Difference between revisions of "Alexandria-- medieval"

(→Laibon (أبو الهول)) |

(→Whore Houses) |

||

| Line 512: | Line 512: | ||

== '''Whore Houses''' == | == '''Whore Houses''' == | ||

| + | :* Maki the guide | ||

| + | |||

| + | 40: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

---- | ---- | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 20:16, 27 September 2018

Contents

- 1 Quote (استشهد)

- 2 Appearance (مظهر)

- 3 Climate

- 4 Economy

- 5 History of Alexandria

- 6 Population

- 7 Cemeteries

- 8 Citizens of the City

- 9 Fortifications

- 10 Holy Ground

- 11 Inns

- 12 Law & Lawlessness

- 13 Maps

- 14 Monuments

- 15 Private Residences

- 16 Quarters of Alexandria

- 17 Supernaturals of Medieval Cairo

- 18 Taverns

- 19 Temples

- 20 Visitors

- 21 Whore Houses

- 22 The Damned Dead of the City of Memory (الموتى اللعينة لمدينة الذاكرة)

- 22.1 Kalisto's Ma'at

- 22.2 Introduction to the Unliving of Alexandria

- 22.3 Banu Haqim (بنو حقيم) -- Assamites of Alexandria

- 22.4 Banu min Allafayif (بانو من اللفائف) -- The Cold Brujah

- 22.5 Qabilat Al-Mawt (قبيلة الموت) -- The Cappadocians

- 22.6 Banu al as-Sa'idi (قبيلة من المصلين الثعبان) -- Followers of Set

- 22.7 Salubri

- 22.8 Qabilat Al-Khayal (قبيلة الخيال) -- Lasombra

- 22.9 Banu al - Hajji (سبط حجي) -- Muslim Nosferatu

- 22.10

- 22.11 Laibon (أبو الهول)

- 22.12 Toreador

- 22.13 Cainites of Lesser Blood

- 22.14 Shadows in Dust -- The Hidden Host

- 22.15 Ghouls and Future Cainites

- 23 Werewolves

- 24 Shemsu-Heru

- 25 Websites

Quote (استشهد)

You won’t find a new country, won’t find another shore.

This city will always pursue you.

You’ll walk the same streets, grow old

in the same neighborhoods, turn gray in these same houses.

You’ll always end up in this city. Don’t hope for things elsewhere:

there’s no ship for you, there’s no road.

Now that you’ve wasted your life here, in this small corner,

you’ve destroyed it everywhere in the world.

From Constantine P. Cavafy, "The City"

Appearance (مظهر)

Climate

Economy

History of Alexandria

Alexanders City

Alexandria is believed to have been founded by Alexander the Great in April 332 BC as Ἀλεξάνδρεια (Alexandria). Alexander's chief architect for the project was Dinocrates. Alexandria was intended to supersede Naucratis as a Hellenistic center in Egypt, and to be the link between Greece and the rich Nile valley. Although it has long been believed only a small village there, recent radiocarbon dating of seashell fragments and lead contamination show significant human activity at the location for two millennia preceding Alexandria's founding

Alexandria was the intellectual and cultural center of the ancient world for some time. The city and its museum attracted many of the greatest scholars, including Greeks, Jews and Syrians. The city was later plundered and lost its significance.

In the early Christian Church, the city was the center of the Patriarchate of Alexandria, which was one of the major centers of early Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire. In the modern world, the Coptic Orthodox Church and the Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria both lay claim to this ancient heritage.

Just east of Alexandria (where Abu Qir Bay is now), there was in ancient times marshland and several islands. As early as the 7th century BC, there existed important port cities of Canopus and Heracleion. The latter was recently rediscovered under water.

An Egyptian city, Rhakotis, already existed on the shore and later gave its name to Alexandria in the Egyptian language (Egyptian *Raˁ-Ḳāṭit, written rˁ-ḳṭy.t, 'That which is built up'). It continued to exist as the Egyptian quarter of the city. A few months after the foundation, Alexander left Egypt and never returned to his city. After Alexander's departure, his viceroy, Cleomenes, continued the expansion. Following a struggle with the other successors of Alexander, his general Ptolemy Lagides succeeded in bringing Alexander's body to Alexandria, though it was eventually lost after being separated from its burial site there.

Although Cleomenes was mainly in charge of overseeing Alexandria's continuous development, the Heptastadion and the mainland quarters seem to have been primarily Ptolemaic work. Inheriting the trade of ruined Tyre and becoming the center of the new commerce between Europe and the Arabian and Indian East, the city grew in less than a generation to be larger than Carthage. In a century, Alexandria had become the largest city in the world and, for some centuries more, was second only to Rome. It became Egypt's main Greek city, with Greek people from diverse backgrounds.

Alexandria was not only a center of Hellenism, but was also home to the largest urban Jewish community in the world. The Septuagint, a Greek version of the Tanakh, was produced there. The early Ptolemies kept it in order and fostered the development of its museum into the leading Hellenistic center of learning (Library of Alexandria), but were careful to maintain the distinction of its population's three largest ethnicities: Greek, Jewish, and Egyptian. By the time of Augustus, the city walls encompassed an area of 5.34 sq.kilometres,and the total population in Roman times was around 500-600,000.

In AD 115, large parts of Alexandria were destroyed during the Kitos War, which gave Hadrian and his architect, Decriannus, an opportunity to rebuild it. In 215, the emperor Caracalla visited the city and, because of some insulting satires that the inhabitants had directed at him, abruptly commanded his troops to put to death all youths capable of bearing arms. On 21 July 365, Alexandria was devastated by a tsunami (365 Crete earthquake),[10] an event annually commemorated years later as a "day of horror."

