Kingdom of Germany

Introduction

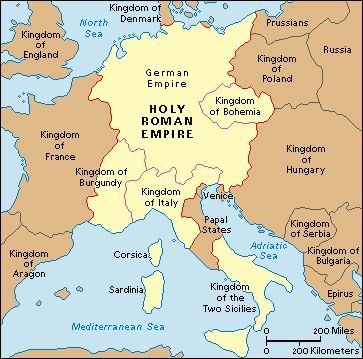

The Kingdom of Germany or German Kingdom (Latin: Regnum Teutonicum, "Teutonic Kingdom"; German: Deutsches Reich) developed out of the eastern half of the former Carolingian Empire. Like Anglo-Saxon England and medieval France, it began as "a conglomerate, an assemblage of a number of once separate and independent... gentes [peoples] and regna [kingdoms]." East Francia (Ostfrankenreich) was formed by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, and was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911, after which the kingship was elective. The initial electors were the rulers of the stem duchies, who generally chose one of their own. After 962, when Otto I was crowned emperor, the kingdom formed the bulk of the Holy Roman Empire, which also included Italy (after 951), Bohemia (after 1004) and Burgundy (after 1032).

The term rex teutonicorum ("king of the Germans") first came into use in the chancery of Pope Gregory VII during the Investiture Controversy (late 11th century), perhaps as a polemical tool against Emperor Henry IV. In the twelfth century, in order to stress the imperial and transnational character of their office, the emperors began to employ the title rex Romanorum (king of the Romans) on their election (by the prince-electors, seven German bishops and noblemen). Distinct titulature for Germany, Italy and Burgundy, which traditionally had their own courts, laws, and chanceries, gradually dropped from use. After the Imperial Reform and Reformation settlement, the German part of the Holy Roman Empire was divided into Reichskreise (imperial circles), which effectively defined Germany against imperial Italy and the Bohemian Kingdom. There are nevertheless relatively few references to a German realm and an instability in the term's use.

Terminology

The eastern division of the Treaty of Verdun was called the regnum Francorum Orientalium or Francia Orientalis: the Kingdom of the Eastern Franks or simply East Francia. It was the eastern half of the old Merovingian regnum Austrasiorum. The "east Franks" (or Austrasians) themselves were the people of Franconia, which had been settled by Franks. The other peoples of East Francia were Saxons, Frisians, Thuringii, and the like, referred to as Teutonici (or Germans) and sometimes as Franks as ethnic identities changed over the course of the ninth century.

An entry in the Annales Iuvavenses (or Salzburg Annals) for the year 919, roughly contemporary but surviving only in a twelfth-century copy, records that Baiuarii sponte se reddiderunt Arnolfo duci et regnare ei fecerunt in regno teutonicorum, i.e. that "Arnulf, Duke of the Bavarians, was elected to reign in the Kingdom of the Germans". Historians disagree on whether this text is what was written in the lost original; also on the wider issue whether the idea of the Kingdom as German, rather than Frankish, dates from the tenth or the eleventh century; but the idea of the kingdom as "German" is firmly established by the end of the eleventh century.

Beginning in the late eleventh century, during the Investiture Controversy, the Papal curia began to use the term regnum teutonicorum to refer to the realm of Henry IV in an effort to reduce him to the level of the other kings of Europe, while he himself began to use the title rex Romanorum or King of the Romans to emphasise his divine right to the imperium Romanum. This title was employed most frequently by the German kings themselves, though they did deign to employ "Teutonic" titles when it was diplomatic, such as Frederick Barbarossa's letter to the Pope referring to his receiving the coronam Theutonici regni (crown of the German kingdom). Foreign kings and ecclesiastics continued to refer to the regnum Alemanniae and règne or royaume d'Allemagne. The terms imperium/imperator or empire/emperor were often employed for the German kingdom and its rulers, which indicates a recognition of their imperial stature but combined with "Teutonic" and "Alemannic" references a denial of their Romanitas and universal rule. The term regnum Germaniae (literally "Kingdom of Germany") begins to appear even in German sources at the beginning of the fourteenth century.

Therefore, throughout the Middle Ages, the convention was that the (elected) king of Germany was also Emperor of the Romans. His title was royal (king of the Germans, or from 1237 king of the Romans) from his election to his coronation in Rome by the Pope; thereafter, he was emperor. After the death of Frederick II in 1250, the trend toward a "more clearly conceived German kingdom" found no real consolidation. The title of "king of the Romans" became less and less reserved for the emperor-elect but uncrowned in Rome; the emperor-elect was either known as German king or simply styled himself "imperator" (see the example of Louis IV below). The reign was dated to begin either on the day of election (Philip of Swabia, Rudolf of Habsburg) or the day of the coronation (Otto IV, Henry VII, Louis IV, Charles IV). The election day became the starting date permanently with Sigismund.

Ultimately, Maximilian I changed the style of the emperor in 1508, with papal approval: after his German coronation, his style was Dei gratia Romanorum imperator electus semper augustus. That is, he was "emperor elect": a term that did not imply that he was emperor-in-waiting or not yet fully emperor, but only that he was emperor by virtue of the election rather than papal coronation (by tradition, the style of rex Romanorum electus was retained between the election and the German coronation). At the same time, the custom of having the heir-apparent elected as king of the Romans in the emperor's lifetime resumed. For this reason, the title "king of the Romans" (rex Romanorum, sometimes "king of the Germans" or rex Teutonicorum) came to mean heir-apparent, the successor elected while the emperor was still alive.

The Archbishop of Mainz was ex officio arch-chancellor of Germany, as his colleagues the Archbishop of Cologne and Archbishop of Trier were, respectively, arch-chancellors of Italy and Burgundy. These titles continued in use until the end of the empire, but only the German chancery actually existed.