_%28Iberville_Parish,_Louisiana%29

http://www.eatel.net/~meme/BelleGrove.html

http://www.neworleansonline.com/neworleans/attractions/cemeteries.html

http://www.neworleansonline.com/neworleans/nightlife/

http://www.stowawaymag.com/2011/09/voodoo-vampires-zombies/

http://www.pinterest.com/eyeofhorus/hoodoo-voodoo-vodou-nola/

http://www.storyvilledistrictnola.com/canal.html {historic pictures}

http://jazz-on-line.com/artists/Jelly_Roll_Morton.htm {MP3 jazz recordings from the period. Jelly Roll Morton is a famous man from the French Quarter}

http://americanhistory.si.edu/onthewater/exhibition/4_4.html {historic pictures}

http://www.frenchcreoles.com/frontpage.html

https://yesteryearsnews.wordpress.com/tag/thomas-jefferson/

http://www.hnoc.org/vcs/index.php