Muhammad's era

The Islamic prophet Muhammad's first interaction with the people of Egypt occurred in 628, during the Expedition of Zaid ibn Haritha (Hisma). He sent Hatib bin Abi Baltaeh with a letter to the king of Egypt (in reality Emperor Heraclius) and Alexandria called Muqawqis[12][13] In the letter Muhammad said: "I invite you to accept Islam, Allah the sublime, shall reward you doubly. But if you refuse to do so, you will bear the burden of the transgression of all the Copts". During this expedition one of Muhammad's envoys Dihyah bin Khalifa Kalbi was attacked, Muhammad sent Zayd ibn Haritha to help him. Dihya approached the Banu Dubayb (a tribe which converted to Islam and had good relations with Muslims) for help. When the news reached Muhammad, he immediately dispatched Zayd ibn Haritha with 500 men to battle. The Muslim army fought with Banu Judham, killed several of them (inflicting heavy casualties), including their chief, Al-Hunayd ibn Arid and his son, and captured 1000 camels, 5000 of their cattle and 100 women and boys. The new chief of the Banu Judham who had embraced Islam appealed to Muhammad to release his fellow tribesmen, and Muhammad released them.

Islamic era

In 619, Alexandria fell to the Sassanid Persians. Although the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius recovered it in 629, in 641 the Arabs under the general 'Amr ibn al-'As captured it during the Muslim conquest of Egypt, after a siege that lasted 14 months.

A Brief History of Egypt

The history of Egypt has been long and rich, due to the flow of the Nile river, with its fertile banks and delta. Its rich history also comes from its native inhabitants and outside influence. Much of Egypt's ancient history was a mystery until the secrets of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs were deciphered with the discovery and help of the Rosetta Stone. The Great Pyramid of Giza is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still standing. The Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the other Seven Wonders, is gone. The Library of Alexandria was the only one of its kind for centuries.

Human settlement in Egypt dates back to at least 40,000 BC with Aterian tool manufacturing. Ancient Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh of the First Dynasty, Narmer. Predominately native Egyptian rule lasted until the conquering of Egypt by the Achaemenid Persian Empire in the 6th century BC.

In 332 BC, Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great conquered Egypt as he toppled the Achaemenids and established the Hellenistic Ptolemaic Kingdom, whose first ruler was one of Alexander's former generals, Ptolemy I Soter. The Ptolemies had to fight native rebellions and were involved in foreign and civil wars that led to the decline of the kingdom and its final annexation by Rome. The death of Cleopatra ended the nominal independence of Egypt resulting in Egypt becoming one of the provinces of the Roman Empire.

Roman rule in Egypt (including Byzantine) lasted from 30 BC to 641 AD, with a brief Sassanid Persian interlude between 619-629, known as Sasanian Egypt. After the Islamic conquest of Egypt, parts of Egypt became provinces of successive Caliphates and other Muslim dynasties: Rashidun Caliphate (632-661), Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), Abbasid Caliphate (750-909), Fatimid Caliphate (909-1171), Ayyubid Sultanate (1171–1260), and the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt (1250-1517).

The History of Alexandria

Just east of Alexandria in ancient times (where now is Abu Qir Bay) there was marshland and several islands. As early as 7th century BC, there existed important port cities of Canopus and Heracleion. The latter was recently rediscovered under water. Part of Canopus is still on the shore above water, and had been studied by archaeologist the longest. There was also the town of Menouthis. The Nile Delta had long been politically significant as the point of entry for anyone wishing to trade with Egypt.

An Egyptian city or town, Rhakotis, existed on the shore where Alexandria is now. Behind it were five villages scattered along the strip between Lake Mareotis and the sea, according to the Romance of Alexander.

Alexandria was founded by Alexander the Great in 331 BC (the exact date is disputed) as Ἀλεξάνδρεια (Aleksándreia). Alexander's chief architect for the project was Dinocrates. Ancient accounts are extremely numerous and varied, and much influenced by subsequent developments. One of the more sober descriptions, given by the historian Arrian, tells how Alexander undertook to lay out the city's general plan, but lacking chalk or other means, resorted to sketching it out with grain. A number of more fanciful foundation myths are found in the Alexander Romance and were picked up by medieval historians.

A few months after the foundation, Alexander left Egypt for the East and never returned to his city. After Alexander departed, his viceroy, Cleomenes, continued the expansion of the city.

In a struggle with the other successors of Alexander, his general, Ptolemy (later Ptolemy I of Egypt) succeeded in bringing Alexander's body to Alexandria. Alexander's tomb became a famous tourist destination for ancient travelers (including Julius Caesar). With the symbols of the tomb and the Lighthouse, the Ptolemies promoted the legend of Alexandria as an element of their legitimacy to rule.

Alexandria was intended to supersede Naucratis as a Hellenistic center in Egypt, and to be the link between Greece and the rich Nile Valley. If such a city was to be on the Egyptian coast, there was only one possible site, behind the screen of the Pharos island and removed from the silt thrown out by the Nile, just west of the westernmost "Canopic" mouth of the river. At the same time, the city could enjoy a fresh water supply by means of a canal from the Nile. The site also offered unique protection against invading armies: the vast Libyan Desert to the west and the Nile Delta to the east.

Though Cleomenoes was mainly in charge of seeing to Alexandria's continuous development, the Heptastadion (causeway to Pharos Island) and the main-land quarters seem to have been mainly Ptolemaic work. Demographic details of how Alexandria rose quickly to its great size remain unknown.

Inheriting the trade of ruined Tyre and becoming the center of the new commerce between Europe and the Arabian and Indian East, the city grew in less than a generation to be larger than Carthage. In a century, Alexandria had become the largest city in the world and for some centuries more, was second only to Rome. It became the main Greek city of Egypt, with an extraordinary mix of Greeks from many cities and backgrounds. Nominally a free Hellenistic city, Alexandria retained its senate of Roman times and the judicial functions of that body were restored by Septimius Severus after temporary abolition by Augustus. Construction

Monumental buildings were erected in Alexandria through the third century BC. The Heptastadion connected Pharos with the city and the Lighthouse of Alexandria followed soon after, as did the Serapeum, all under Ptolemy I. The Museion was built under Ptolemy II; the Serapeum expanded by Ptolemy III Euergetes; and mausolea for Alexander and the Ptolemies built under Ptolemy IV.

The Ptolemies fostered the development of the Library of Alexandria and associated Musaeum into a renowned center for Hellenistic learning.

Luminaries associated with the Museum included the geometry and number-theorist Euclid; the astronomer Hipparchus; and Eratosthenes, known for calculating the Earth's circumference and for his algorithm for finding prime numbers, who became head librarian.

Strabo lists Alexandria, with Tarsus and Athens, among the learned cities of the world, observing also that Alexandria both admits foreign scholars and sends its natives abroad for further education.[8] Ethnic divisions

The early Ptolemies were careful to maintain the distinction of its population's three largest ethnicities: Greek, Jewish, and Egyptian. (At first, Egyptians were probably the plurality of residents, while the Jewish community remained small. Slavery, a normal institution in Greece, was likely present but details about its extent and about the identity of slaves are unknown.) Alexandrian Greeks placed an emphasis on Hellenistic culture, in part to exclude and subjugate non-Greeks.

The law in Alexandria was based on Greek—especially Attic—law. There were two institutions in Alexandria devoted to the preservation and study of Greek culture, which helped to exclude non-Greeks. In literature, non-Greek texts entered the library only once they had been translated into Greek. Notably, there were few references to Egypt or native Egyptians in Alexandrian poetry; one of the few references to native Egyptians presents them as "muggers." There were ostentatious religious processions in the streets that displayed the wealth and power of the Ptolemies, but also celebrated and affirmed Greekness. These processions were used to shout Greek superiority over any non-Greeks that were watching, thereby widening the divide between cultures.[12]

From this division arose much of the later turbulence, which began to manifest itself under the rule of Ptolemy Philopater (221–204 BC). The reign of Ptolemy VIII Physcon from 144–116 BC was marked by purges and civil warfare (including the expulsion of intellectuals such as Apollodorus of Athens), as well as intrigues associated with the king's wives and sons.

Alexandria was also home to the largest Jewish community in the ancient world. The Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (the Torah and other writings), was produced there. Jews occupied two of the city's five quarters and worshiped at synagogues.

Roman era

The city passed formally under Roman jurisdiction in 80 BC, according to the will of Ptolemy Alexander but only after it had been under Roman influence for more than a hundred years. Julius Caesar dallied with Cleopatra in Alexandria in 47 BC and was besieged in the city by Cleopatra's brother and rival. His example was followed by Mark Antony, for whose favor the city paid dearly to Octavian. Following Antony's defeat in Alexandria at the Battle of Actium, Octavian took Egypt as personal property of the emperor, appointing a prefect who reported personally to him rather than to the Roman Senate[citation needed]. While in Alexandria, Octavian took time to visit Alexander's tomb and inspected the late king's remains. On being offered a viewing into the tombs of the pharaohs, he refused, saying, "I came to see a king, not a collection of corpses."

From the time of annexation and onwards, Alexandria seemed to have regained its old prosperity, commanding, as it did, an important granary of Rome. This was one of the chief reasons that induced Octavian to place it directly under imperial power.

Jewish–Greek ethnic tensions in the era of Roman administration led to riots in AD 38 and again in 66. Buildings were burned during the Kitos War (Tumultus Iudaicus) of AD 115, giving Hadrian and his architect, Decriannus, an opportunity to rebuild.

In 215 AD the emperor Caracalla visited the city and, because of some insulting satires that the inhabitants had directed at him, abruptly commanded his troops to put to death all youths capable of bearing arms. This brutal order seems to have been carried out even beyond the letter, for a general massacre ensued. According to historian Cassius Dio, over 20,000 people were killed.

In the 3rd century AD, Alexander's tomb was closed to the public, and now its location has been forgotten.

Late Roman and Byzantine period

Even as its main historical importance had sprung from pagan learning, Alexandria now acquired new importance as a center of Christian theology and church government. There Arianism came to prominence and there also Athanasius, opposed both Arianism and pagan reaction against Christianity, experiencing success against both and continuing the Patriarch of Alexandria's major influence on Christianity into the next two centuries.

Persecution of Christians under Diocletian (beginning in AD 284) marks the beginning of the Era of Martyrs in the Coptic calendar.

As native influences began to reassert themselves in the Nile valley, Alexandria gradually became an alien city, more and more detached from Egypt and losing much of its commerce as the peace of the empire broke up during the 3rd century, followed by a fast decline in population and splendor.

In 365, a tsunami caused by an earthquake in Crete hit Alexandria.

In the late 4th century, persecution of pagans by Christians had reached new levels of intensity. Temples and statues were destroyed throughout the Roman empire: pagan rituals became forbidden under punishment of death, and libraries were closed. In 391, Emperor Theodosius I ordered the destruction of all pagan temples, and the Patriarch Theophilus complied with his request. The Serapeum of the Great Library was destroyed, possibly effecting the final destruction of the Library of Alexandria. The neoplatonist philosopher Hypatia was publicly murdered by a Christian mob.

The Brucheum and Jewish quarters were desolate in the 5th century, and the central monuments, the Soma and Museum, fell into ruin. On the mainland, life seemed to have centered in the vicinity of the Serapeum and Caesareum, both which became Christian churches. The Pharos and Heptastadium quarters, however, remained populous and were left intact.

Recent archaeology at Kom El Deka (heap of rubble or ballast) has found the Roman quarter of Alexandria beneath a layer of graves from the Muslim era. The remains found at this site, which are dated circa the fourth to seventh centuries AD, include workshops, storefronts, houses, a theater, a public bath, and lecture halls, as well as Coptic frescoes. The baths and theater were built in the fourth century and the smaller buildings constructed around them, suggesting a sort of urban renewal occurring in the wake of Diocletian.

Arab rule

In 616, the city was taken by Khosrau II, King of Persia. Although the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius recovered it a few years later, in 641 the Arabs, under the general Amr ibn al-As during the Muslim conquest of Egypt, captured it decisively after a siege that lasted fourteen months. The city received no aid from Constantinople during that time; Heraclius was dead and the new Emperor Constans II was barely twelve years old. In 645 a Byzantine fleet recaptured the city, but it fell for good the following year. Thus ended a period of 975 years of the Greco-Roman control over the city. Nearly two centuries later, between the years 814 and 827, Alexandria came under the control of pirates of Andalusia (Spain today), later to return to Arab hands.[20] In the year 828, the alleged body of Mark the Evangelist was stolen by Venetian merchants, which led to the Basilica of Saint Mark and there depoistaram the body. Years later, the city suffered many earthquakes during the years 956, 1303 and then in 1323. After a long decline, Alexandria emerged as major metropolis at the time of the Crusades and lived a flourishing period due to trade with agreements with the Aragonese, Genoese and Venetians who distributed the products arrived from the East through the Red Sea. It formed an emirate of the Ayyubid Empire, where Saladin's elder brother Turan Shah was granted a sinecure to keep him from the front lines of the crusades.

Current Events

History

After the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 641, Rashidun commander Amr ibn al-As established Fustat just north of Coptic Cairo. At Caliph Umar's request, the Egyptian capital was moved from Alexandria to the new city on the eastern side of the Nile.

The reach of the Umayyads was extensive, stretching from western Spain all the way to eastern China. However, they were overthrown by the Abbasids, who moved the capital of the Umayyad empire itself to Baghdad. In Egypt, this shift in power involved moving control from the Umayyad city of al-Fustat slightly north to the Abbasid city of al-‘Askar. Its full name was مدينة العسكري Madinatu l-‘Askari "City of Cantonments" or "City of Sections". Intended primarily as a city large enough to house an army, it was laid out in a grid pattern that could be easily subdivided into separate sections for various groups such as merchants and officers.

The peak of the Abbasid dynasty occurred during the reign of Harun al Rashid, along with increased taxes on the Egyptians, who rose up in a peasant revolt in 832 during the time of Caliph al-Ma'mun. Local Egyptian governors gained increasing autonomy, and in 870, governor Ahmad ibn Tulun declared Egypt's independence (though still nominally under the rule of the Abbasid Caliph). As a symbol of this independence, in 868 ibn Tulun founded yet another capital, al-Qatta'i, slightly further north of al-‘Askar. The capital remained there until 905, until the city was destroyed, and the administrative capital of Egypt then returned to al-Fusṭāṭ.

Al-Fusṭāṭ itself was destroyed by a vizier-ordered fire that burned from 1168 to 1169, at which time the capital moved to nearly al-Qāhirah (Cairo), where it has remained to this day. Cairo's bounds grew to eventually encompass the three earlier capitals of al-Fusṭāṭ, al-Qatta'i and al-‘Askar, the remnants of which can today be seen in "Old Cairo" in the southern part of the city.

Al-Qata'i

Al-Qaṭāʾi (Arabic: القطائـع) was the short-lived Tulunid capital of Egypt, founded by Ahmad ibn Tulun in the year 868 CE. Al-Qata'i was located immediately to the northeast of the previous capital, al-Askar, which in turn was adjacent to the settlement of Fustat. All three settlements were later incorporated into the city of al-Qahira (Cairo), founded by the Fatimids in 969 CE. The city was razed in the early 10th century CE, and the only surviving structure is the Mosque of Ibn Tulun.

History

Each of the new cities was founded with a change in the governance of the Middle East: Fustat was the first Arab settlement in Egypt, founded by Amr ibn al-A'as in 642 following the Arab conquest of Egypt. Al-Askar succeeded Fustat as capital of Egypt after the move of the caliphate from the Umayyad dynasty in Damascus to the Abbasids in Baghdad around 750 CE.

Al-Qata'i ("The Quarters") was established by Ahmad ibn Tulun when he was sent to Egypt by the Abbasid caliph to assume the governorship in 868 CE. Ibn Tulun arrived with a large military force that was too large to be housed in al-Askar. The city was founded on the Gabal Yashkhur, a hill to the northeast of the existing settlements that was said to have been the landing point for Noah's Ark after the Deluge, according to a local legend.

Al-Qata'i was modeled to some degree after Samarra in Iraq, where Ibn Tulun had undergone military training. Samarra was a city of sections, each designated for a particular social stratum or subgroup. Likewise, certain areas of al-Qata'i were allocated to officers, civil servants, specific military corps, Greeks, guards, policemen, camel drivers, and slaves. The new city was not intended to replace Fustat, which was a thriving market town, but rather to serve as an expansion of it. Many of the government officials continued to reside in Fustat.

The focal point of al-Qata'i was the large ceremonial mosque, named for Ibn Tulun, which is still the largest mosque in terms of area in Cairo. Among other architectural features, the mosque is noted for its use of pointed arches two centuries before they appeared in European architecture. The historian al-Maqrizi reported that a new mosque had to be built because the existing ceremonial mosque in Fustat, named for Amr ibn al-A'as, could not accommodate Ibn Tulun's personal regiment at the Friday prayer. Ibn Tulun's palace, the Dar al-Imara ("House of the Emir") was built adjacent to the mosque and a private door allowed the governor direct access to the pulpit, or minbar. The palace faced a large parade ground and park, featuring gardens and a hippodrome.

Ibn Tulun also commissioned the construction of an aqueduct to bring water to the existing town, and a maristan (hospital), the first such public institution in Egypt, founded in 873. An endowment was established to fund both in perpetuity. Ibn Tulun secured a significant income for the capital through various military campaigns, and many taxes were abolished during his rule. Following Ibn Tulun's death in 884, his son Khumarawayh focused much of his attention on enlarging the already lavish palace structures. He also built several irrigation canals and a sewage system in al-Qata'i.

In 905, Egypt was reoccupied by the Abbasids, and, in retaliation for the Tulunids long military campaigns against the caliphate, the city was plundered and razed, leaving only the mosque standing. Administration was then transferred back to al-Askar, which had become geographically indistinct from Fustat.

After the founding of al-Qahira in 969, Fustat/al-Askar and al-Qahira eventually grew together, building over the remains of the Tulunid capital and incorporating the Mosque of Ibn Tulun into the new urban landscape.

Places of Interest

Population

- Annual Census, 1100 A.D.:

Bazaars

Cemeteries

The Cities of the Dead

Citizens of the City

Clergy

Craftsmen

Criminals

- Turnus Myllisandus (Low end illegal money changer)

Guides

Moneylender

Nobles

Slaves

Wizards (hermetic)

Fortifications

Holy Ground

Churches

Convents

Mosques

Inns

Law & Lawlessness

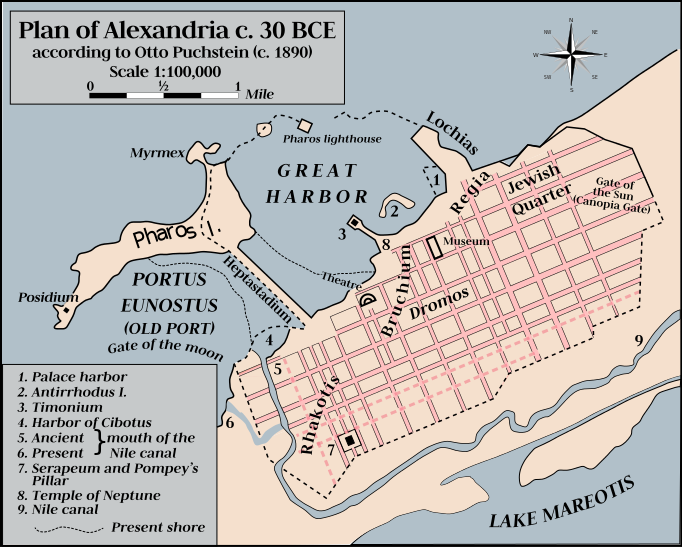

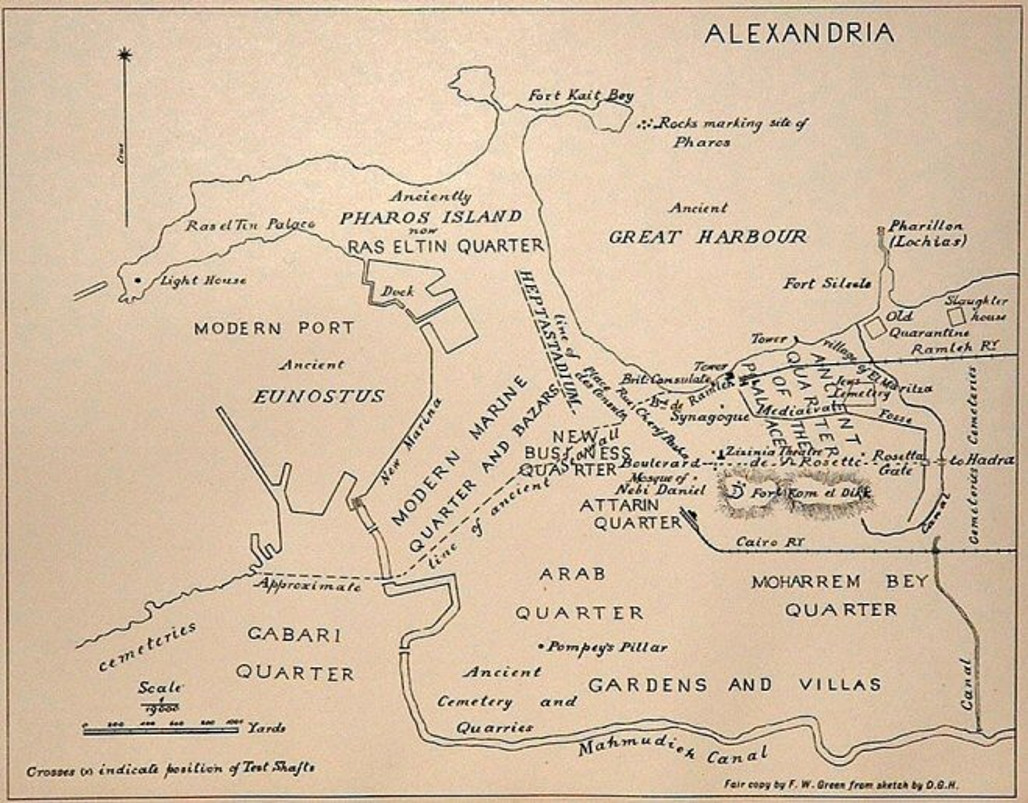

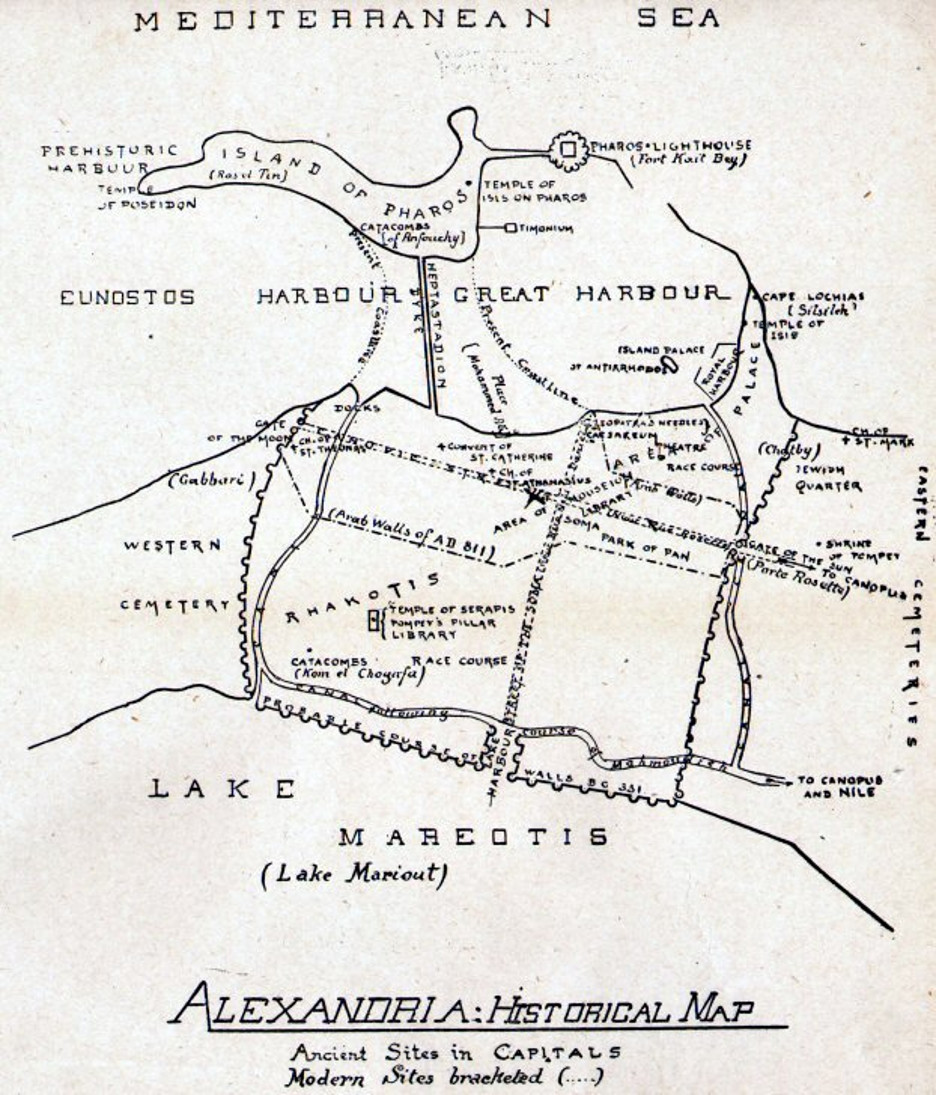

Maps

Monuments

Arches (Triumphal)

Bridges

Columns

Pompey's Pillar (عمود السواري)

Pompey's Pillar is a Roman triumphal column in Alexandria, Egypt, the largest of its type constructed outside the imperial capitals of Rome and Constantinople, located at the Serapeum of Alexandria. The only known free-standing column in Roman Egypt which was not composed of drums, it is one of the largest ancient monoliths and one of the largest monolithic columns ever erected.

Construction

The monolithic column shaft measures 20.46 m in height with a diameter of 2.71 m at its base. The weight of the single piece of red Aswan granite is estimated at 285 tonnes. The column is 26.85 m high including its base and capital. Other authors give slightly deviating dimensions.

Erroneously dated to the time of Pompey, the Corinthian column was actually built in 297 AD, commemorating the victory of Roman emperor Diocletian over an Alexandrian revolt.

Anecdotes

Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta visited Alexandria in 1326 AD. He describes the pillar and recounts the tale of an archer who shot an arrow tied to a string over the column. This enabled him to pull a rope tied to the string over the pillar and secure it on the other side in order to climb over to the top of the pillar.

In early 1803, British commander John Shortland of HMS Pandour flew a kite over Pompey's Pillar. This enabled him to get ropes over it, and then a rope ladder. On February 2, he and John White, Pandour's Master, climbed it. When they got to the top they displayed the Union Jack, drank a toast to King George III, and gave three cheers. Four days later they climbed the pillar again, erected a staff, fixed a weather vane, ate a beef steak, and again toasted the king.

Fountains

Gates

Lighthouse of Alexandria

Introduction

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, sometimes called the Pharos of Alexandria was a lighthouse built by the Ptolemaic Kingdom, during the reign Ptolemy II Philadelphus (280–247 BC) which has been estimated to be 100 metres (330 ft) in overall height. One of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, for many centuries it was one of the tallest man-made structures in the world. Badly damaged by three earthquakes between AD 956 and 1323, it then became an abandoned ruin. It was the third longest surviving ancient wonder (after the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus and the extant Great Pyramid of Giza), surviving in part until 1480, when the last of its remnant stones were used to build the Citadel of Qaitbay on the site. In 1994, French archaeologists discovered some remains of the lighthouse on the floor of Alexandria's Eastern Harbour. In 2016 the Ministry of State of Antiquities in Egypt had plans to turn submerged ruins of ancient Alexandria, including those of the Pharos, into an underwater museum.

Origin

Pharos was a small island located on the western edge of the Nile Delta. In 332 BC Alexander the Great founded the city of Alexandria on an isthmus opposite Pharos. Alexandria and Pharos were later connected by a mole spanning more than 1200 metres (.75 mi), which was called the Heptastadion ("seven stadia"—a stadium was a Greek unit of length measuring approximately 180 m). The east side of the mole became the Great Harbour, now an open bay; on the west side lay the port of Eunostos, with its inner basin Kibotos now vastly enlarged to form the modern harbor. Today's city development lying between the present Grand Square and the modern Ras el-Tin quarter is built on the silt which gradually widened and obliterated this mole, and the Ras el-Tin promontory represents all that is left of the island of Pharos, the site of the lighthouse at its eastern point having been weathered away by the sea.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lighthouse_of_Alexandria)

Mausolea

Statues

Tombs

Private Residences

Quarters of Alexandria

Brucheum

The Royal or Greek quarter, forming the most magnificent portion of the city. In Roman times Brucheum was enlarged by the addition of an official quarter, making four regions in all. The city was laid out as a grid of parallel streets, each of which had an attendant subterranean canal;

Drommos

The Jewish quarter

Forming the northeast portion of the city;

Rhakotis

The old city of Rhakotis that had been absorbed into Alexandria was occupied chiefly by Egyptians.

Two main streets, lined with colonnades and said to have been each about 60 meters (200 ft) wide, intersected in the center of the city, close to the point where the Sema (or Soma) of Alexander (his Mausoleum) rose. This point is very near the present mosque of Nebi Daniel; and the line of the great East–West "Canopic" street, only slightly diverged from that of the modern Boulevard de Rosette (now Sharia Fouad). Traces of its pavement and canal have been found near the Rosetta Gate, but remnants of streets and canals were exposed in 1899 by German excavators outside the east fortifications, which lie well within the area of the ancient city.

Alexandria consisted originally of little more than the island of Pharos, which was joined to the mainland by a 1,260-metre-long (4,130 ft) mole and called the Heptastadion ("seven stadia"—a stadium was a Greek unit of length measuring approximately 180 metres or 590 feet). The end of this abutted on the land at the head of the present Grand Square, where the "Moon Gate" rose. All that now lies between that point and the modern "Ras al-Tin" quarter is built on the silt which gradually widened and obliterated this mole. The Ras al-Tin quarter represents all that is left of the island of Pharos, the site of the actual lighthouse having been weathered away by the sea. On the east of the mole was the Great Harbor, now an open bay; on the west lay the port of Eunostos, with its inner basin Kibotos, now vastly enlarged to form the modern harbor.

Supernaturals of Medieval Cairo

- Mages of Alexandria

- Fae of the Desert

Taverns

- Nossiques Brothel

Temples

Serapeum of Alexandria

Quote

"Serapeum, quod licet minuatur exilitate verborum, atriis tamen columnariis amplissimis et spirantibus signorum figmentis et reliqua operum multitudine ita est exornatum, ut post Capitolium, quo se venerabilis Roma in aeternum attollit, nihil orbis terrarum ambitiosius cernat." -- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, XXII, 16

{"The Serapeum, splendid to a point that words would only diminish its beauty, has such spacious rooms flanked by columns, filled with such life-like statues and a multitude of other works of such art, that nothing, except the Capitolium, which attests to Rome's venerable eternity, can be considered as ambitious in the whole world."}

Introduction

"A serapeum is a temple or other religious institution dedicated to the syncretic Greco-Egyptian deity Serapis, who combined aspects of Osiris and Apis in a humanized form that was accepted by the Ptolemaic Greeks of Alexandria. There were several such religious centers, each of which was a serapeion (Greek: Σεραπεῖον) or, in its Latinized form, a serapeum."

The Serapeum of Alexandria in the Ptolemaic Kingdom was an ancient Greek temple built by Ptolemy III Euergetes (reigned 246–222 BCE) and dedicated to Serapis, who was made the protector of Alexandria. There are also signs of Harpocrates. It has been referred to as the daughter of the Library of Alexandria. The site has been heavily plundered.

History

The site is located on a rocky plateau, overlooking land and sea. By all detailed accounts, the Serapeum was the largest and most magnificent of all temples in the Greek quarter of Alexandria. Besides the image of the god, the temple precinct housed an offshoot collection of the great Library of Alexandria. The geographer Strabo tells that this stood in the west of the city. Nothing now remains above ground, except the enormous Pompey's Pillar. According to Rowe and Rees 1956, a Aphthonius, the Greek rhetorician of Antioch visited Serapeum about 315 AD.

The Serapeum of Alexandria was closed in July of 325 AD, likely on the orders of Constantine. Then in 391 AD religious riots broke out, according to Wace:

"The Serapeum was the last stronghold of the pagans who fortified themselves in the temple and its enclosure. The sanctuary was stormed by the Christians. The pagans were driven out, the temple was sacked, and its contents were destroyed. In this struggle the Library presumably perished also."

The Serapeum in Alexandria was destroyed by a Christian mob or Roman soldiers in 391 (although the date is debated).[4] Several conflicting accounts for the context of the destruction of the Serapeum exist.

According to early Christian sources, bishop Pope Theophilus of Alexandria was the Nicene patriarch when the decrees of emperor Theodosius I forbade public observances of any rites but Christian. Theodosius I had gradually made (year 389) the sacred feasts of other faiths into workdays, forbidden public sacrifices, closed temples, and colluded in acts of local violence by Christians against major cult sites. The decree promulgated in 391 that "no one is to go to the sanctuaries, [or] walk through the temples" resulted in the abandonment of many temples throughout the Empire, which set the stage for widespread practice of converting or replacing these sites with Christian churches.

In Alexandria, Bishop Theophilus obtained legal authority over one such forcibly abandoned temple of Dionysus (or, in another version of the story, a Mithraeum), which he intended to turn into a church. During the renovations, the contents of subterranean spaces ("secret caverns" in the Christian sources) were uncovered and profaned, which allegedly incited crowds of non-Christians to seek revenge. The Christians retaliated, as Theophilus withdrew, causing the pagans to retreat into the Serapeum, still the most imposing of the city's remaining sanctuaries, and to barricade themselves inside, taking captured Christians with them. These sources report that the captives were forced to offer sacrifices to the banned deities, and that those who refused were tortured (their shins broken) and ultimately cast into caves that had been built for blood sacrifices. The trapped pagans plundered the Serapeum.

A letter was sent by Theodosius to Theophilus, asking him to grant the offending pagans pardon and calling for the destruction of all pagan images, suggesting that these were at the origin of the commotion. Consequently, the Serapeum was levelled by Roman soldiers and monks called in from the desert, as were the buildings dedicated to the Egyptian god Canopus. The wave of destruction of non-Christian idols spread throughout Egypt in the following weeks, as documented by a marginal illustration on papyrus from a world chronicle written in Alexandria in the early 5th century, which shows Theophilus in triumph; the cult image of Serapis, crowned with the modius, is visible within the temple at the bottom.

An alternate account of the incident is found in writings by Eunapius, the pagan historian of later Neoplatonism. Here, an unprovoked Christian mob successfully used military-like tactics to destroy the Serapeum and steal anything that may have survived the attack. According to Eunapius, the remains of criminals and slaves, who had been occupying the Serapeum at the time of the attack, were appropriated by non-Christians, placed in (surviving) pagan temples, and venerated as martyrs.

Whichever the cause, the destruction of the Serapeum, described by Christian writers Tyrannius Rufinus and Sozomen, was but the most spectacular of such conflicts, according to Peter Brown. Several other ancient and modern authors, instead, have interpreted the destruction of the Serapeum in Alexandria as representative of the triumph of Christianity and an example of the attitude of the Christians towards pagans. However, Peter Brown frames it against a long-term backdrop of frequent mob violence in the city, where the Greek and Jewish quarters had fought during four hundred years, since the 1st century BCE. Also, Eusebius mentions street-fighting in Alexandria between Christians and non-Christians, occurring as early as 249. There is evidence that non-Christians had taken part in citywide struggles both for and against Athanasius of Alexandria in 341 and 356. Similar accounts are found in the writings of Socrates of Constantinople. R. McMullan further reports that, in 363 (almost 30 years earlier), George of Cappadocia was killed for his repeated acts of pointed outrage, insult, and pillage of the most sacred treasures of the city.

Whatever the prior events, the Serapeum of Alexandria was not rebuilt.

After the destruction a monastery was established, a church was built for St. John the Baptist, known as Angelium or Evangelium. However, the church fell to ruins around 600 AD, restored by patriarch Isaac (681-684 AD), and finally destroyed in the 10th Century. More recently a Bab Sidra Moslem cemetery was located at the site.

Excavations

Architecture has been traced to an early Ptolemaic and a second Roman period. The excavations at the site of the column of Diocletian in 1944 yielded the foundation deposits of the Serapeion. These are two sets of ten plaques, one each of gold, silver, bronze, Egyptian faience, sun-dried Nile mud, and five of opaque glass. The inscription that Ptolemy III Euergetes built the Serapeion, in Greek and Egyptian, marks all plaques; evidence suggests that Parmeniskos (Parmenion) was assigned as architect. The foundation deposits of a temple dedicated to Harpocrates from the reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator were also found within the enclosure walls. Signs point to a first destruction during the Kitos War in 116 AD. It has been suggested it was then rebuild under Hadrian. This is supported with the 1895 find of a black diorite statue, representing Serapis in his Apis bull incarnation with the sun disk between his horns; an inscription dates it to the reign of Hadrian (117-138). It has also been suggested that there was worship of the goddess of health, marriage, and wisdom Isis. Subterranean galleries beneath the temple were most probably the site of the mysteries of Serapis. Granite columns suggest a Roman rebuilding and widening of the Alexandrine Serapeum in AD 181–217. Excavations recovered 58 bronze coins, and 3 silver coins, with dates up to 211.[11] The torso of a marble statue of Mithras was found in 1905/6.

Statues

According to fragments, there were statues of the twelve gods. Mimaut mentioned in the 19th century, nine standing statues holding rolls, which would coincident with the nine goddesses of the arts, reportedly present at the Library of Alexandria. Eleven statues were found at Saqqara. A review of "Les Statues Ptolémaïques du Sarapieion de Memphis" noted they were probably sculpted in the 3rd century with limestone and stucco, some standing others sitting. Rowe and Rees 1956 suggested that both scenes in the Serapeum of Alexandria and Saqqara, share a similar theme, such as with Plato's Academy mosaic, with Saqqara figures attributed to: "(1) Pindare, (2) Démétrios de Phalère, (3) x (?), (4) Orphée (?) aux oiseaux, (5) Hésiode, (6) Homère, (7) x (?), (8) Protagoras, (9) Thalès, (10) Héraclite, (11) Platon, (12) Aristote (?)."

Visitors

Whore Houses

- Maki the guide

40:

The Damned Dead of the City of Memory (الموتى اللعينة لمدينة الذاكرة)

The Pharoah of Alexandria runs the city with an iron fist which is an interesting departure for the Third Eye Clan. Kalisto has been the the Pharoah for nearly five hundred years. Kalisto has been known to send Ufuoma, Job and his henchmen out to bring in those who violate her laws. Her rules have made it possible for Islam to become a dominant religion here, even though she acknowledges the older Gods of Egypt.

Kalisto seeks the protection of the past in the city, and therefore has made rules that will keep the Library and it's remaining works safe. The catacombs are protected zones, with a desire by the Pharoah to not bring the undead to the attention of the Church.

Kalisto's Ma'at

Ma'at is good and its worth is lasting. It has not been disturbed since the day of its creator, whereas he who transgresses its ordinances is punished. It lies as a path in front even of him who knows nothing. Wrongdoing has never yet brought its venture to port. It is true that evil may gain wealth but the strength of truth is that it lasts;

In addition to the Ma'at of Cain, thou shall not violate my Ma'at on pain of trial before my throne.

- Thou shall not take works from the Library, those who steal our heritage will be hunted and left for the sun.

- Thou shall not offend the Followers of the Christ Messiah. The church should stay ignorant of the children of Lilith and Cain.

- Molest not the Desert Wolves, Our pact is sacrosanct. Any who bring strife with the Garou will pay a heavy debt.

Introduction to the Unliving of Alexandria

Banu Haqim (بنو حقيم) -- Assamites of Alexandria

The Lost Tribe, forerunners of the Black Hand, operated out of Alexandria for a time.

- Dastur Anosh

- El-Ghazzawi

- Farouk Adebayo

- Zakchaios Ayodele

- Dastur Anosh

Banu min Allafayif (بانو من اللفائف) -- The Cold Brujah

Qabilat Al-Mawt (قبيلة الموت) -- The Cappadocians

- Seppo Temitope

- Tychon Naaji

Banu al as-Sa'idi (قبيلة من المصلين الثعبان) -- Followers of Set

Court of Miracles

The Followers of Set maintain a temple in Alexandria, the Court of Miracles.

Unlike the other major temples to Set, Egypt's northernmost court was established only after a foreign presence had already staked a claim. Located in Alexandria, the Court of Miracles was founded in the 2nd century B.C. by a mysterious all-female cabal of Setites. Its founding members seem to have enjoyed peculiar and often romantic relations with Alexandria's rulers of the era -- the Ptolemies -- and they are rumored to have somehow been involved in the arrival of their progenitor, Alexander the Great.

Shortly after its founding as a true Temple of Set, the Alexandrian court was called upon to join the war against the Osirian League. However to the shock of the other Setites, it refused. During this time, all manner of rumors began to float down the Nile toward the other, more traditional courts to the south. Indeed, the vast majority of the clan "gossip" of the time pertained to the new, unorthodox cult of Setites in charge of the capital city's temple.

The city was also the birthplace of the Cult of Typhon Trismegistus, and their abandoned temple (the Typhoneum) still houses ancient lore.

- Vasco Kamau

- Ugo Gama

- Amaal the Dancer

Salubri

- Kalisto Kore Pharaoh of Alexandria

- Ufuoma

- Job Al-Amin

Qabilat Al-Khayal (قبيلة الخيال) -- Lasombra

- Eniola Pini

- Kwadwo Rana

Banu al - Hajji (سبط حجي) -- Muslim Nosferatu

- Antonello

- Zola Aqil

- Tawfiq

- Antonello

Ghouls

Laibon (أبو الهول)

Toreador

- Arhmazdi Mercury

Cainites of Lesser Blood

Shadows in Dust -- The Hidden Host

Ghouls and Future Cainites

Werewolves

The Black Furies established a caern near Alexandria called the Sept of the Bloodied Stair early in the city's history, some time prior to 30 BCE.

Shemsu-Heru

In 132 CE, Horus commanded the Shemsu-Heru to disperse through the world and fight Apophis each in their own way; Alexandria became the central port and hub of their activities. The Viziers kept their council here until the Sixth Great Maelstrom.

Websites